(Press-News.org) A faster method for collecting pure malaria parasites from infected mosquitos could accelerate the development of new, more potent malaria vaccines.

The new method, developed by a team of researchers led by Imperial College London, enables more parasites to be isolated rapidly with fewer contaminants, which could simultaneously increase both the scalability and efficacy of malaria vaccines.

The parasite that causes malaria is becoming increasingly resistant to antimalarial drugs, with the mosquitoes that transmit the disease also increasingly resistant to pesticides. This has created an urgent need for new ways to fight malaria, which is the world's third-most deadly disease in under-fives, with a child dying from malaria every two minutes.

Existing malaria vaccines that use whole parasites provide moderate protection against the disease. In these vaccines, the parasites are 'attenuated' - just like some flu vaccines and the MMR vaccine - so they infect people and raise a strong immune response that protects against malaria, but don't cause disease themselves.

However, these vaccines require several doses, with each dose requiring potentially tens of thousands of parasites at an early stage of their development, known as sporozoites. Sporozoites are normally found in the salivary glands of mosquitoes, and in a natural infection are passed to humans when the mosquito bites. They then travel to the human liver, where they prepare to cause infection in the body.

Extracting sporozoites for use in a live vaccine currently requires manual dissection of the mosquito salivary glands - miniscule structures behind the mosquito head - by a skilled technician, which is a time-consuming and costly process.

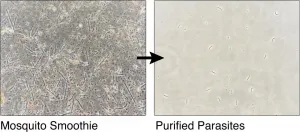

The new method, described today in Life Science Alliance, vastly speeds up this process by effectively creating a 'mosquito smoothie' and then filtering the resulting liquid by size, density and electrical charge, leaving a pure sporozoite product suitable for vaccination. Importantly, no dissection is required.

Lead researcher Professor Jake Baum, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: "Creating whole-parasites vaccines in large enough volumes and in a timely and cost-effective way has been a major roadblock for advancing malaria vaccinology, unless you can employ an army of skilled mosquito dissectors. Our new method presents a way to radically cheapen, speed up and improve vaccine production."

But it's not just about speed and cost. Traditional dissection methods struggle to remove all contaminants, such as proteins from the salivary glands, which are often extracted with sporozoites. The extra debris is likely to affect the infectivity of the sporozoites once they are inside the body, and could even affect how the immune system responds, impacting the efficacy of any whole parasite vaccine.

The new method also tackles this problem, resulting in pure uncontaminated sporozoite samples. The team discovered that, as well as being purer, sporozoites produced were surprisingly more infectious, hinting that vaccines produced using their method may require a much lower dose of sporozoites.

First author of the study Dr Joshua Blight, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: "With this new approach we not only improve the scalability of vaccine production, but our isolated sporozoites may actually prove to be more potent as a vaccine, giving us additional bang per mosquito buck."

The team developed and tested their method with both human and rodent malaria parasites. They then tested the rodent version as a vaccine in mice, and found that when exposed to an infected mosquito bite, vaccinated mice showed 60-70 per cent protection when immunisations were given into muscle. When the same sporozoites were given directly into the blood stream (intravenously) protection was 100 per cent, known as 'sterile' protection.

The researchers are now developing the method further in readiness for mass manufacture of sporozoites under good manufacturing practice (GMP) conditions in order to produce a vaccine ready for human challenge trials. The plan is that participants would be given vaccine-grade sporozoites produced using this method and then purposefully bitten by an infected mosquito.

Looking beyond vaccines the researchers also say their method should help accelerate studies of sporozoite biology in general, which could in turn lead to fresh insights into the liver stage of malaria and new drug and vaccine regimes.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Ibaraki, Japan - Severe childhood restrictive cardiomyopathy is a condition that causes the muscles in the walls of the heart to become stiff, so that the heart is unable to fill properly with blood. A mutation in a protein called BAG3 is known to result in restrictive cardiomyopathy, muscle weakness, difficulty taking in enough oxygen, and damage to multiple peripheral nerves, often shortening the patient's lifespan significantly. Until now there has been no successful model for the disease, making it extremely difficult to study.

However, researchers in Japan and Germany have now created a mouse model that mimics the human pathology, allowing the disease to be studied more easily. The team's data suggest ...

