(Press-News.org) Antidepressants can help humans emerge from the darkness of depression. Expose crayfish to antidepressants, and they too become more outgoing -- but that might not be such a positive thing for these freshwater crustaceans, according to a new study led by scientists with the University of Florida.

"Low levels of antidepressants are found in many water bodies," said A.J. Reisinger, lead author of the study and an assistant professor in the UF/IFAS soil and water sciences department. "Because they live in the water, animals like crayfish are regularly exposed to trace amounts of these drugs. We wanted to know how that might be affecting them," he said.

Antidepressants can get into the environment through improper disposal of medications, Reisinger said. In addition, people taking antidepressants excrete trace amounts when they use the bathroom, and those traces can get into the environment through reclaimed water or leaky septic systems.

The researchers found that crayfish exposed to low levels of antidepressant medication behaved more "boldly," emerging from hiding more quickly and spending more time searching for food.

"Crayfish exposed to the antidepressant came out into the open, emerging from their shelter, more quickly than crayfish not exposed to the antidepressant. This change in behavior could put them at greater risk of being eaten by a predator," said Lindsey Reisinger, a co-author of the study and an assistant professor in the UF/IFAS fisheries and aquatic sciences program.

"Crayfish eat algae, dead plants and really anything else at the bottom of streams and ponds. They play an important role in these aquatic environments. If they are getting eaten more often, that can have a ripple effect in those ecosystems," Lindsey Reisinger added.

In their study, conducted while A.J. Reisinger was a postdoctoral researcher at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, the scientists wanted to understand how crayfish respond to low levels of antidepressants in aquatic environments.

"Our study is the first to look at how crayfish respond when exposed to antidepressants at levels typically found in the streams and ponds where they live," A.J. Reisinger said.

The researchers achieved this by recreating crayfish's natural environment in the lab, where they could control the amount of antidepressant in the water and easily observe crayfish behavior.

Crayfish were placed in artificial streams that simulated their natural environment. Some crayfish were exposed to environmentally realistic levels of antidepressant in the water for a few weeks, while a control group was not exposed. The researchers used a common type of antidepressant called a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI.

To test how antidepressant exposure changed crayfish behavior, researchers used something called a Y-maze. This maze has a short entrance that branches into two lanes, like the letter Y.

At the start of the experiment, the researchers placed each crayfish in a container that acted as a shelter, and that shelter was placed at the entrance to the maze.

When researchers opened the shelter, they timed how long it took for the crayfish to emerge. If the crayfish emerged, they had the choice of the two lanes in the Y-maze. One lane emitted chemical cues for food, while the other emitted cues that signaled the presence of another crayfish. The researchers recorded which direction the crayfish chose and how long they spent out of the shelter.

Compared to the control group, crayfish exposed to antidepressants emerged from their shelters earlier and spent more time in pursuit of food. They tended to avoid the crayfish side of the maze, a sign that the levels of antidepressants used in study didn't increase their aggression.

"The study also found that crayfish altered levels of algae and organic matter within the artificial streams, with potential effects on energy and nutrient cycling in those ecosystems," A.J. Reisinger said. "It is likely that the altered crayfish behavior would lead to further impacts on stream ecosystem functions over a longer time period as crayfish continue to behave differently due to the SSRIs. This is something we'd like to explore in future studies."

The study, co-authored with Erinn Richmond of Monash University and Emma Rosi of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, is published in the journal Ecosphere.

Wondering how you can reduce the levels of antidepressants and other pharmaceuticals in water bodies? There are steps people can take, A.J. Reisinger said.

"The answer is not for people to stop using medications prescribed by their doctor. One big way consumers can prevent pharmaceuticals from entering our water bodies is to dispose of medications properly," he said.

INFORMATION:

A.J. Reisinger has authored an Extension publication and infographic on how to dispose of unwanted medications properly and keep them out of water bodies.

Pharmaceutical pollution is found in streams and rivers globally, but little is known about its effects on animals and ecosystems. A new study, published in the journal Ecosphere, investigated the effects of antidepressant pollution on crayfish. Just two weeks of citalopram exposure caused changes in crayfish behavior, with the potential to disrupt stream ecosystem processes like nutrient cycling, oxygen levels, and algal growth.

Coauthor Emma Rosi, a freshwater ecologist at Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, says, "Animals living in streams and rivers are exposed to a chronic mix of pharmaceutical pollution as a result of wastewater contamination. Our study explored how antidepressant levels ...

New Haven, Conn. --In a new study led by Yale Cancer Center, researchers show the nucleoside transporter ENT2 may offer an unexpected path to circumventing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and enabling targeted treatment of brain tumors with a cell-penetrating anti-DNA autoantibody. The study was published today online in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight.

"These findings are very encouraging as the BBB prevents most antibodies from penetrating the central nervous system and limits conventional antibody-based approaches to brain tumors," said James E. Hansen, MD, associate professor of therapeutic radiology, radiation oncology chief of the Yale Gamma Knife Center at Smilow Cancer Hospital, and corresponding author of the study.

Deoxymab-1 (DX1) ...

Ethiopia, Nigeria, Colombia, Myanmar and Syria are just a handful of the places around the world currently engaged in ongoing civil wars. Even when peace agreements can be negotiated to end civil wars, maintaining stability is incredibly challenging. In these fragile post-conflict areas, a small communal dispute can easily escalate and unravel peace deals.

Peacekeepers can help contain the spread of violence and promote peaceful interactions between groups, but how? And in what situations can peacekeepers be most effective? New research from Washington University ...

Changing your eating habits or altering your circadian clock can impact healthy fat tissue throughout your lifespan, according to a preclinical study published today in Nature by researchers with The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth).

Healthy fat tissue helps provide energy, supports cell growth, protects organs, and keeps the body warm. A good quality diet and one that is consumed in a rhythmic manner (i.e., during our active cycle) is important in maintaining healthy fat, the researchers found.

Adipocyte progenitor cells mature into adipocytes - the healthy fat cells that make up our adipose tissue, which stores energy as fat. Researchers discovered that adipocyte progenitors undergo rhythmic daily proliferation throughout the ...

A new model that applies artificial intelligence to carbohydrates improves the understanding of the infection process and could help predict which viruses are likely to spread from animals to humans. This is reported in a recent study led by researchers at the University of Gothenburg.

Carbohydrates participate in nearly all biological processes - yet they are still not well understood. Referred to as glycans, these carbohydrates are crucial to making our body work the way it is supposed to. However, with a frightening frequency, they are also ...

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) have developed two rapid diagnostic tests for COVID-19 that are nearly as accurate as the gold-standard test currently used in laboratories. Unlike the gold standard test, which extracts RNA and uses it to amplify the DNA of the virus, these new tests can detect the presence of the virus in as little as five minutes using different methods.

One test is a COVID-19 molecular diagnostic test, called Antisense, that uses electrochemical sensing to detect the presence of the virus. The other uses a simple assay of gold nanoparticles to detect a color change when the virus is present. Both tests were developed by Dipanjan Pan, PhD, Professor of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine ...

Two new studies have cast unprecedented light on disease processes in tuberculosis, identifying key genetic changes that cause damage in the lungs and a drug treatment that could speed up recovery.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a lung infection that has killed more humans than any other and until last year was the top infectious killer around the world. Globally, an estimated 10 million people develop the disease each year.

The findings are reported in two papers in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

In the first study, a team from the University of Southampton used a new 3D culture system they have developed to observe the changes that occur in cells infected with TB. Unlike the laboratory-standard 2D culture system, where cells are placed ...

This past year has been transformational in terms of not only a global pandemic but a sustained focus on racism and systemic injustice. There has been a widespread circulation of images and videos in the news and online. Just like adults, adolescents are exposed to these images with important consequences for their emotional health and coping. However, few studies have sought to understand the influence of racism experienced online.

According to a qualitative study published in JAMA Network Open adolescents expressed feelings of helplessness when exposed to secondhand racism online. Specifically, adolescents described helplessness stemming from the pervasiveness of racism in our society. This was illustrated by quotes, such as "[racist events are] just another day in the life" referring ...

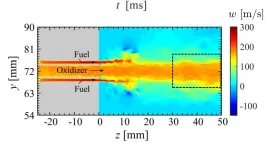

WASHINGTON, June 8, 2021 -- Combustion engines can develop high frequency oscillations, leading to structural damage to the engines and unsafe operating conditions. A detailed understanding of the physical mechanism that causes these oscillations is required but has been lacking until now.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, research from the Tokyo University of Science and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency clarifies the feedback processes that give rise to these oscillations in rocket engines.

The investigators studied simulated combustion events in a computational model of a rocket combustor. Their analysis involved sophisticated techniques, including symbolic ...

For many, the Thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) is little more than a roadside weed, but this plant has a long history with scientists trying to understand how plants grow and develop. Arabidopsis was first scientifically described as early as the 16th century and the first genetic mutant was identified in the 1800s. Since the 1940s, Arabidopsis has increased in popularity within the scientific community, which continues to use it as a model system to explore plant genetics, development and physiology to this day.

One might expect that after decades of scientific scrutiny the structure of Arabidopsis had been fully documented, but a new study from scientists from The Pennsylvania State University, USA, has revealed that this humble plant still has some surprises. The researchers describe ...