(Press-News.org) For decades, physicians and dieticians have urged people to limit their intake of high fat foods, citing links to poor health outcomes and some of the leading causes of death in the U.S., such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, dietary components high in saturated fats such as red meat are thought to be risk factors for colon cancer. Diet is thought to strongly influence the risk of colorectal cancer, and changes in food habits might reduce up to 70% of this cancer burden.

Other known epidemiological risk factors are family history, inflammatory bowel disease, smoking and type-2 diabetes.

But out of all the risk factors that elevate colon cancer risk, diet is the one environmental and lifestyle factor that may be the easiest to control ---simply by changing people's behavior and eating habits----if we knew the exact connections.

"There's epidemiological evidence for a strong link between obesity and increased tumor risk," said School of Life Sciences assistant professor Miyeko Mana. "And in the intestine, the stem cells are the likely cell of origin for cancer. So, what is that connection? Well, diet is something that feeds into that cycle of obesity and colorectal cancer."

Now, a new ASU study led by Mana and her team has shown in greater detail than ever before of how high fat diets can trigger a molecular cascade of events that leads to intestinal and colon cancer. The study was published in the journal Cell Reports.

Tales from the crypts

As foods are broken down and make their way through the gut, they interact with intestinal stem cells (ISC) that lie along the inside surfaces of the gut. These ISCs reside in a series of regularly folded valleys of the gut, called crypts.

ISCs are thought to be the gateway that coordinates intestinal tumor formation when they adapt to high-fat diets, and elevate cancer risk. Within the ISCs are high-fat sensor molecules that sense and react to high-fat diets levels in the cells.

"We were following up on mechanisms that might be required for stem cells to adapt to the high fat diet ---and that's where we came across the PPARs," said Mana. These peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (or PPARs) trigger a cellular program that elevates cancer risk, but the exact mechanisms were unclear because there are multiple types of PPARs, and complexities in teasing out their roles.

"There is a family of 3 PPARs, named delta, alpha and gamma. At first, I thought just PPAR delta was involved, but in order to see if that gene is really responsible for the phenotype, you have to remove it."

Mana's team was able to explore and unmask the role of individual PPAR delta and alpha using a mouse model that controlled their activity in the cell. In her team's study, mice were given a long-term high fat or normal diet, and the activity of each PPAR was carefully monitored to study the effects on cancer risk.

In their knockout study, they first removed the PPAR delta gene.

"But when we removed it from the intestine, we still observed the phenotype. So, we wondered if maybe another PPAR was compensating and that's where we thought about PPAR alpha. Both of those (PPAR delta and PPAR alpha) appear to be required for this high fat diet phenotype within the stem cells."

This was frustrating to Mana because she knew right away that developing a potential therapeutic to offset the PPARs just became a much taller task.

"When you think about this therapeutically, if you are incorporating a lot of fat into your diet and you want to reduce your risk of colon cancer, targeting two different factors is more challenging then if you are targeting just one."

Looking farther downriver

To further tease out the genetic complexity, Mana next turned her attention downstream of the PPARs.

From their studies, and using new tools of the trade, they were able to slowly tease out the details---down to the level of doing molecular sequencing from individual cells from different areas of the small intestine and colon, mass spectrometry to measure the amounts of different metabolites, and radiolabeled isotopes of fuel sources to measure the carbon flow.

Their first big clue came from the metabolic analysis. The high fat diet found in the ISC crypt cells they isolated increased the metabolism of fats, while at the same time, decreasing the breakdown of sugars.

"So, we looked more downstream at what these two factors (PPARs) may target, and that was this mitochondrial protein, Cpt1a," said Mana. "This is required for the import of long chain fatty acids (LCFAs) into mitochondria for use. The LCFAs are part of the high fat diet."

And when they performed the mouse knockout study of Cpt1a, they found they could stop tumor formation in its tracks. The loss of Cpt1a prevented both the expansion and proliferation of the ISCs in the crypts.

"If you remove Cpt1a, you are spared this high fat diet phenotype in the intestinal stem cells," said Mana. "So, you lower your risk of tumorigenesis at this point."

A new model emerges

From their data, Mana' team could trace the development of cancer, from diet all the way to tumor formation.

First, fats are broken down to free fatty acids. The free fatty acids then stimulate sensors such as the PPARs and turn on genes that can break down the fatty acids.

Next, the surplus free fatty acids are transported to the mitochondria, which can burn them up by oxidation to make more energy to feed the stem cells, which multiply, grow and regenerate gut tissue. But when the ISCs numbers are expanded, there is a greater likelihood that mutations can occur---just from random mutations and sheer numbers of cells---that lead to colon cancer.

"The idea is that this larger pool of cells remain in the intestine and accumulate mutations, and that means they can be a source of mutated cells leading to transformation and tumor initiation," said Mana. "We do think that is a likely possibility when there are conditions that expand your stem cell pool."

Mana's group also found that feeding a high fat diet dramatically accelerated mortality in this model compared with the control condition, by accelerating tumorigenesis.

"The levels of these fats that you can get through your diet are going to impact your stem cells, probably in a fairly direct way," said Mana. "I think one of the surprising things we are finding in our studies is that fatty acids can have such a direct effect. But you can remove these PPARs, you can remove CPT1a, and the intestine is fine."

New hopes

With the new evidence from the study, the hope is to one day apply their work to human colon cancers.

"These studies have all been in these mouse models to date," said Mana. "One idea we started with was to understand the metabolic dependencies of the tumors that can arise in a natural or pharmacological context and then target these metabolic programs to the detriment of the tumor but not the normal tissue. We are making progress with the high fat diet model. Ultimately though, the goal is to eliminate or prevent colorectal cancer in humans."