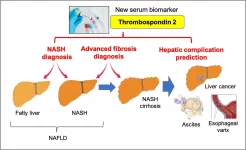

Osaka, Japan - Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease worldwide and can progress to liver cirrhosis, liver failure or cancer. Currently, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) diagnosis requires an invasive liver biopsy which can lead to procedural complications. Now, researchers at Osaka University working with international collaborators have identified a noninvasive biomarker that can identify patients at risk of NAFLD complications using a simple blood test.

Owing to the increasing prevalence of obesity worldwide, ...

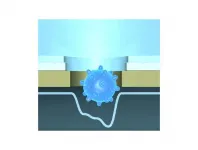

The electroreduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) to produce value-added multicarbon compounds is an effective way to cut down CO2 emission. However, the low solubility of CO2 largely limits the application of related technology.

Although gas diffusion electrode (GDE) can accelerate the reaction rate, the instability of the catalysts caused by electrolyte flooding hinders further reaction.

Recently, inspired by setaria's hydrophobic leaves, Prof. GAO Minrui's team from University of Science and Technology of China developed Cu catalyst composed of sharp needles which possesses high level ...

When animals are hot, they eat less. This potentially fatal phenomenon has been largely overlooked in wild animals, explain researchers from The Australian National University (ANU).

According to lead author Dr Kara Youngentob, it means climate change could be contributing to more deaths among Australia's iconic marsupials, like the greater glider, than previously thought.

"Hot weather puts all animals off their food. Humans can deal with it fairly well; we usually have plenty of fat reserves and lots of different ...

A destructive pest beetle is edging closer to Australia as biological controls fail, destroying home gardens, plantations and biodiversity as they surge through nearby Pacific islands.

University of Queensland researcher Dr Kayvan Etebari has been studying how palm-loving coconut rhinoceros beetles have been accelerating their invasion.

"We thought we'd outsmarted them," Dr Etebari said.

"In the 1970s, scientists from Australia and elsewhere found that coconut rhinoceros beetles could be controlled with a beetle virus from Malaysia.

"This virus stopped the beetle in its tracks and, for the last 50 years or so, it more-or-less stayed put ...

As demand for electricity rises and climate change brings more frequent and extreme storms, residents in rural and suburban communities must have access to the minimal electricity they need to survive a large, long-duration (LLD) power outage.

A new study in the journal Risk Analysis compared strategies for providing emergency power to residents in two hypothetical New England communities during such an event. The results suggest that cooperative strategies like sharing a higher capacity generator among multiple homes cost 10 to 40 times less than if each household used its own generator.

"Our findings provide impetus for utilities, regulators, ...

Osaka, Japan - A team of scientists headed by SANKEN (The Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research) at Osaka University demonstrated that single virus particles passing through a nanopore could be accurately identified using machine learning. The test platform they created was so sensitive that the coronaviruses responsible for the common cold, SARS, MERS, and COVID could be distinguished from each other. This work may lead to rapid, portable, and accurate screening tests for COVID and other viral diseases.

The global coronavirus pandemic has revealed the ...

[Background]

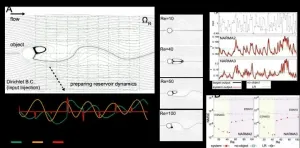

In recent years, physical reservoir computing*1), one of the new information processing technologies, has attracted much attention. This is a physical implementation version of reservoir computing, which is a learning method derived from recurrent neural network (RNN)*2) theory. It implements computation by regarding the physical system as a huge RNN, outsourcing the main operations to the dynamics of the physical system that forms the physical reservoir. It has the advantage of obtaining optimization instantaneously with limited computational resources by adjusting linear and static readout weightings between the output and a physical reservoir without requiring optimization of the weightings by back propagation. However, since the information processing capability depends ...

SINGAPORE, 17 June 2021 - New details on the structure and function of a transport protein could help researchers develop drugs for neurological diseases that are better able to cross the blood-brain barrier. The findings were published in the journal Nature by researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Duke-NUS Medical School, Weill Cornell Medicine and colleagues.

Omega-3 fatty acids, like docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are important for brain and eye development. They are derived mainly from dietary sources and converted ...

New research presents over 300 new analyses of bronze objects, raising the total number to 550 in 'the archaeological fingerprint project'. This is roughly two thirds of the entire metal inventory of the early Bronze Age in southern Scandinavia. For the first time, it was possible to map the trade networks for metals and to identify changes in the supply routes, coinciding with other socio-economic changes detectable in the rich metal-dependent societies of Bronze Age southern Scandinavia.

The magnificent Bronze Age in southern Scandinavia rose from copper traded from the British Isles and Slovakia 4000 years ago. 500 ...