Nature article: Dieting and its effect on the gut microbiome

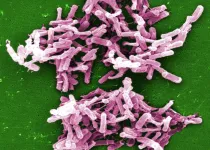

Bacterium associated with antibiotic-induced colitis plays a role in weight control

2021-06-23

(Press-News.org) Researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the University of California in San Francisco were able to show for the first time that a very low calorie diet significantly alters the composition of the microbiota present in the human gut. In a current Nature* publication, the researchers report that dieting results in an increase of specific bacteria - notably Clostridioides difficile, which is associated with antibiotic-induced diarrhea and colitis. These bacteria apparently affect the body's energy balance by exerting an influence on the absorption of nutrients from the gut.

The human gut microbiome consists of trillions of microorganisms and differs from one person to the next. In persons who are overweight or obese, for instance, its composition is known to be different to that found in individuals with a normal body weight. Many of us will, at some point in our lives, try dieting in order to lose weight. But what effect does such a drastic change in diet have on our bodies? An international team of researchers co-led by Charité has addressed this question. "For the first time, we were able to show that a very low calorie diet produces major changes in the composition of the gut microbiome and that these changes have an impact on the host's energy balance," says Prof. Dr. Joachim Spranger, Head of Charité's Department of Endocrinology and Metabolic Diseases and one of the study's lead authors.

To explore the effects of dieting, the team studied 80 older (post-menopausal) women whose weight ranged from slightly overweight to severely obese for a duration of 16 weeks. The women either followed a medically supervised meal replacement regime, consuming shakes totaling less than 800 calories a day, or maintained their weight for the duration of the study. The participants were examined at the Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), a facility jointly operated by Charité and the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC). Regular stool sample analysis showed that dieting reduced the number of microorganisms present in the gut and changed the composition of the gut microbiome. "We were able to observe how the bacteria adapted their metabolism in order to absorb more sugar molecules and, by doing so, make them unavailable to their human host. One might say we observed the development of a 'hungry microbiome'," says the study's first author, Dr. Reiner Jumpertz von Schwartzenberg, a researcher and clinician at the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolic Diseases whose work on the study was funded by the Clinician Scientist program operated by Charité and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH).

Stool samples, which had been collected before and after dieting, were then transferred into mice which had been kept under germ-free conditions and, as a result, lacked all gut microbiota. The results were staggering: Animals which received post-dieting stools lost more than 10 percent of their body mass. Pre-diet stools had no effect whatsoever. "Our results show that this phenomenon is primarily explained by changes in the absorption of nutrients from the animals' guts," says Prof. Spranger. He adds: "This highlights the fact that gut bacteria have a major impact on the absorption of food."

When the researchers studied stool composition in greater detail, they were particularly struck by signs of increased colonization by a specific bacterium - Clostridioides difficile. While this microorganism is commonly found in the natural environment and in the guts of healthy human beings and animals, its numbers in the gut can increase in response to antibiotic use, potentially resulting in severe inflammation of the gut wall. It is also known as one of the most common hospital-associated pathogens. Increased quantities of the bacterium were found both in participants who had completed the weight loss regimen and in mice which had received post-dieting gut bacteria. "We were able to show that C. difficile produced the toxins typically associated with this bacterium and that this was what the animals' weight loss was contingent upon," explains Prof. Spranger. He adds: "Despite that, neither the participants nor the animals showed relevant signs of gut inflammation."

Summing up the results of the research, Prof. Spranger says: "A very low calorie diet severely modifies our gut microbiome and appears to reduce the colonization-resistance for the hospital-associated bacterium Clostridioides difficile. These changes render the absorption of nutrients across the gut wall less efficient, notably without producing relevant clinical symptoms. What remains unclear is whether or to which extent this type of asymptomatic colonization by C. difficile might impair or potentially improve a person's health. This has to be explored in larger studies." Results from the current study, which also received funding from the German Center for Cardiovascular Disease (DZHK), might even give rise to treatment options for metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes. For this reason, the researchers will now explore how gut bacteria might be influenced in order to produce beneficial effects on the weight and metabolism of their human hosts.

INFORMATION:

*Jumpertz von Schwartzenberg R et al. Caloric restriction disrupts the microbiota and colonization resistance. Nature (2021), doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03663-4.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-23

WHAT:

National Institutes of Health scientists and their collaborators have identified an internal communication network in mammals that may regulate tissue repair and inflammation, providing new insights on how diseases such as obesity and inflammatory skin disorders develop. The new research is published in Cell.

The billions of organisms living on body surfaces such as the skin of mammals--collectively called microbiota--communicate with each other and the host immune system in a sophisticated network. According to the study, viruses integrated in the host genome, remnants of previous infections called endogenous retroviruses, can ...

