(Press-News.org) Today as they did 100 years ago, doctors diagnose cancer by taking tissue samples from patients, which they usually fix in formalin for microscopic examination. In the past 20 years, genetic methods have also been established that make it possible to characterize mutations in tumors in greater detail, thus helping clinicians select the best treatment strategy.

Even tiny tissue samples can be used to detect proteins

Now, a group of researchers from the Berlin-based Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH), Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) have succeeded in analyzing in detail more than 8,000 proteins in fixed samples of lung cancer tissue using mass spectrometers.

"Using the methods we have developed, it has become possible to conduct an in-depth analysis of molecular processes in cancer cells at the protein level - and to do so in archived patient samples that are collected and stored in large numbers in everyday clinical practice," says Dr. Philipp Mertins, head of the Proteomics Platform at the MDC and the BIH. "Even very small tissue samples, such as those obtained in needle biopsies, are sufficient for our experiments."

The study, published in the journal "Nature Communications", is considered a major success for the Multimodal Clinical Mass Spectrometry to Target Treatment Resistance (MSTARS) research project, which has been funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) to the tune of around €5.7 million since 2020.

The team of researchers, led by Mertins and Professor Frederick Klauschen from the Institute of Pathology at Charité, has been able to show that proteins - unlike the frequently studied yet quite sensitive RNA molecules - remain stable in the samples for many years and can be precisely quantified. "In addition, the proteins that are present in the tumor tissue map disease progression especially well," says lead author Corinna Friedrich, a PhD student in the labs of Mertins and Klauschen. "This is because they provide information about such things as which of the genes that promote or inhibit tumor growth are particularly active in the cells."

The methods promise to help identify the best treatment for each tumor

The picture gained from the team's analysis of two forms of lung cancer - adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas - has also become so detailed because the researchers have not only uncovered a great many of the proteins present in the cell, but have also quantified more than 14,000 phosphosites. With the help of phosphorylation, a mechanism that regulates the reversible attachment of phosphate groups to proteins, the cell controls almost all biological processes by switching certain signaling pathways on or off.

"Our paper thus provides a good basis for gaining a better understanding of disease progression in lung cancer and also in other types of cancer," says Klauschen, who, along with Mertins, is co-corresponding author of the study. Klauschen has since become director of the Institute of Pathology at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, but continues to conduct research at Charité. "The methods we have developed will also enable us to better explain in the future why a very specific therapy works for some patients but not for others," adds the pathologist. This will, he says, make it easier, to find the best treatment option for each patient.

Methods also suitable for researching cardiovascular diseases

Mertins also hopes that the mass spectrometric analysis of the proteome in tissue samples will pave the way for the discovery of not only new biomarkers for therapeutic decisions and patient survival predictions, but also other molecular structures that could serve as targets for future drugs.

And, according to the researcher, there is yet another plus to the new approach: "Our methods are not only suitable for researching cancer, but can also be applied very broadly." For example, the Proteomics Platform has already successfully analyzed the proteome of fixed immune cells from COVID-19 patients. The authors have also provided guidelines on which mass spectrometric methods are best suited for different types of clinical studies.

Next on the agenda for the MDC platform is the mass spectrometric analysis of additional fixed immune cells as well as fixed cardiovascular tissue for the presence of proteins and phosphosites. "The aim here is to get a better understanding of infectious and cardiovascular diseases," explains Mertins, "so that one day it might be possible to treat these diseases in a much better way than has so far been the case."

INFORMATION:

Scientific contacts:

Dr. Philipp Mertins

Proteomics Platform

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

Tel.: +49 30 9406-3521

philipp.mertins@mdc-berlin.de

http://www.mdc-berlin.de/proteomics

Professor Dr. Frederick Klauschen

Institute of Pathology

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU)

Tel.: +49 89 2180-73602

frederick.klauschen@med.uni-muenchen.de

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) is one of the world's leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the MDC's locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 60 countries analyze the human system - investigating the biological foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium in a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. The MDC therefore supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the MDC today employs 1,600 people and is funded 90 percent by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin. http://www.mdc-berlin.de

The German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina and the German Council for Sustainable Development (RNE) have published a joint position paper presenting paths to climate neutrality by 2050. In it, the Leopoldina and the RNE highlight options for action to effect the changes needed within society, at political level and in the business world, in view especially of the urgency and the historic dimensions of the transformation we face. With the paper, the Leopoldina and the RNE are consciously not seeking to engage in a race to set the most ambitious target. They are instead offering an options paper for setting the right course and covering the key implementation steps. ...

