(Press-News.org) Like all metals, silver, copper, and gold are conductors. Electrons flow across them, carrying heat and electricity. While gold is a good conductor under any conditions, some materials have the property of behaving like metal conductors only if temperatures are high enough; at low temperatures, they act like insulators and do not do a good job of carrying electricity. In other words, these unusual materials go from acting like a chunk of gold to acting like a piece of wood as temperatures are lowered. Physicists have developed theories to explain this so-called metal-insulator transition, but the mechanisms behind the transitions are not always clear.

"In some cases, it is not easy to predict whether a material is a metal or an insulator," explains Caltech visiting associate Yejun Feng of the Okinawa Institute for Science and Technology Graduate University. "Metals are always good conductors no matter what, but some other so-called apparent metals are insulators for reasons that are not well understood." Feng has puzzled over this question for at least five years; others on his team, such as collaborator David Mandrus at the University of Tennessee, have thought about the problem for more than two decades.

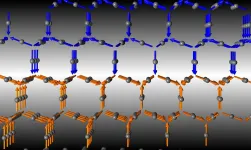

Now, a new study from Feng and colleagues, published in Nature Communications, offers the cleanest experimental proof yet of a metal-insulator transition theory proposed 70 years ago by physicist John Slater. According to that theory, magnetism, which results when the so-called "spins" of electrons in a material are organized in an orderly fashion, can solely drive the metal-insulator transition; in other previous experiments, changes in the lattice structure of a material or electron interactions based on their charges have been deemed responsible.

"This is a problem that goes back to a theory introduced in 1951, but until now it has been very hard to find an experimental system that actually demonstrates the spin-spin interactions as the driving force because of confounding factors," explains co-author Thomas Rosenbaum, a professor of physics at Caltech who is also the Institute's president and the Sonja and William Davidow Presidential Chair.

"Slater proposed that, as the temperature is lowered, an ordered magnetic state would prevent electrons from flowing through the material," Rosenbaum explains. "Although his idea is theoretically sound, it turns out that for the vast majority of materials, the way that electrons interact with each other electronically has a much stronger effect than the magnetic interactions, which made the task of proving the Slater mechanism challenging."

The research will help answer fundamental questions about how different materials behave, and may also have applications in technology, for example in the field of spintronics, in which the spins of electrons would form the basis of electrical devices instead of the electron charges as is routine now. "Fundamental questions about metal and insulators will be relevant in the upcoming technological revolution," says Feng.

Interacting Neighbors

Typically, when something is a good conductor, such as a metal, the electrons can zip around largely unimpeded. Conversely, with insulators, the electrons get stuck and cannot travel freely. The situation is comparable to communities of people, explains Feng. If you think of materials as communities and electrons as members of the households, then "insulators are communities with people who don't want their neighbors to visit because it makes them feel uncomfortable." Conductive metals, however, represent "close-knit communities, like in a college dorm, where neighbors visit each other freely and frequently," he says.

Likewise, Feng uses this metaphor to explain what happens when some metals become insulators as temperatures drop. "It's like winter time, in that people--or the electrons--stay home and don't go out and interact."

In the 1940s, physicist Sir Nevill Francis Mott figured out how some metals can become insulators. His theory, which garnered the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physics, described how "certain metals can become insulators when the electronic density decreases by separating the atoms from each other in some convenient way," according to the Nobel Prize press release. In this case, the repulsion between the electrons is behind the transition.

In 1951, Slater proposed an alternate mechanism based on spin-spin interactions, but this idea has been hard to prove experimentally because the other processes of the metal-insulator transition, including those proposed by Mott, can swamp the Slater mechanism, making it hard to isolate.

Challenges of Real Materials

In the new study, the researchers were able at last to experimentally demonstrate the Slater mechanism using a compound that has been studied since 1974, called pyrochlore oxide or Cd2Os2O7. This compound is not affected by other metal-insulator transition mechanisms. However, within this material, the Slater mechanism is overshadowed by an unforeseen experimental challenge, namely the presence of "domain walls" that divide the material into sections.

"The domain walls are like the highways or bigger roads between communities," says Feng. In pyrochlore oxide, the domain walls are conductive, even though the bulk of the material is insulating. Although the domain walls started out as an experimental challenge, they turned out to be essential to the team's development of a new measurement procedure and technique to prove the Slater mechanism.

"Previous efforts to prove the Slater metal-insulator transition theory did not account for the fact that the domain walls were masking the magnetism-driven effects," says Yishu Wang (PhD '18), a co-author at the Johns Hopkins University who has continuously worked on this study since her graduate work at Caltech. "By isolating the domain walls from the bulk of the insulating materials, we were able to develop a more complete understanding of the Slater mechanism." Wang had previously worked with Patrick Lee, a visiting professor at Caltech from MIT, to lay the basic understanding of conductive domain walls using symmetry arguments, which describe how and if electrons in materials respond to changes in the direction of a magnetic field.

"By challenging the conventional assumptions about how electrical conductivity measurements are made in magnetic materials through fundamental symmetry arguments, we have developed new tools to probe spintronic devices, many of which depend on transport across domain walls," says Rosenbaum.

"We developed a methodology to set apart the domain-wall influence, and only then could the Slater mechanism be revealed," says Feng. "It's a bit like discovering a diamond in the rough."