2021-06-23

Researchers at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science and the RIKEN BioResource Research Center in Japan, along with collaborators at the State University of New York at Buffalo, have created a mouse model that allows the study of naturally occurring melatonin. Published in the Journal of Pineal Research, these first experiments using the new mice showed that natural melatonin was linked to a pre-hibernation state that allows mice to slow down their metabolism and survive when food is scarce, or temperatures are cold.

Melatonin is called "the hormone of darkness" because it's released by the brain in the dark, which usually means at night. It tells the body when it's dark outside so that the body can switch to 'night mode'. Although other hormones are easily studied in the laboratory, ...

2021-06-23

How many tree species are there in the forest? How are the trees scattered throughout? How high are the individual tree crowns? Are there fallen trees or hollowed-out tree trunks? Forest scientists characterize forests according to structural factors. "Structural richness is very important for biodiversity in forests. But forests used for forestry are generally poor in terms of structure," says Tristan Eckerter from the Chair of Nature Conservation and Landscape Ecology at the University of Freiburg. Therefore, together with research teams from the Chair of Silviculture and the Black Forest National Park, he investigated ...

2021-06-23

A new article published in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research presents a neural model of maladaptive consumption.

Consumption (of, for instance, substances, food, and online media) is driven mainly by expected rewards that stem from the ability of the consumption act to satisfy intrinsic (e.g., curiosity) and extrinsic (e.g., job performance) needs. In the article, "A Triple-System Neural Model of Maladaptive Consumption," the authors define maladaptive consumption as a state of compulsive seeking and consumption of rewarding products or experiences, which are sustained despite the negative consequences of such behaviors.

"Understanding the neural basis of maladaptive ...

2021-06-23

Pairing blueberry pie with a scoop of ice cream is a nice summer treat. Aside from being tasty, this combination might also help people take up more of the "superfruit's" nutrients, such as anthocyanins. Researchers reporting in ACS' Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry show that α-casein, a protein found in cow's milk, helped rats absorb more blueberry anthocyanins and their byproducts, boosting accessibility to these good-for-you nutrients.

In studies, anthocyanins have been shown to have antioxidant properties, lower blood pressure and reduce the risk of developing some cancers. However, only small amounts of these nutrients are absorbed ...

2021-06-23

For patients who have inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS), the condition is literally a pain in the gut. Chronic -- or long-term -- abdominal pain is common, and there are currently no effective treatment options for this debilitating symptom. In a new study in ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, researchers identify a new potential source of relief: a molecule derived from spider venom. In experiments with mice, they found that one dose could stop symptoms associated with IBS pain.

The sensation of pain originates in electrical signals carried from the body to the brain by cells called ...

2021-06-23

Air quality varies greatly within regions and cities around the world, and exposure to air pollution can have severe health impacts. In the U.S., people of color are disproportionately exposed to poor air quality. A cover story in Chemical & Engineering News, the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society, highlights how scientists and community activists are using new technologies to gather data that could help address this inequity.

Despite the success of the U.S. Clean Air Act in improving ambient air quality over the past 50 years, discriminatory housing, loan ...

2021-06-23

Over recent years, the retina has established its position as one of the most promising biomarkers for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer's. Moving on from the debate as to the retina becoming thinner or thicker, researchers from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and Hospital Clínico San Carlos are focusing their attention on the roughness of the ten retinal layers.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, "proves innovative" in three aspects according to José Manuel Ramírez, Director of the IIORC (Ramón Castroviejo Institute of Ophthalmologic Research) at the UCM. "This is the first study to propose studying the roughness of the retina and its ten constituent layers. They have devised a mathematical method to measure the degree of wrinkling, through the fractal ...

2021-06-23

Children with obstructive sleep apnea are nearly three times more likely to develop high blood pressure when they become teenagers than children who never experience sleep apnea, according to a new study funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health. However, children whose sleep apnea improves as they grow into adolescence do not show an increased chance of having high blood pressure, which is a major risk factor for heart disease.

The long-term study, one of the largest of its kind in the pediatric population, underscores the seriousness of sleep apnea in children and the importance of early treatment, the researchers said. Their findings appear online in the journal JAMA Cardiology.

Obstructive sleep apnea, ...

2021-06-23

Previous research was falsely reassuring; captured only 2% of cirrhosis patients

Findings underscore lack of access to health care for Black patients

Cirrhosis is leading cause of death and affects more than 600,000 people in U.S.

CHICAGO --- Black patients with cirrhosis - late-stage liver disease - are about 25% more likely to die compared to non-Hispanic white patients and four times less likely to receive a liver transplant, reports a new Northwestern Medicine study.

Estimates of racial disparity in cirrhosis have been limited by a lack of large-scale longitudinal data, which track patients from diagnosis to death and/or transplant.

The paper is one of the first to link all seven large liver centers in Chicago with the death registry and transplant registry to examine ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Nature article: Dieting and its effect on the gut microbiome

Bacterium associated with antibiotic-induced colitis plays a role in weight control