Long-term Himalayan glacier sStudy

Heidelberg University geographers combine historical images and maps with current data

2021-06-17

(Press-News.org) The glaciers of Nanga Parbat - one of the highest mountains in the world - have been shrinking slightly but continually since the 1930s. This loss in surface area is evidenced by a long-term study conducted by researchers from the South Asia Institute of Heidelberg University. The geographers combined historical photographs, surveys, and topographical maps with current data, which allowed them to show glacial changes for this massif in the north-western Himalaya as far back as the mid-1800s.

Detailed long-term glacier studies that extend the observation period to the time before the ubiquitous availability of satellite data are barely possible in the Himalayan region due to the dearth of historical data. As Prof. Dr Marcus Nüsser from the South Asia Institute explains, this is not the case for the Nanga Parbat Massif. The earliest documents include sketch maps and drawings made during a research expedition in 1856. Based on this historical data, the Heidelberg researchers reconstructed the glacier changes along the South Face of Nanga Parbat. Additionally, there are numerous photographs and topographical maps stemming from climbing and scientific expeditions since 1934. Some of these historical photographs were retaken in the 1990s and 2010s from identical vantage points for the purpose of comparison. Satellite images dating back to the 1960s completed the data base Prof. Nüsser and his team used to create a multi-media temporal analysis and quantify glacier changes.

The Nanga Parbat glaciers largely fed by ice and snow avalanches show significantly lower retreat rates than other Himalayan regions. One exception is the mainly snow-fed Rupal Glacier, whose retreat rate is significantly higher. "Overall, more studies are needed to better understand the special influence of avalanche activity on glacier dynamics in this extreme high mountain region," states Prof. Nüsser.

The researchers are particularly interested in glacier fluctuations, changes in ice volume, and the increase of debris-covered areas on the glacier surfaces. Their analyses covered 63 glaciers already documented in 1934. "The analyses showed that the ice-covered area decreased by approximately seven percent, and three glaciers disappeared completely. At the same time we identified a significant increase in debris coverage," adds Prof. Nüsser. The geographical location of the Nanga Parbat Massif in the extreme northwest of the Himalayan arc near the Karakorum range could play a particular role in the comparatively moderate glacier retreat. In the phenomenon known as the Karakorum anomaly, no major glacier retreat has been identified as a result of climate change in this mountain range - as opposed to everywhere else in the world. "An increase in precipitation at high altitudes may be the reason, but the exact causes are still unknown," explains Prof. Nüsser. The researchers assume that the low ice losses in the Karakorum and the Nanga Parbat region may also be due to the protection offered by the massive debris-cover and a year-round avalanche flow from the steep flanks.

INFORMATION:

The study shows the major potential of integrating historical material with terrestrial photography and remote sensing imagery to reconstruct glacier development over extended time periods, which is required for making the effects of global climate change visible.

The German Research Foundation funded the field work for this project. The results were published in the journal "Science of the Total Environment". The photographic data material is available from the open-access journal "Data in Brief".

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-17

DALLAS, June 16, 2021 -- Findings from a small study detailing the treatment of myocarditis-like symptoms in seven people after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S. are published today in the American Heart Association's flagship journal Circulation. These cases are among those reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) documenting the development of myocarditis-like symptoms in some people who received the COVID-19 vaccine.

Myocarditis is a rare but serious condition that causes inflammation of the middle layer of the wall of the heart muscle. It can weaken the heart and affect the heart's electrical system, which keeps the heart pumping regularly. It is most often the result of an infection and/or ...

2021-06-17

They're cute, they're furry, and they start diving into frigid Antarctic waters at 2 weeks old. According to a new study from California Polytechnic State University, Weddell seal pups may be one of the only types of seals to learn to swim from their mothers.

Weddell seals are the southernmost born mammal and come into the world in the coldest environment of any mammal. These extreme conditions may explain the unusually long time they spend with their mothers.