INFORMATION:

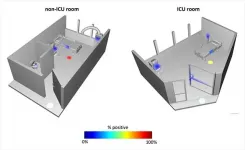

Watching what was happening around the world in early 2020, University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers knew their region would likely soon be hit with a wave of patients with COVID-19, the infection caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. They wondered how the virus persists on surfaces, particularly in hospitals, and they knew they had only a small window of time to get started if they wanted to capture a snapshot of the "before" situation -- before patients with the infection were admitted.

After a call late one Sunday night, a team assembled in the ...

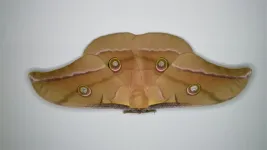

MELVILLE, N.Y., June 9, 2021 -- In the evolutionary battle between hunter and hunted, sound plays an integral part in the success or failure of the hunt. In the case of bats vs. moths, the insects are using acoustics against their winged foes.

During the 180th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, which will be held virtually June 8-10, Thomas Neil, from the University of Bristol, will discuss how moth wings have evolved in composition and structure to help them create anti-bat defenses. The session, "Moth wings are acoustic metamaterials," will take place Wednesday, June 9, at 1 p.m. Eastern U.S.

Nocturnal moths ...

MELVILLE, N.Y., June 9, 2021 -- The prolonged impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the interaction restrictions created widespread lockdown fatigue and increased social tension in multiunit housing. But small improvements in quality-of-life routines may help people cope with the health restrictions better than they previously could.

During the 180th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, which will be held virtually June 8-10, Braxton Boren, from American University, will discuss noise prevention techniques and the use of alterative acoustic stimulation to help those who find themselves in pandemic-related lockdowns. The session, "The Soundscape of Quarantine," will take place Wednesday, June 9, at 1:45 p.m. Eastern U.S.

While there have been studies about ...

The SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease (PLpro) plays an essential role in processing viral proteins needed for replication. In addition, the enzyme can cut and inactivate some human proteins important for an immune response. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Infectious Diseases have found other targets of PLpro in the human proteome, including proteins involved in cardiovascular function, blood clotting and inflammation, suggesting a link between the inactivation of these proteins and COVID-19 symptoms.

Viruses like SARS-CoV-2 make multiple proteins as one long "polyprotein." Viral enzymes called proteases recognize specific amino acid sequences in this polyprotein and cut them to release individual proteins. ...

A cell-penetrating peptide developed by researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center can prevent, in an animal model, the often-fatal septic shock that can result from bacterial and viral infections.

Their findings, published this week in Scientific Reports, could lead to a way to protect patients at highest risk for severe complications and death from out-of-control inflammatory responses to microbial infections, including COVID-19.

"Life-threatening microbial inflammation hits harder (in) patients with metabolic syndrome, a condition afflicting millions of people in the United States and worldwide," said the paper's corresponding author, Jacek Hawiger, MD, PhD, the Louise B. McGavock Chair in Medicine and Distinguished Professor of Medicine ...

BRIEFING NOTE: Researchers will announce these results at the 238th AAS meeting on Wednesday, June 9 at 12:15 p.m. E.D.T. Press registration details can be found here: https://aas.org/meetings/aas238/press. Interested journalists can also tune in to AAS briefings streamed live at: https://www.youtube.com/c/AASPressOffice. Please note that you will not be able to ask questions via YouTube; to ask questions, you'll need to register for the meeting and join the briefings via Zoom. Recordings will be archived on the AAS Press Office YouTube channel afterward.

To catch sight of a fast radio burst is to be extremely lucky in where and when you point your radio dish. Fast radio bursts, or FRBs, are oddly bright flashes of light, registering ...

OAKLAND, Calif. -- The significant declines in heart attack hospitalizations and emergency care for possible strokes seen in Northern California at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic were not seen in subsequent surges, new research from Kaiser Permanente shows.

The study, published June 2 in JAMA, suggests public health campaigns that encouraged people to seek care if they were experiencing signs or symptoms of a stroke or heart attack were effective.

"In May 2020, we reported that, in the early months of the pandemic, the weekly number of patients admitted to our hospitals for a heart attack fell to nearly half of what would be expected," said the study's lead author Matthew ...

A new study identifies a novel biomarker indicating resilience to chronic stress. This biomarker is largely absent in people suffering from major depressive disorder, and this absence is further associated with pessimism in daily life, the study finds.

Nature Communications published the research by scientists at Emory University.

The researchers used brain imaging to identify differences in the neurotransmitter glutamate within the medial prefrontal cortex before and after study participants underwent stressful tasks. They then followed the participants for four weeks, using a survey protocol to regularly assess how participants rated their expected and experienced outcomes for daily activities.

"To our knowledge, this is the first work to show ...

A new study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society suggests that survival rates after heart transplant surgery are similar in adults ages 18 to 69 and adults ages 70 and older.

Researchers examined a large U.S. database of patients who were listed as candidates for surgery to replace their failing hearts with healthier donor hearts. The researchers found that:

Only 1 in 50 people who are considered for heart transplant surgery and 1 in 50 people who receive a heart transplant are ages 70 or older.

For older adults in the study, the likelihood of surviving one or five years after a heart transplant was about the same as for younger adults.

Having a ...

Early in her career neuroscientist Allyson Mackey began thinking about molars. As a researcher who studies brain development, she wanted to know whether when these teeth arrived might indicate early maturation in children.

"I've long been concerned that if kids grow up too fast, their brains will mature too fast and will lose plasticity at an earlier age. Then they'll go into school and have trouble learning at the same rate as their peers," says Mackey, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at Penn. "Of course, not every kid who experiences stress or [is] low income will show this pattern of accelerated development."

What would help, she thought, was a scalable, objective way—a physical manifestation, ...