(Press-News.org) Our ability to confront global crises, from pandemics to climate change, depends on how we interact and share information.

Social media and other forms of communication technology restructure these interactions in ways that have consequences. Unfortunately, we have little insight into whether these changes will bring about a healthy, sustainable and equitable world. As a result, researchers now say that the study of collective behavior must rise to a "crisis discipline," just like medicine, conservation and climate science have done, according to a new paper published June 14 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"We have built and adopted technology that alters behavior at global scales without a theory of what will happen or a coherent strategy for reducing harm," said Joseph B. Bak-Coleman, the lead author and a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Washington's Center for an Informed Public.

Social media and other technological developments have radically reshaped the way that information flows on a global scale. These platforms are driven to maximize engagement and profitability, not to ensure sustainability or accurate information -- and the vulnerability of these systems to misinformation and disinformation poses a dire threat to health, peace, global climate and more.

No one, not even the platform creators themselves, have much understanding of how their design decisions impact human collective behavior, the authors argue.

"We urgently need to understand this and move forward with focus on developing social systems that promote well-being instead of creating shareholder value by commandeering our collective attention," said co-author Carl T. Bergstrom, a UW professor of biology and faculty at the Center for an Informed Public.

Collective behavior and other complex systems are fragile. "When perturbed, complex systems tend to exhibit finite resilience followed by catastrophic, sudden, and often irreversible changes," the authors write.

While there are studies and disciplines that focus on complex systems in the natural world, "we have a far poorer understanding of the functional consequences of recent large-scale changes to human collective behavior and decision making," the authors write.

Averting catastrophe in the medium term (e.g., coronavirus) and long term (e.g., climate change, food security) will require rapid and effective collective behavioral responses -- yet it remains unknown whether human social dynamics will yield such responses.

"We have seen individual studies about how climate-change disinformation gets over-represented even in the mainstream media, and studies that show that in digital media that problem only gets worse," said co-author Jennifer Jacquet, an associate professor of environmental studies at New York University.

Lacking a developed framework, tech companies have also fumbled their way through the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, unable to stem the "infodemic" of misinformation that impedes public acceptance of pandemic control measures such as wearing masks and widespread testing for the virus.

The situation parallels challenges faced in conservation biology and climate science, where insufficiently regulated industries optimize profits while undermining the stability of ecological and Earth systems.

"If we have a decade or so to act on climate change, we have far less time to sort out our social systems," Bak-Coleman said.

Historically collective behavior has best been understood as when animals or people exhibit coordinated action without an obvious leader. This includes how fish school to evade predators or when a crowd spontaneously breaks into applause or becomes silent.

That thinking has evolved over the past decade, the authors write, from a phenomena to a contemporary view of collective action as framework that reveals how interaction between individuals gives rise to collective action.

INFORMATION:

Additional co-authors on the paper include Rachel Moran at the UW; Mark Alfano at Delft University of Technology and Australian Catholic University; Wolfram Barfuss at University of Tübingen; Miguel A. Centeno, Andrew S. Gersick, Daniel I. Rubenstein and Elke U. Weber at Princeton University; Iain D. Cousin at University of Konstanz; Jonathan F. Donges at Stockholm University; Mirta Galesic and Albert B. Kao at Santa Fe Institute; Pawel Romanczuk at Humboldt Universität zu Berlin; Kaia J. Tombak at Hunter College of the City University of New York; and Jay J. Van Bavel at New York University.

Funding came from the UW eScience Institute, the Knight Foundation, the UW for an Informed Public, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the National Science Foundation, The Max Planck Society, The Baird Society, The Emmy Noether Program, The Santa Fe Institute and the U.S. Navy's Office of Naval Research.

For more information, contact Bak-Coleman at joebak@uw.edu.

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) -- Scientists at UC Santa Barbara, University of Southern California (USC), and the biotechnology company Regenerative Patch Technologies LLC (RPT) have reported new methodology for preservation of RPT's stem cell-based therapy for age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The new research, recently published in Scientific Reports, optimizes the conditions to cryopreserve, or freeze, an implant consisting of a single layer of ocular cells generated from human embryonic stem cells supported by a flexible scaffold about 3x6 mm in size. ...

When lithium ions flow in and out of a battery electrode during charging and discharging, a tiny bit of oxygen seeps out and the battery's voltage - a measure of how much energy it delivers - fades an equally tiny bit. The losses mount over time, and can eventually sap the battery's energy storage capacity by 10-15%.

Now researchers have measured this super-slow process with unprecedented detail, showing how the holes, or vacancies, left by escaping oxygen atoms change the electrode's structure and chemistry and gradually reduce how much energy it can store.

The results contradict some of the assumptions scientists had made about this process and could suggest new ways of engineering electrodes to prevent it.

