(Press-News.org) Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine used an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm to sift through terabytes of gene expression data -- which genes are "on" or "off" during infection -- to look for shared patterns in patients with past pandemic viral infections, including SARS, MERS and swine flu.

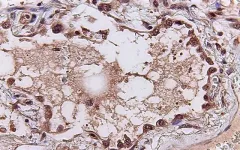

Two telltale signatures emerged from the study, published June 11, 2021 in eBiomedicine. One, a set of 166 genes, reveals how the human immune system responds to viral infections. A second set of 20 signature genes predicts the severity of a patient's disease. For example, the need to hospitalize or use a mechanical ventilator. The algorithm's utility was validated using lung tissues collected at autopsies from deceased patients with COVID-19 and animal models of the infection.

"These viral pandemic-associated signatures tell us how a person's immune system responds to a viral infection and how severe it might get, and that gives us a map for this and future pandemics," said Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor of cellular and molecular medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center.

Ghosh co-led the study with Debashis Sahoo, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics at UC San Diego School of Medicine and of computer science and engineering at Jacobs School of Engineering, and Soumita Das, PhD, associate professor of pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

During a viral infection, the immune system releases small proteins called cytokines into the blood. These proteins guide immune cells to the site of infection to help get rid of the infection. Sometimes, though, the body releases too many cytokines, creating a runaway immune system that attacks its own healthy tissue. This mishap, known as a cytokine storm, is believed to be one of the reasons some virally infected patients, including some with the common flu, succumb to the infection while others do not.

But the nature, extent and source of fatal cytokine storms, who is at greatest risk and how it might best be treated have long been unclear.

"When the COVID-19 pandemic began, I wanted to use my computer science background to find something that all viral pandemics have in common -- some universal truth we could use as a guide as we try to make sense of a novel virus," Sahoo said. "This coronavirus may be new to us, but there are only so many ways our bodies can respond to an infection."

The data used to test and train the algorithm came from publicly available sources of patient gene expression data -- all the RNA transcribed from patients' genes and detected in tissue or blood samples. Each time a new set of data from patients with COVID-19 became available, the team tested it in their model. They saw the same signature gene expression patterns every time.

"In other words, this was what we call a prospective study, in which participants were enrolled into the study as they developed the disease and we used the gene signatures we found to navigate the uncharted territory of a completely new disease," Sahoo said.

By examining the source and function of those genes in the first signature gene set, the study also revealed the source of cytokine storms: the cells lining lung airways and white blood cells known as macrophages and T cells. In addition, the results illuminated the consequences of the storm: damage to those same lung airway cells and natural killer cells, a specialized immune cell that kills virus-infected cells.

"We could see and show the world that the alveolar cells in our lungs that are normally designed to allow gas exchange and oxygenation of our blood, are one of the major sources of the cytokine storm, and hence, serve as the eye of the cytokine storm," Das said. "Next, our HUMANOID Center team is modeling human lungs in the context of COVID-19 infection in order to examine both acute and post-COVID-19 effects."

The researchers think the information might also help guide treatment approaches for patients experiencing a cytokine storm by providing cellular targets and benchmarks to measure improvement.

To test their theory, the team pre-treated rodents with either a precursor version of Molnupiravir, a drug currently being tested in clinical trials for the treatment of COVID-19 patients, or SARS-CoV-2-neutralizing antibodies. After exposure to SARS-CoV-2, the lung cells of control-treated rodents showed the pandemic-associated 166- and 20-gene expression signatures. The treated rodents did not, suggesting that the treatments were effective in blunting cytokine storm.

"It is not a matter of if, but when the next pandemic will emerge," said Ghosh, who is also director of the Institute for Network Medicine and executive director of the HUMANOID Center of Research Excellence at UC San Diego School of Medicine. "We are building tools that are relevant not just for today's pandemic, but for the next one around the corner."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the study include: Gajanan D. Katkar, Soni Khandelwal, Mahdi Behroozikhah, Amanraj Claire, Vanessa Castillo, Courtney Tindle, MacKenzie Fuller, Sahar Taheri, Stephen A. Rawlings, Victor Pretorius, David M. Smith, Jason Duran, UC San Diego; Thomas F. Rogers, Scripps Research and UC San Diego; Nathan Beutler, Dennis R. Burton, Scripps Research; Sydney I. Ramirez, La Jolla Institute for Immunology; Laura E. Crotty Alexander, VA San Diego Healthcare System and UC San Diego; Shane Crotty, Jennifer M. Dan, La Jolla Institute for Immunology and UC San Diego.

Astronomers from University of Warwick and University of Exeter modelling the future of unusual planetary system found a solar system of planets that will 'pinball' off one another

Today, the system consists of four massive planets locked in a perfect rhythm

Study shows that this perfect rhythm is likely to hold for 3 billion years - but the death of its sun will cause a chain reaction and set the interplanetary pinball game in motion

Four planets locked in a perfect rhythm around a nearby star are destined to be pinballed around their solar system when their sun eventually dies, according to a study led by the University of Warwick that peers into its future.

Astronomers have modelled how the change in gravitational forces in the system as a result ...