INFORMATION:

The paper, titled, "A continuous metal-insulator transition driven by spin correlations," was funded by the Okinawa Institute, with subsidy funding from the Cabinet Office, Government of Japan; the National Science Foundation; the Air Force Office of Scientific Research; and the U.S. Department of Energy. Other authors include Daniel M. Silevitch of Caltech and Scott E. Cooper of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. Mandrus is also affiliated with the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

There's a lot of interest right now in how different microbiomes--like the one made up of all the bacteria in our guts--could be harnessed to boost human health and cure disease. But Daniel Segrè has set his sights on a much more ambitious vision for how the microbiome could be manipulated for good: "To help sustain our planet, not just our own health."

Segrè, director of the END ...

A new drug reduced tumor size in patients who have lung cancer patients with a specific, disease-causing change in the gene KRAS, a study found.

The results of the CODEBREAK 100 phase 2 clinical trial were presented June 4, 2021, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine. The efficacy and safety of the drug sotorasib, developed by Amgen Inc., was tested in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring a specific change, or mutation, in the DNA code for KRAS.

The KRAS mutant protein targeted in the study was p.G12C, in which a glycine building ...

Washington, DC--A team led by Carnegie's Thomas Shiell and Timothy Strobel developed a new method for synthesizing a novel crystalline form of silicon with a hexagonal structure that could potentially be used to create next-generation electronic and energy devices with enhanced properties that exceed those of the "normal" cubic form of silicon used today.

Their work is published in Physical Review Letters.

Silicon plays an outsized role in human life. It is the second most abundant element in the Earth's crust. When mixed with other elements, it is essential for many construction and infrastructure projects. And in pure elemental form, it ...

A study of more than 1,000 demographically representative participants found that about 22 percent of Americans self-identify as anti-vaxxers, and tend to embrace the label as a form of social identity.

According to the study by researchers including Texas A&M University School of Public Health assistant professor Timothy Callaghan, 8 percent of this group "always" self-identify this way, with 14 percent "sometimes" identifying as part of the anti-vaccine movement. The results were published in the journal Politics, Groups, and Identities.

"We found these results both surprising and concerning," Callaghan said. "The fact that 22 percent of Americans at least sometimes identify as anti-vaxxers was much higher than expected and demonstrates ...

Most Americans should get screened for colorectal cancer beginning at age 45 instead of age 50, according to new recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which includes UVA Health's Li Li, MD, PhD, MPH. This recommendation applies to Americans without symptoms who do not have a history of colorectal polyps or a personal or family health history of genetic disorders that increase the risk of colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the third-leading cause of cancer death in America, according to the Task Force, and an increasing number of cases are being diagnosed in younger Americans. The Task Force notes that colorectal cancer diagnoses among Americans ages 40 to 49 increased by almost 15% from 2000-02 to 2014-16. Black ...

While previous research early in the pandemic suggested that vitamin D cuts the risk of contracting COVID-19, a new study from McGill University finds there is no genetic evidence that the vitamin works as a protective measure against the coronavirus.

"Vitamin D supplementation as a public health measure to improve outcomes is not supported by this study. Most importantly, our results suggest that investment in other therapeutic or preventative avenues should be prioritized for COVID-19 randomized clinical trials," say the authors.

To assess the relationship between vitamin D levels and COVID-19 ...

Tuberculosis (TB) is a deadly infection that occurs in every part of the world. The standard treatment for TB, a six-month multidrug regimen, has not changed in more than 40 years. Patients can find it difficult to complete the lengthy regimen, making it more likely that treatment resistance will develop.

A research team led by a Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) investigator reports in the May 6 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine that a four-month treatment regimen using rifapentine is effective for treating TB. Shortening the treatment duration is an important step toward increased patient adherence.

In 2019 alone, 1.4 ...

As meat-eating continues to increase around the world, food scientists are focusing on ways to create healthier, better-tasting and more sustainable plant-based protein products that mimic meat, fish, milk, cheese and eggs.

It's no simple task, says renowned food scientist David Julian McClements, University of Massachusetts Amherst Distinguished Professor and lead author of a paper in the new Nature journal, Science of Food, that explores the topic.

"With Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods and other products coming on the market, there's a huge interest in plant-based foods for ...

Physicists in Israel have created a quantum interferometer on an atom chip. This device can be used to explore the fundamentals of quantum theory by studying the interference pattern between two beams of atoms. University of Groningen physicist, Anupam Mazumdar, describes how the device could be adapted to use mesoscopic particles instead of atoms. This modification would allow for expanded applications. A description of the device, and theoretical considerations concerning its application by Mazumdar, were published on 28 May in the journal Science Advances.

The device which scientists from the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev created is a so-called Stern Gerlach Interferometer, which was first proposed one hundred years ago by German physicists Otto Stern and Walter ...

Researchers in Lund, Copenhagen and Norwich have shown that harmful mutations present in the DNA play an important - yet neglected - role in the conservation and translocation programs of threatened species.

"Many species are threatened by extinction, both locally and globally. For example, we have lost about ten vertebrate species in Sweden in the last century. However, all these species occur elsewhere in Europe, which means that they could be reintroduced into Sweden. Our computer simulations show how we could theoretically maximize the success of such reestablishments", says Bengt Hansson, biologist at Lund University.

In a new study published in Science, the researchers investigated which individuals might be most suited for translocation ...