The study, "Early Diving Behavior in Weddell Seal (Leptonychotes Weddellii) Pups," was published earlier this month in the Journal of Mammalogy.

According to the Seal Conservation Society, adult Weddell seal females are ...

2021-06-17

Once thought to be extinct, lobe-finned coelacanths are enormous fish that live deep in the ocean. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on June 17 have evidence that, in addition to their impressive size, coelacanths also can live for an impressively long time--perhaps nearly a century.

The researchers found that their oldest specimen was 84 years old. They also report that coelacanths live life extremely slowly in other ways, reaching maturity around the age of 55 and gestating their offspring for five years.

"Our most important finding is that the coelacanth's age was underestimated by a factor of five," says Kélig Mahé of IFREMER Channel and North ...

2021-06-17

The birth of a human being requires billions of cell divisions to go from a fertilised egg to a baby. At each of these divisions, the genetic material of the mother cell duplicates itself to be equally distributed between the two new cells. In primary microcephaly, a rare but serious genetic disease, the ballet of cell division is dysregulated, preventing proper brain development. Scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), in collaboration with Chinese scientists, have demonstrated how the mutation of a single protein, WDR62, prevents the proper formation of the cable network responsible for separating genetic material into two. As cell division is then slowed down, the brain ...

2021-06-17

BOSTON - An antibiotic developed in the 1950s and largely supplanted by newer drugs, effectively targets and kills cancer cells with a common genetic defect, laboratory research by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute scientists shows. The findings have spurred investigators to open a clinical trial of the drug, novobiocin, for patients whose tumors carry the abnormality.

In a study in the journal Nature Cancer, the researchers found that in laboratory cell lines and tumor models novobiocin selectively killed tumor cells with abnormal BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, which help repair damaged DNA. The drug was effective even in tumors resistant to agents known as PARP inhibitors, which have become a prime therapy for cancers with DNA-repair glitches.

"PARP inhibitors ...

2021-06-17

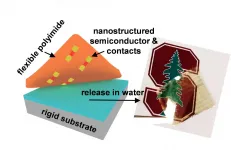

Ultrathin, flexible computer circuits have been an engineering goal for years, but technical hurdles have prevented the degree of miniaturization necessary to achieve high performance. Now, researchers at Stanford University have invented a manufacturing technique that yields flexible, atomically thin transistors less than 100 nanometers in length - several times smaller than previously possible. The technique is detailed in a paper published June 17 in Nature Electronics.

With the advance, said the researchers, so-called "flextronics" move closer to reality. Flexible electronics promise bendable, ...

2021-06-17

PHILADELPHIA-- The COVID-19 death rate for Black patients would be 10 percent lower if they had access to the same hospitals as white patients, a new study shows. Researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and OptumLabs, part of UnitedHealth Group, analyzed data from tens of thousands of hospitalized COVID-19 patients and found that Black patients died at higher rates than white patients. But the study, published today in JAMA Network Open, determined that didn't have to be the case if more Black patients were able to get care at different hospitals.

"Our study reveals that Black patients have worse outcomes largely because they tend to go to worse-performing hospitals," said the study's first author, David Asch, MD, ...

2021-06-17

What The Study Did: The findings of this study suggest that the increased mortality among Black patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is associated with the hospitals at which Black patients disproportionately received care.

Authors: David A. Asch, M.D., M.B.A., of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12842)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, ...

2021-06-17

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated the association of convalescent plasma treatment with 30-day mortality in hospitalized adults with hematologic (blood) cancers and COVID-19.

Authors: Jeremy L.Warner, M.D., M.S., of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1799)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please ...

2021-06-17

What The Study Did: This study examined whether mandatory daily employee symptom data collection can be used as an early alert surveillance system to estimate COVID-19 hospitalizations in communities where employees live.

Authors: Steven Horng, M.D., M.MSc., of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, is the the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13782)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Long-term Himalayan glacier sStudy

Heidelberg University geographers combine historical images and maps with current data