Through surveys and GPS monitoring, Stears and his colleagues, Wendy Turner, Doug McCauley and Melissa Schmitt, revealed that reduced dry-season flows in the Great Ruaha River indirectly spread the disease by affecting hippo movement. The results, which appear in the journal Ecosphere(link is external), present a unique perspective on disease ecology and illustrate how anthropogenic changes can impact wildlife and human health.

The ecology of wildlife disease was far out of mind during the dry season in 2016, when Stears and his team outfitted 10 male hippos with GPS collars. The researchers sought to track the animals' movements to better understand their behavior and ecology, especially in light of reduced flows along many of Africa's major rivers. The resulting study was the first to track hippo movement and land use, and finally uncovered some of the basic facts about hippos' spatial ecology.

Then the anthrax came.

"This wasn't something I actually set out to study," said Stears, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology. "You can't plan for an outbreak to occur; it just happens."

Stears was in the field from 2016 to 2017 conducting hippo counts and maintaining equipment. The GPS tracking collars had been on the animals for about a year, roughly as long as they're supposed to last before dropping off. Noticing one of the collars hadn't moved for a couple of days, he figured it had fallen off. It appeared to be in a nearby pool, so Stears hiked out to retrieve it. "I turned around a bend in the river, and there was a hippo pool with about six or so hippo carcasses," he recalled. Stears had stumbled upon an anthrax outbreak.

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis, which can manifest in a variety of ways depending on how it's contracted. The bacterium is notable for its ability to produce spores that can lie dormant in the soil for years. Notably, in outbreaks like the one in this study, animals can only spread the disease once they die.

Although he isn't a disease ecologist, Stears quickly realized his GPS data could illuminate aspects of the outbreak. There didn't seem to be any existing studies that combined a spatio-temporal account of an active anthrax outbreak with wildlife movement, he explained. "So this was really a unique opportunity to answer some questions that hadn't really been answered before."

"We can't predict when an anthrax outbreak will occur, so it's impossible to plan such a study," added co-author Wendy Turner of the U.S. Geological Survey and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "This project is in part a fantastic bit of luck (for understanding disease transmission, not for the hippos), and in part very clever and quick thinking by Keenan and Melissa at UCSB, to capitalize on such a unique opportunity.

"I have been studying anthrax for years in Namibia, with many more GPS-collared hosts monitored than the 10 in this study," she continued, "and I still haven't had any of our individuals succumb to the disease."

The team first had to determine how many hippos in this population had interacted with potentially infected pools. That meant identifying which of the many disconnected pools along this stretch of the Great Ruaha River were infected. Stears' colleagues at Ruaha National Park conducted sampling for the pathology to confirm the anthrax outbreak.

Stears and his team conducted daily counts of both live and dead hippos in these pools. The surveys enabled them to track the disease's spread, its rate and direction. The scientists were also curious where the hippos were coming from, where they were going and whether the outbreak was influencing their behavior.

The researchers linked this information with the hippo movement data they had from the GPS collars. Four of the 10 hippos they had tracked could have caught the disease, Stears said, and of those, three died.

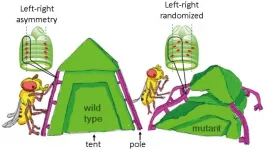

The team found that infection had no noticeable effect on a hippo's movement. Infected individuals roamed just as much as healthy hippos. "This has important implications for how far a single individual could potentially vector the disease before its death and create new infectious reservoirs," Stears said. Under certain conditions, wildlife can succumb to infection within a few days. Even if this is the case, a hippo can walk about seven kilometers over the course of a night in search of water. Thus, hippos can quickly move the disease over large distances.

What's more, the animals didn't appear to actively avoid carcasses. Why? Well, dry times are not good times to be a hippo. Normally, species avoid the bodies of their own kind. But with suitable ponds so scarce, the amphibious animals were forced to remain in pools alongside the dead.

"The drying of rivers is one of the major reasons why these outbreaks have gotten so bad over the years," Stears explained. "As the river dries, hippos are forced to congregate in the remaining river pools. Now this paper's showing that their movements spread the disease as well."

Anthrax outbreaks are a natural occurrence, but drying rivers are making them worse. As pools dry up, hippos either pack into those that remain or move to find new ones. Increased crowding and social interactions can drive up physiological stress, which scientists have linked to a greater susceptibility to infection.

Additionally, altered hippo movements as they search for new pools raise the risk of exposure to anthrax reservoirs as well as the duration that they interact with these reservoirs. Aggressive interactions around the remaining pools mean that hippos frequently visit several in a given night. All these factors have exacerbated anthrax outbreaks in hippo populations.

Stears noted that hippos also appear particularly susceptible to these outbreaks, aggregating as they do in small, dirty pools during the dry season. Other animals avoid drinking from hippo pools during these times because of all the dung that has accumulated due to the lack of river flow. Instead, they seek out shallower puddles that are cleaner, which potentially protects them from contracting lethal doses of the disease.

"Understanding disease outbreaks in hippos is especially important," said co-author Doug McCauley(link is external), an associate professor of ecology, evolution, and marine biology (EEMB) at UC Santa Barbara. "People don't often realize that hippos are a vulnerable species that has declined in many areas. There are far less hippos, for example, than African elephants. Their outlook is further complicated by potential impacts that climate change may have on rivers and how this change might amplify disease outbreak risk."

Stears plans to start looking at historical records of river flow across Africa and linking changes in hydrology to past anthrax outbreak timing and severity. There hasn't been much research on anthrax and river flow, he said; most of the work has been terrestrial. The historical records could be a treasure chest of information.

Shedding light on the factors that influence disease dynamics helps scientists predict how disturbances might affect future outbreaks. With this information, they can begin to assess how future circumstances could affect the extent and severity of an anthrax outbreak, as well as the probability that it jumps to other species of wildlife, livestock and even humans.

"Hippos can be considered the canary in the coal mine," added co-author Melissa Schmitt(link is external), an EEMB postdoctoral researcher. "Their sensitivity to adverse conditions makes them a good indicator of how global change may influence disease dynamics and overall wildlife health.

In all, the paper represents a confluence of events that offered an unparalleled opportunity to explore novel disease dynamics. "You can only get this kind of information from having an animal that is collared and actually infected," Stears said. "So this unique situation allowed us to answer questions that you just can't normally answer without having everything lined up."

INFORMATION: