(Press-News.org) By repurposing common ingredients in hair conditioner, scientists have designed an inexpensive, transparent coating that can turn surfaces like windows and ceilings into glue pads to trap airborne aerosol droplets. This new strategy is described June 16 in the journal Chem.

"Facing a pandemic, we need to proactively leverage all of the different layers of defense mechanisms, including the physical barriers," says corresponding author Jiaxing Huang, a professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern University. "After all, these viruses must travel through physical space before reaching and eventually infecting people."

The main way that respiratory diseases like COVID-19 spread is from respiratory fluids emitted when an infected person speaks, sneezes, or breathes. These virus-containing fluids include large droplets and fine aerosols that are particularly difficult to control and remove from the air. Upon hitting a surface, the aerosol droplets can bounce off easily and become airborne again.

As a material scientist, Huang wanted to help combat the pandemic in some way. He gathered several researchers in his lab, including Drs. Zhilong Yu and Murat Kadir, and another stay-home student, Yihan Liu, to brainstorm. Eventually, they came up with the idea of turning PAAm-DDA, a polymer commonly used in hair products and cosmetics for locking in the moisture, into a surface coating.

The coating they developed is hydrophilic, so that it can capture incoming pathogen-containing droplets and prevent them from bouncing off surfaces. "There are many indoor environmental surfaces that you barely touch, like parts of the wall closer to the floor and the ceiling," Huang says, where their coating could potentially be applied.

Huang and his team coated a plexiglass divider and tested out its droplet-capture capacity. The team first sprayed a steam of aerosols, generated by a hand-held facial mister, at the barrier to simulate fine respiratory aerosols emitted during speaking. By analyzing the escaped droplets that landed on a silicon wafer, they can estimate how well the coating traps the incoming aerosol droplets. Compared with an uncoated barrier, the coating captured nearly all the aerosols, allowing barely any to escape.

Next, they air-sprayed salt water at the plexiglass to simulate the large droplets released during coughing and sneezing and found that the coating also drastically cut down the number of splashed droplets. In the simulated experiment, the number of droplets that escaped from the plexiglass barrier was reduced by 80%.

In the past, scientists have designed water-trapping agents that mostly target large droplets of water to use in applications such as extracting water from the air in the desert or applications in agriculture. "We did an extensive literature search but didn't really find much work for capturing aerosol droplets. Perhaps there wasn't a strong need for such aerosol-trapping coatings before the pandemic," Huang says.

To make the product applicable to more types of surfaces, the team added another common cosmetic ingredient, called APG, to the coating. They tested it on materials including concrete, wood, metal, glass, and textiles, which are typical surfaces found in indoor spaces. Huang says that more ingredients can be added to give the coating additional functions, such as copper ion as a disinfectant or pigment particles for coloring.

While experiments involving human subjects need to be pre-approved by a few regulatory bodies and are beyond the scope of the study, the team estimated the number of respiratory droplets released by people speaking loudly and continuously in a typical indoor office setting. Their calculation shows that the coating's threshold before becoming saturated with droplets is about 7 to 10 orders of magnitude higher than what would be emitted in the office scenario. In addition, if needed, the coating can be easily wiped off with water and reapplied.

"We understood that the current pandemic may end before this concept is implemented," Huang says. "What we want is to provide scientific evidence for a future public health capacity. It may or may not be used now. But next time, when an outbreak like this happens, I think we will be better equipped."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by a JITRI-Northwestern Research Fellowship awarded from Jiangsu Industrial Technology Research Institute managed by the Northwestern Initiative for Manufacturing Science and Innovation (NIMSI).

Chem, Huang et al.: "Droplet-capturing Coatings on Environmental Surfaces Based on Cosmetic Ingredients" https://www.cell.com/chem/fulltext/S2451-9294(21)00266-7

Chem (@Chem_CP) is the first physical science journal published by Cell Press. A sister journal to Cell, Chem, which is published monthly, provides a home for seminal and insightful research and showcases how fundamental studies in chemistry and its sub-disciplines may help in finding potential solutions to the global challenges of tomorrow. Visit: http://www.cell.com/chem. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact press@cell.com.