The research team from the Department of Energy's ...

MISSOULA - Those in love with the outdoors can spend their entire lives chasing that perfect campsite. New University of Montana research suggests what they are trying to find.

Will Rice, a UM assistant professor of outdoor recreation and wildland management, used big data to study the 179 extremely popular campsites of Watchman Campground in Utah's Zion National Park. Campers use an online system to reserve a wide variety of sites with different amenities, and people book the sites an average of 51 to 142 days in advance, providing hard data about demand.

Along with colleague Soyoung Park of Florida Atlantic University, Rice sifted through nearly 23,000 reservations. The researchers found that price and availability of electricity were the largest drivers of demand. Proximity ...

Albeit very small, with a carapace width of only 3 cm, the Atlantic mangrove fiddler crab Leptuca thayeri can be a great help to scientists seeking to understand more about the effects of global climate change. In a study published in the journal Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, Brazilian researchers supported by São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP show how the ocean warming and acidification forecast by the end of the century could affect the lifecycle of these crustaceans.

Embryos of L. thayeri were exposed to a temperature rise of 4 °C and a pH reduction of 0.7 against the average for their habitat, growing faster as a result. However, a larger number of ...

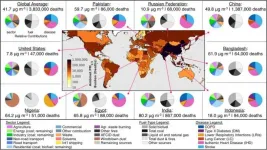

An interdisciplinary group of researchers from across the globe has comprehensively examined the sources and health effects of air pollution -- not just on a global scale, but also individually for more than 200 countries.

They found that worldwide, more than one million deaths were attributable to the burning of fossil fuels in 2017. More than half of those deaths were attributable to coal.

Findings and access to their data, which have been made public, were published today in the journal Nature Communications.

Pollution is at once a global crisis and a devastatingly personal problem. It is analyzed by satellites, but PM2.5 -- tiny particles that can infiltrate a person's lungs -- can also sicken a person who cooks dinner nightly on a cookstove.

"PM2.5 ...

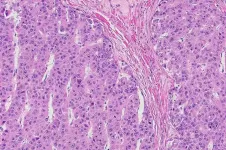

Treatment options for a deadly liver cancer, fibrolamellar carcinoma, are severely lacking. Drugs that work on other liver cancers are not effective, and although progress has been made in identifying the specific genes involved in driving the growth of fibrolamellar tumors, these findings have yet to translate into any treatment. For now, surgery is the only option for those affected--mostly children and young adults with no prior liver conditions.

Sanford M. Simon and his group understood that patients dying of fibrolamellar could not afford to wait. "There are people who need therapy now," he says. So his group threw the kitchen sink at the problem and tested over 5,000 compounds, either already approved for other clinical uses or in clinical ...

DALLAS - June 14, 2021 - Overweight cancer patients receiving immunotherapy treatments live more than twice as long as lighter patients, but only when dosing is weight-based, according to a study by cancer researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

The findings, published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, run counter to current practice trends, which favor fixed dosing, in which patients are given the same dose regardless of weight. The study included data on nearly 300 patients with melanoma, lung, kidney, and head and neck cancers ...

Leesburg, VA, June 14, 2021--According to ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), high-dose intranodal lymphangiography (INL) with ethiodized oil is a safe and effective procedure for treating high-output postsurgical chylothorax with chest tube removal in 83% of patients.

"To our knowledge," wrote corresponding author Geert Maleux of University Hospitals in Leuven, Belgium, "no data are available on the safety or potential beneficial effect of injecting higher doses of ethiodized oil to treat patients with refractory postoperative chylothorax."

All 18 patients (mean, 67 years; range, ...

A team of scientists from Kaunas University of Technology and Lithuanian Energy Institute proposed a method to convert lint-microfibers found in clothes dryers into energy. They not only constructed a pilot pyrolysis plant but also developed a mathematical model to calculate possible economic and environmental outcomes of the technology. Researchers estimate that by converting lint microfibers produced by 1 million people, almost 14 tons of oil, 21.5 tons of gas and nearly 10 tons of char could be produced.

Each year, the global population consumes approximately 80 billion pieces of clothing and approximately €140 million worth of it goes into landfill. This is accompanied by large amounts of emissions, causing serious environmental and health problems. One of the ways to lessen ...

A new study found higher education students are more engaged and motivated when they are taught using playful pedagogy rather than the traditional lecture-based method. The study was conducted by University of Colorado Denver counseling researcher Lisa Forbes and was published in the Journal of Teaching and Learning.

While many educators in higher education believe play is a method that is solely used for elementary education, Forbes argues that play is important in post-secondary education to enhance student learning outcomes.

Throughout the spring 2020 semester, Forbes observed students who were enrolled in three of her courses between the ages of 23-43. To introduce playful pedagogy, Forbes included games and play, not always tied to the ...