Abu Dhabi, UAE: Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs), small objects that orbit the sun beyond Neptune, are fossils from the early days of the solar system which can tell us a lot about its formation and evolution.

A new study led by Mohamad Ali-Dib, a research scientist at the NYU Abu Dhabi END ...

Chemical engineers at the University of Illinois Chicago and UCLA have answered longstanding questions about the underlying processes that determine the life cycle of liquid foams. The breakthrough could help improve the commercial production and application of foams in a broad range of industries.

Findings of the END ...

The glaciers of Nanga Parbat - one of the highest mountains in the world - have been shrinking slightly but continually since the 1930s. This loss in surface area is evidenced by a long-term study conducted by researchers from the South Asia Institute of Heidelberg University. The geographers combined historical photographs, surveys, and topographical maps with current data, which allowed them to show glacial changes for this massif in the north-western Himalaya as far back as the mid-1800s.

Detailed long-term glacier studies that extend the observation period ...

DALLAS, June 16, 2021 -- Findings from a small study detailing the treatment of myocarditis-like symptoms in seven people after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S. are published today in the American Heart Association's flagship journal Circulation. These cases are among those reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) documenting the development of myocarditis-like symptoms in some people who received the COVID-19 vaccine.

Myocarditis is a rare but serious condition that causes inflammation of the middle layer of the wall of the heart muscle. It can weaken the heart and affect the heart's electrical system, which keeps the heart pumping regularly. It is most often the result of an infection and/or ...

They're cute, they're furry, and they start diving into frigid Antarctic waters at 2 weeks old. According to a new study from California Polytechnic State University, Weddell seal pups may be one of the only types of seals to learn to swim from their mothers.

Weddell seals are the southernmost born mammal and come into the world in the coldest environment of any mammal. These extreme conditions may explain the unusually long time they spend with their mothers.

The study, "Early Diving Behavior in Weddell Seal (Leptonychotes Weddellii) Pups," was published earlier this month in the Journal of Mammalogy.

According to the Seal Conservation Society, adult Weddell seal females are ...

Once thought to be extinct, lobe-finned coelacanths are enormous fish that live deep in the ocean. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on June 17 have evidence that, in addition to their impressive size, coelacanths also can live for an impressively long time--perhaps nearly a century.

The researchers found that their oldest specimen was 84 years old. They also report that coelacanths live life extremely slowly in other ways, reaching maturity around the age of 55 and gestating their offspring for five years.

"Our most important finding is that the coelacanth's age was underestimated by a factor of five," says Kélig Mahé of IFREMER Channel and North ...

The birth of a human being requires billions of cell divisions to go from a fertilised egg to a baby. At each of these divisions, the genetic material of the mother cell duplicates itself to be equally distributed between the two new cells. In primary microcephaly, a rare but serious genetic disease, the ballet of cell division is dysregulated, preventing proper brain development. Scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), in collaboration with Chinese scientists, have demonstrated how the mutation of a single protein, WDR62, prevents the proper formation of the cable network responsible for separating genetic material into two. As cell division is then slowed down, the brain ...

BOSTON - An antibiotic developed in the 1950s and largely supplanted by newer drugs, effectively targets and kills cancer cells with a common genetic defect, laboratory research by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute scientists shows. The findings have spurred investigators to open a clinical trial of the drug, novobiocin, for patients whose tumors carry the abnormality.

In a study in the journal Nature Cancer, the researchers found that in laboratory cell lines and tumor models novobiocin selectively killed tumor cells with abnormal BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, which help repair damaged DNA. The drug was effective even in tumors resistant to agents known as PARP inhibitors, which have become a prime therapy for cancers with DNA-repair glitches.

"PARP inhibitors ...

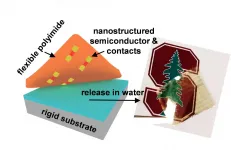

Ultrathin, flexible computer circuits have been an engineering goal for years, but technical hurdles have prevented the degree of miniaturization necessary to achieve high performance. Now, researchers at Stanford University have invented a manufacturing technique that yields flexible, atomically thin transistors less than 100 nanometers in length - several times smaller than previously possible. The technique is detailed in a paper published June 17 in Nature Electronics.

With the advance, said the researchers, so-called "flextronics" move closer to reality. Flexible electronics promise bendable, ...