When is a weed not a weed?

Can native plants be weeds?

Sweet pittosporum (Pittosporum undulatum) was once a well-behaved tree growing in gullies from Gippsland in Victoria up to Brisbane in Queensland.

But it is now a major problem, leading to an almost complete suppression of native vegetation where it has invaded. Programs to clear it have successfully allowed indigenous plants to return, and within 15 years, with moderate follow up, treated sites are well on the way to successful restoration.

However, there has been some debate on whether this is good or bad for birds such as the threatened Powerful Owl.

New research by Monash University scientists from the School of Biological Sciences published today in Ecological Solutions and ...

Astronomers have spotted a giant 'blinking' star towards the centre of the Milky Way, more than 25,000 light years away.

An international team of astronomers observed the star, VVV-WIT-08, decreasing in brightness by a factor of 30, so that it nearly disappeared from the sky. While many stars change in brightness because they pulsate or are eclipsed by another star in a binary system, it's exceptionally rare for a star to become fainter over a period of several months and then brighten again.

The researchers believe that VVV-WIT-08 may belong to a new class of 'blinking giant' binary star system, where a giant star ? 100 times larger ...

Oncotarget published "The presence of polymorphisms in genes controlling neurotransmitter metabolism and disease prognosis in patients with prostate cancer: a possible link with schizophrenia" reported that polymorphisms of neurotransmitter metabolism genes were studied in patients with prostate cancer (PC) characterized by either reduced or extended serum prostate-specific antigen doubling time corresponding to unfavorable and favorable disease prognosis respectively.

The following gene polymorphisms known to be associated with neuropsychiatric disorders were investigated:

A. The STin2 VNTR in the serotonin transporter SLC6A4 gene;

B. The 30-bp VNTR in the monoamine oxidase A MAOA gene;

C. The Val158Met polymorphism in the catechol-ortho-methyltransferase ...

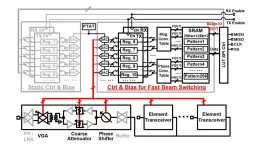

Scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) and NEC Corporation jointly develop a 28-GHz phased-array transceiver that supports efficient and reliable 5G communications. The proposed transceiver outperforms previous designs in various regards by adapting fast beam switching and leakage cancellation mechanism.

With the recent emergence of innovative technologies, such as the Internet of Things, smart cities, autonomous vehicles, and smart mobility, our world is on the brink of a new age. This stimulates the use of millimeter-wave bands, which have far more signal bandwidth, to accommodate these new ideas. 5G can offer data ...

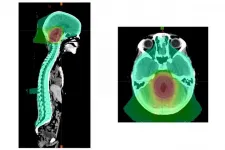

Medulloblastoma is a rare but devastating childhood brain cancer. This cancer can spread through the spinal fluid and be deposited elsewhere in the brain or spine. Radiation therapy to the whole brain and spine followed by an extra radiation dose to the back of the brain prevents this spread and has been the standard of care. However, the radiation used to treat such tumors takes a toll on the brain, damaging cognitive function, especially in younger patients whose brains are just beginning to develop.

A national study led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital suggests that children with what is called "average risk medulloblastoma" can receive a radiation "boost" to a smaller ...

Metformin is a widely prescribed blood sugar-lowering drug. It is often used as an early therapy (in combination with diet and lifestyle changes) for type 2 diabetes, which afflicts more than 34 million Americans.

Metformin works by lowering glucose production in the liver, reducing blood sugar levels that, in turn, improve the body's response to insulin. But scientists have also noted that metformin possesses anti-inflammatory properties, though the basis for this activity was not known.

In a study published online June 8, 2021 in the journal END ...

Married men who don't help out around the house tend to bring home bigger paychecks than husbands who play a bigger role on the domestic chores front.

New research from the University of Notre Dame shows that "disagreeable" men in opposite-sex marriages are less helpful with domestic work, allowing them to devote greater resources to their jobs, which results in higher pay.

In contemporary psychology, "agreeableness" is one of the "Big Five" dimensions used to describe human personality. It generally refers to someone who is warm, sympathetic, kind and cooperative. Disagreeable people do not tend to exhibit these characteristics, and they tend to ...

An estimated 8 million tons of plastic trash enters the ocean each year, and most of it is battered by sun and waves into microplastics--tiny flecks that can ride currents hundreds or thousands of miles from their point of entry.

The debris can harm sea life and marine ecosystems, and it's extremely difficult to track and clean up.

Now, University of Michigan researchers have developed a new way to spot ocean microplastics across the globe and track them over time, providing a day-by-day timeline of where they enter the water, how they move and where they tend to collect.

The approach relies on ...

Have you ever been cut off in traffic by another driver, leaving you still seething miles later? Or been interrupted by a colleague in a meeting, and found yourself replaying the event in your head even after you've left work for the day? Minor rude events like this happen frequently, and you may be surprised by the magnitude of the effects they have on our decision-making and functioning. In fact, recent research co-authored by management professor Trevor Foulk at the University of Maryland's Robert H. Smith School of Business suggests that in certain situations, incidental rudeness like this can be deadly.

In "Trapped ...