(Press-News.org) June 15, 2021 - Canadian researchers have discovered that a bee thought to be one of the rarest in the world, as the only representative of its genus, is no more than an unusual specimen of a widespread species.

Scientists with the Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN) and York University have reclassified the mystery bee, collected somewhere in Nevada in the 1870s, as Brachymelecta californica. They note that it's an aberrant individual of a species, the California digger-cuckoo bee, that is part of a group that includes five other species. All are cleptoparasitic bees, with females that lay eggs in the nests of digger bees. Brachymelecta californica itself is known to be widespread from western Canada to southern Mexico.

The paper setting the record straight is published today in the European Journal of Taxonomy. "The unusual specimen has puzzled bee researchers for decades, and deceived some of the world's great experts on bee taxonomy" says Dr. Thomas Onuferko, research associate with the CMN and the study's lead author. "They can now stop searching for more examples of this 'rare' bee."

The bee was first described in 1879 by American entomologist Ezra Townsend Cresson from the Nevada specimen. It was later placed in its own genus, and renamed Brachymelecta mucida in 1939, a name that has only ever been associated with this lone specimen.

It stood apart from other related bees because its abdomen's dorsal surface is unusually covered in pale hairs, these being partly dark in other specimens of what are now understood to be the same species. Another unusual feature is that the fore wings of the specimen each have two submarginal cells (the normal number for the bees in this group is three). These two features had confused everyone, until now.

In 2019, Onuferko was able to examine the rare specimen during a visit to the collections at Philadelphia's Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. There, he discovered a series of other specimens with the same vague locality labels, but these bees were identified as Xeromelecta californica, a species that was also described by Cresson in the year before the description of the mystery species.

In some of the specimens, the pattern of veins in the wings is the same as in the mystery specimen. "At that point, I made the connection that these specimens might all be the same species," says Onuferko.

This connection was further boosted by the discovery in Dr. Laurence Packer's collection at York University of a bee that also had conspicuously pale hairs on its entire abdomen. DNA barcoding confirmed the specimen to be Xeromelecta californica. Hairs that are normally dark in this species were completely light. Onuferko and Packer, who also collaborated on the study, concluded that the hairs likely lacked pigmentation due to a form of partial albinism.

The finding surprised Packer because some of the best bee biologists had studied the specimen, but he adds, "Rummaging around in old collections is actually an important thing to do. There is a lot to discover within museum collections, and in this case the rummaging revealed that a rare bee is not so rare after all."

The discovery has prompted an unusual name change, which is based on rules of the organization that governs the naming of animal species--the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature. Due to the chronology of dates in which the bees' various genus and species names were published, Brachymelecta californica takes precedence as the accepted name, and the five related species classified as Xeromelecta are now also part of the genus Brachymelecta. This genus, previously known from a single specimen, is now known from most of the bee collections in North America.

"The reclassification of this bee shows why it's important to describe new taxa from multiple examples and why entomologists collect specimens in series," explains Onuferko. It is impossible to know the range of variation within a species with a single specimen, and describing new species from a lone sample risks mistaking an aberrant specimen for a new species.

New species still occasionally get described from single specimens; however, in such cases the new species should be thoroughly justified (using both molecular and morphological evidence, if possible), to avoid taxonomic problems down the line.

The study's authors explain that many researchers have written about the mystery bee under its earlier classification as Brachymelecta mucida, meaning that intellectual resources were dedicated to a specimen that did not merit them. "Bee collectors were effectively in search of an elusive 'white whale; or more appropriately, a 'whitish bee', a species that evidently only existed in the minds of taxonomists," says Onuferko.

INFORMATION:

About the Canadian Museum of Nature

Saving the world through evidence, knowledge and inspiration! The Canadian Museum of Nature is Canada's national museum of natural history and natural sciences. The museum provides evidence-based insights, inspiring experiences and meaningful engagement with nature's past, present and future. It achieves this through scientific research, a 14.6-million specimen collection, education programs, signature and travelling exhibitions, and a dynamic web site, nature.ca.

About York University

York University is a modern, multi-campus, urban university located in Toronto, Ontario. Backed by a diverse group of students, faculty, staff, alumni and partners, we bring a uniquely global perspective to help solve societal challenges, drive positive change and prepare our students for success. York's fully bilingual Glendon Campus is home to Southern Ontario's Centre of Excellence for French Language and Bilingual Postsecondary Education. York's campuses in Costa Rica and India offer students exceptional transnational learning opportunities and innovative programs.

Information for media:

Dan Smythe

Head, Media Relations

Canadian Museum of Nature

613-698-9253; dsmythe@nature.ca

Sandra McLean

Senior Media Relations Officer

York University

416-272-6317; sandramc@yorku.ca

A recent UCLA clinical trial has shown encouraging results in helping daily smokers who are also heavy drinkers quit smoking and cut down their alcohol intake.

The study of 165 people tested two prescription drugs -- varenicline, for smoking addiction, and naltrexone, which is used to treat alcoholism. Studies have shown that varenicline, marketed under the brand name Chantix, may also be effective in reducing alcohol consumption.

Participants, who ranged in age from 21 to 65, smoked at least five cigarettes a day, with male participants generally consuming more than 14 drinks a week and women more than seven per week.

Over the 12-week study period, each participant received 2 milligrams of varenicline twice a day. Roughly half the group -- 83 participants -- also received a 50-milligram ...