Small modeling errors may accumulate faster than previously expected when physicists combine multiple gravitational wave events (such as colliding black holes) to test Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, suggest researchers at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. The findings, published June 16 in the journal iScience, suggest that catalogs with as few as 10 to 30 events with a signal-to-background noise ratio of 20 (which is typical for events used in this type of test) could provide misleading deviations from general relativity, erroneously pointing to new physics where none exists. Because this is close to the size of current catalogs used to assess Einstein's ...

Human babies do even more than we thought while sleeping.

A new study from University of Iowa researchers provides further insights into the coordination that takes place between infants' brains and bodies as they sleep.

The Iowa researchers have for years studied infants' twitching movements during REM sleep and how those twitches contribute to babies' ability to coordinate their bodily movements. In this study, the scientists report that beginning around three months of age, infants see a pronounced increase in twitching during a second major stage of sleep, called quiet sleep.

"This was completely surprising and, for all we know, ...

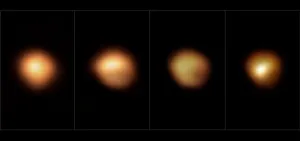

When Betelgeuse, a bright orange star in the constellation of Orion, lost more than two-thirds of its brightness in late 2019 and early 2020, astronomers were puzzled.

What could cause such an abrupt dimming?

Now, in a new paper published Wednesday in Nature, an international team of astronomers reveal two never-before-seen images of the mysterious darkening --and an explanation. The dimming was caused by a dusty veil shading the star, which resulted from a drop in temperature on Betelgeuse's stellar surface.

Led by Miguel Montargès at the Observatoire de Paris, the new images were taken in January and March of 2020 using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope. Combined with images previously taken in ...

EMBARGOED UNTIL 11 A.M. ET WEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 2021

MADISON, Wis. -- Quantum computers could outperform classical computers at many tasks, but only if the errors that are an inevitable part of computational tasks are isolated rather than widespread events. Now, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have found evidence that errors are correlated across an entire superconducting quantum computing chip -- highlighting a problem that must be acknowledged and addressed in the quest for fault-tolerant quantum computers.

The researchers report their findings in a study published June 16 in the journal Nature, Importantly, their work also points to mitigation strategies.

"I think people have been approaching the problem of error correction in an overly optimistic ...

It is possible to re-create a bird's song by reading only its brain activity, shows a first proof-of-concept study from the University of California San Diego. The researchers were able to reproduce the songbird's complex vocalizations down to the pitch, volume and timbre of the original.

Published June 16 in Current Biology, the study lays the foundation for building vocal prostheses for individuals who have lost the ability to speak.

"The current state of the art in communication prosthetics is implantable devices that allow you to generate textual output, writing up to 20 words per minute," said senior author Timothy Gentner, a professor of psychology and neurobiology ...

When Betelgeuse, a bright orange star in the constellation of Orion, became visibly darker in late 2019 and early 2020, the astronomy community was puzzled. A team of astronomers have now published new images of the star's surface, taken using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (ESO's VLT), that clearly show how its brightness changed. The new research reveals that the star was partially concealed by a cloud of dust, a discovery that solves the mystery of the "Great Dimming" of Betelgeuse.

Betelgeuse's dip in brightness -- a change noticeable even to the ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined to what extent cannabis use is associated with thickness in brain areas measured by magnetic resonance imaging in a study of adolescents.

Authors: Matthew D. Albaugh, Ph.D., of the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine in Burlington, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1258)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The ...

What The Study Did: Survival among people with early-onset (diagnosed before age 50) colorectal cancer compared with later-onset colorectal cancer (diagnosed at ages 51 through 55) was compared using data from the National Cancer Database.

Authors: Charles S. Fuchs, M.D., M.P.H., of the Yale School of Public Health in New Haven, Connecticut, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12539)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and ...

What The Study Did: This study demonstrated an association between receiving the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccine and a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers beginning eight days after the first dose.

Authors: Michael E. Charness, M.D., of the VA Boston Healthcare System in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16416)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest ...

A ball of 4,000-year-old hair frozen in time tangled around a whalebone comb led to the first ever reconstruction of an ancient human genome just over a decade ago.

The hair, which was preserved in arctic permafrost in Greenland, was collected in the 1980s and stored at a museum in Denmark. It wasn't until 2010 that evolutionary biologist Professor Eske Willerslev was able to use pioneering shotgun DNA sequencing to reconstruct the genetic history of the hair.

He found it came from a man from the earliest known people to settle in Greenland ...