A national study led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital suggests that children with what is called "average risk medulloblastoma" can receive a radiation "boost" to a smaller volume of the brain at the end of a six-week course of radiation treatment and still maintain the same disease control as those receiving radiation to a larger area. But the researchers also found that the dose of the preventive radiation treatments given to the whole brain and spine over the six-week regimen cannot be reduced without reducing survival. Further, the researchers showed that patients' cancers responded differently to therapy depending on the biology of the tumors, setting the stage for future clinical trials of more targeted treatments.

Children with average risk medulloblastoma have five-year survival rates of 75% to 90%. In contrast, children with what's called "high risk medulloblastoma" have five-year survival rates of 50% to 75%. Other factors -- such as a child's age and whether the tumor has spread -- help determine the risk category. For this study, the researchers focused on patients with average risk medulloblastoma.

The findings appears online June 10 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

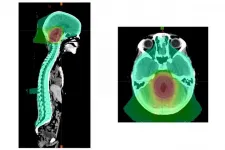

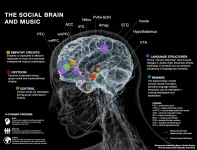

"Medulloblastoma is a devastating disease," said first and corresponding author Jeff M. Michalski, MD, the Carlos A. Perez Distinguished Professor of Radiation Oncology at Washington University. "It is a malignant brain tumor that develops in the cerebellum, the back lower part of the brain that is important for coordinating movement, speech and balance. The radiation treatment for this tumor also can be challenging, especially in younger children whose brains are actively developing in these areas. There's a balance between effectively treating the tumor without damaging children's abilities to move, think and learn."

Children with average risk medulloblastoma typically undergo surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible. They also receive chemotherapy and radiation therapy to prevent the spread of the tumor to other parts of the brain and spine through the cerebrospinal fluid.

"We wanted to investigate whether we could safely reduce the amount of radiation these patients receive -- sparing normal parts of the brain and lessening the side effects for children with this type of brain cancer -- while also maintaining effective treatment," said Michalski, also vice chair and director of clinical programs in the Department of Radiation Oncology. "We found that reducing the dose of radiation received over the six-week course of treatment had a negative impact on survival. But we also found that we could safely reduce the size of the volume of the brain that receives a radiation boost at the end of the treatment regimen. We hope such measures can help reduce the side effects of this treatment, especially in younger patients."

Collaborating with children's hospitals across the U.S. and internationally, the researchers evaluated 464 patients treated for average risk medulloblastoma that was diagnosed between ages 3 and 21. Younger patients, ages 3 to 7 -- a key time for brain development -- were randomly assigned to receive either standard dose (23.4 gray) or low dose (18 gray) radiation to the head and spine region in each of 30 treatments given over six weeks. Older patients all received the standard dose, since their brain development is less vulnerable to radiation. In addition, all patients were randomly assigned to receive two different sizes of a radiation "boost" at the end of the six weeks of therapy. For the boost, all patients received a cumulative radiation dose of 54 gray to either the entire region of the brain called the posterior fossa, which includes the cerebellum, or to a smaller region of the brain that includes the original outline of the tumor plus an additional margin of up to about two centimeters beyond the original tumor boundary.

"The patients who received the smaller boost did just as well as those who received the whole posterior fossa boost," said Michalski, who treats patients at Siteman Kids at Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis Children's Hospital. "Many doctors have already adopted this smaller boost volume, but now we have high-quality evidence that this is indeed safe and effective."

For patients receiving the smaller boost volume, 82.5% survived five years with no worsening of the cancer. And for those receiving the larger boost volume to the entire posterior fossa, 80.5% survived five years with no worsening of the disease. These numbers were not statistically different. In a subset of tumors with mutations in a gene called SHH, patients actually showed improved survival with the smaller boost volume.

But for the younger children, the lower dose of radiation over six weeks did not result in similar survival numbers. Of those receiving the standard dose of craniospinal radiation, about 83% survived five years with no worsening of the cancer. Of those receiving the lower dose, about 71% survived five years with no worsening of the cancer. That difference in survival was statistically significant.

"We saw higher rates of recurrence and tumor spreading in the younger patients receiving the lower dose of craniospinal radiation," Michalski said. "In general, it's not safe to lower the dose of radiation in children with medulloblastoma even if we know the lower dose might spare their cognitive function. However, a specific subgroup of patients -- those with mutations in a gene called WNT -- did well on the lower dose, so we're now doing studies just with these specific patients to see if we can safely lower the radiation dose for them."

The tumors were categorized into four molecular subgroups based on their gene expression and predicted biology. The first group's tumors have mutations in WNT signaling pathways; the second have mutations in the SHH gene; and the third and fourth groups' tumors each have different and more complex patterns of gene mutations. The researchers found differences in tumors' responses to treatment based on tumor biology that can guide the design of future clinical trials.

"We've made great strides over the last 15 years in appreciating the molecular diversity of medulloblastoma," said senior author Paul Northcott, PhD, of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. "We performed whole-exome sequencing and DNA methylation profiling to assign patients to molecular subgroups. This was a critical step in contextualizing this trial based on the latest biology and showed us some important differences in how children respond to therapy that would otherwise not have been clear. Results from this study will play a vital role in designing the next generation of clinical trials for children with medulloblastoma."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including a National Clinical Trials Network Operations Center Grant, number U10CA180886; a Children's Oncology Group (COG) Chairs Grant, number U10CA098543; a National Clinical Trials Network Statistics & Data Center Grant, number U10CA098413; and other NCI grants, including U10CA180899, QARC U10CA29511, IROC U24CA180803 and COG Biospecimen Bank Grant U24CA196173. Funding was also provided by St. Baldrick's Foundation, The Brain Tumor Charity, American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

Michalski JM et al. A children's oncology group phase III trial of reduced dose and volume radiotherapy with chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. June 10, 2021.

Washington University School of Medicine's 1,500 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, consistently ranking among the top medical schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.