Hippopotamus aren't the first thing that come to mind when considering epidemiology and disease ecology. And yet these amphibious megafauna offered UC Santa Barbara ecologist Keenan Stears(link is external) a window into the progression of an anthrax outbreak that struck Ruaha National Park, Tanzania, in the dry season of 2017.

Through surveys and GPS monitoring, Stears and his colleagues, Wendy Turner, Doug McCauley and Melissa Schmitt, revealed that reduced dry-season flows in the Great Ruaha River indirectly spread the disease by affecting hippo movement. The results, which appear in the journal Ecosphere(link is external), present a unique perspective on disease ecology and illustrate how anthropogenic changes can impact wildlife and human health.

The ...

A team of scientists at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) has developed millimetre-sized robots that can be controlled using magnetic fields to perform highly manoeuvrable and dexterous manipulations. This could pave the way to possible future applications in biomedicine and manufacturing.

The research team created the miniature robots by embedding magnetic microparticles into biocompatible polymers -- non-toxic materials that are harmless to humans. The robots are 'programmed' to execute their desired functionalities when magnetic fields are applied.

The made-in-NTU robots improve on many existing small-scale robots by optimizing their ability to move ...

Is artificial intelligence the key to preventing relapse of severe mental illness?

New AI software developed by researchers at Flinders University shows promise for enabling timely support ahead of relapse in patients with severe mental illness.

The AI2 (Actionable Intime Insights) software, developed by a team of digital health researchers at Flinders University, has undergone an eight-month trial with psychiatric patients from the Inner North Community Health Service, located in Gawler, South Australia.

The digital tool is tipped to revolutionise consumer-centric timely mental health treatment provision outside hospital, with researchers labelling it as readily available and scalable.

In the trial of 304 ...

Exposure to the rhinovirus, the most frequent cause of the common cold, can protect against infection by the virus which causes COVID-19, Yale researchers have found.

In a new study, the researchers found that the common respiratory virus jump-starts the activity of interferon-stimulated genes, early-response molecules in the immune system which can halt replication of the SARS-CoV-2 virus within airway tissues infected with the cold.

Triggering these defenses early in the course of COVID-19 infection holds promise to prevent or treat the infection, ...

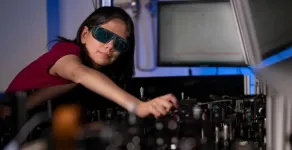

Researchers from The Australian National University (ANU) have developed new technology that allows people to see clearly in the dark, revolutionising night-vision.

The first-of-its-kind thin film, described in a new article published in Advanced Photonics, is ultra-compact and one day could work on standard glasses.

The researchers say the new prototype tech, based on nanoscale crystals, could be used for defence, as well as making it safer to drive at night and walking home after dark.

The team also say the work of police and security guards - who regularly employ night vision - will be easier and safer, reducing chronic neck injuries from currently bulk night-vision devices.

"We have made the invisible visible," lead researcher Dr Rocio Camacho Morales said. ...

Data collected for over two decades shows that rising Baltic Sea water temperature is one of the main factors in the increasingly earlier appearance and faster growth of Baltic herring larvae.

Baltic herring (Clupea harengus membras) is commercially the most important fish species in Finland, and an important part of the Baltic marine ecosystem. Conditions during herring spawning may have cascading effects on the whole Baltic ecosystem.

According to a recent research, both developmental stages in Baltic herring larvae, small and large, have shifted their timing to earlier dates.

"This suggests that herring spawn earlier and larvae grow faster, by about 7.7 days per decade. Water ...

Rising numbers of liver cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities has led experts at Flinders University to call for more programs, including mobile liver clinics and ultrasound in rural and remote Australia.

The Australian study just published in international Lancet journal EClinicalMedicine reveals the survival difference was largely accounted for by factors other than Indigenous status - including rurality, comorbidity burden and lack of curative therapy.

The study of liver cancer, or Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), included 229 Indigenous and 3587 non-Indigenous HCC cases in South Australia, Queensland and the ...

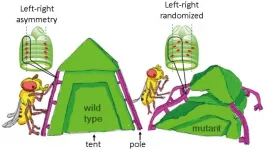

Osaka, Japan - On the outside, animals often appear bilaterally symmetrical with mirror-image left and right features. However, this balance is not always reflected internally, as several organs such as the lungs and intestines are left-right (LR) asymmetrical. Researchers at Osaka University, using an innovative technique for imaging movement of cell nuclei in living tissue, have determined the patterns of nuclear alignment responsible for LR-asymmetrical shaping of internal organs in the developing embryo.

Embryogenesis involves complex genetic and molecular processes that transform a single-celled zygote into a complete, living individual with multiple functional axes, including the LR axis. A long-standing conundrum of Developmental ...

Researchers at the University of Helsinki and the Beatson Institute for Cancer Research in Glasgow have discovered how mutated cells promote their chances to form cancer. Typically, the accumulation of harmful cells is prevented by active competition between multiple stem cells in intestinal glands, called crypts.

"The functioning of intestinal stem cells relies on growth factors, named Wnts, produced by the surrounding environment. Intestinal cancers typically originate from stem cells where mutations allow growth independent of these factors. When we removed a gene called Notum, which renders Wnts inactive, from mutated stem cells, the number of precancerous adenomas in the intestine was greatly reduced. We found that ...