(Press-News.org) The rarity of these syndromes, caused by damage to a gene named HUWE1, means very few children are affected. Of course, the low absolute numbers are little consolation for children who are born with a severe intellectual disability as a result of gene mutation.

Many affected children have distinctive facial features, some struggle to learn to walk, and many never learn to speak. Some have an abnormally small head and have stunted growth.

There is no cure. Parents mainly focus on learning enough about how to cope to make everyday life workable.

A lot of parents struggle with guilt. Why did their child turn out like this? Could it be their fault?

Marte Gjøl Haug is the senior consultant in medical genetics at St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim, Norway, and has met with many despairing parents.

In recent years, the number of referrals has increased significantly as genetic testing has become cheaper and more readily available.

"Many parents are afraid that the cause of their child's condition stems from something they could have avoided. A lot of parents have thought this for years before the child is referred and given a genetic diagnosis, which often adds an extra burden to their situation. Once they know that damage to a gene is the cause, many of them are hugely relieved. It wasn't the one glass of wine during the pregnancy that was the cause after all," says Haug.

The problems that result from the damaged HUWE1 gene have names like Juberg-Marsidi, Say-Meyer or Brooks syndrome.

The gene in question is one of more than 900 found on the X chromosome, the female sex chromosome. Girls have two X chromosomes. Boys have an X chromosome and a Y chromosome. Syndromes that are associated with the X chromosome, such as HUWE1, can therefore have differing degrees of severity in both girls and boys.

The damage to the gene occurs when a mutation occurs.

All genes have to be copied, but in instances when DNA fails to copy accurately, a mutation results that can lead to a number of diseases.

Damage to HUWE1 is known to lead to various syndromes, but this is the first time that anyone has figured out that all of the different syndromes have a common cause.

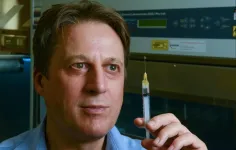

Professor Barbara van Loon is the researcher behind the discovery. She is a graduate of MIT and the University of Zurich, and came to NTNU, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, from Switzerland. Her expertise is in the field of DNA repair.

Studying these syndromes is challenging because the number of individuals affected by each syndrome is very low.

The low number makes it difficult for researchers to obtain a large enough number of samples to be able to draw conclusions.

"Individually, many of the syndromes are rare, but a lot of people are affected if you combine all the rare syndromes," says van Loon.

Van Loon obtained blood cells from five boys with rare syndromes. In this way, she gathered enough genetic material to find a link.

To recreate the development of the disease, she created stem cells from skin cells from a child with a rare syndrome, and cultured mini-brains of these cells.

Her research allowed her to see that the cause of the syndromes was a protein called p53. This protein plays a major role in very basic neurological mechanisms.

If p53 gets out of control, a cell can develop into a cancer cell. It is well known that this gene is important in the development of cancer. Now, for the first time, van Loon and her colleagues have documented that it can also lead to such great problems with the brain's development to cause intellectual disabilities.

"Our findings don't mean that we can come up with a quick cure, but being able to explain the very basic mechanisms behind an illness is an important prerequisite for developing diagnostics and serving as a basis for future treatment. It's also important in itself to give the affected families more information about the disease and how it's developed," says van Loon.

Barbara van Loon works on basic research, which focuses on the very basic and fundamental processes in human beings. Her research is driven by the goal to discover completely new cell connections.

Van Loon's research findings are important pieces in the large puzzles that could result in a future breakthrough in how disease should be treated.

Knowledge gained through basic research is the most important source of major breakthroughs in medical treatment, but it can be years between a basic research discovery and clinical applications.

INFORMATION:

Reference: Aprigliano R, Aksu ME, Bradamante S, Mihaljevic B, Wang W, Rian K, Montaldo NP, Grooms KM, Fordyce Martin SL, Bordin DL, Bosshard M, Peng Y, Alexov E, Skinner C, Liabakk NB, Sullivan GJ, Bjørås M, Schwartz CE, van Loon B. Increased p53 signaling impairs neural differentiation in HUWE1-promoted intellectual disabilities. Cell Rep Med. 2021 Apr 8;2(4):100240. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100240.

A study from the Centre for Nutraceuticals at the University of Westminster found that plant-based protein shakes may be potential viable alternatives to milk-based whey protein shakes, particularly in people with need of careful monitoring of glucose levels.

The study, published in the journal Nutrients, is the first to show potato and rice proteins can be just as effective at managing your appetite and can help better manage blood glucose levels and reduce spikes in insulin compared to whey protein.

During the study the blood metabolic response of participants was measured after ...

New research has uncovered a novel trick employed by the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus to thwart the immune response, raising hopes that a vaccine that prevents deadly MRSA infections is a little closer on the horizon.

Immunologists from Trinity College Dublin, working with scientists at GSK - one of the world's largest vaccine manufacturers - discovered the new trick of the troublesome Staphylococcus aureus, which is the causative agent of the infamous "superbug" MRSA.

They found that the bacterium interferes with the host immune response by causing toxic effects on white blood cells, which prevents them from engaging in their infection-fighting jobs.

Importantly, the study also showed in a pre-clinical ...

Scientists using computer modelling to study SARS-CoV-2, the virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic, have discovered the virus is most ideally adapted to infect human cells - rather than bat or pangolin cells, again raising questions of its origin.

In a paper published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports, Australian scientists describe how they used high-performance computer modelling of the form of the SARS-CoV-2 virus at the beginning of the pandemic to predict its ability to infect humans and a range of 12 domestic and exotic animals.

Their work aimed to help identify any intermediate animal vector that ...

Although IAT is commonly performed, there is variation in how, why, and where it is done. EULAR aimed to help standardise the way IAT is delivered, and explain to people what they can expect from the treatment. A EULAR taskforce was set up to develop a set of new recommendations to give guidance and advice on best practice for IAT.

The taskforce included doctors, nurses, surgeons, and other health professionals, as well as patients. The taskforce looked at the evidence on IAT. Because there is little published evidence, the taskforce also conducted two surveys ...

Russia is the world's largest forest country. Being home to more than a fifth of forests globally, the country's forests and forestry have enormous potential to contribute to making a global impact in terms of climate mitigation. A new study by IIASA researchers, Russian experts, and other international colleagues have produced new estimates of biomass contained in Russian forests, confirming a substantial increase over the last few decades.

Since the dissolution of the USSR, Russia has been reporting almost no changes in its forests, while data obtained ...

In the animal kingdom, specific growth factors control body axis development. These signalling molecules are produced by a small group of cells at one end of the embryo to be distributed in a graded fashion toward the opposite pole. Through this process, discrete spatial patterns arise that determine the correct formation of the head-foot axis. A research team at the Centre for Organismal Studies (COS) at Heidelberg University recently discovered an enzyme in the freshwater polyp Hydra that critically shapes this process by limiting the activity of certain growth factors.

In particular, the proteins of the so-called Wnt signalling pathway play an important role in the pattern formation of the primary ...

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (06/24/2021) -- A study led by researchers at the University of Minnesota Medical School sheds new light on boys' weapon-carrying behaviors at U.S. high schools. The results indicate that weapon-carrying is not tied to students' race or ethnicity but rather their schools' social climates.

The study was published in the journal Pediatrics and led by Patricia Jewett, PhD, a researcher in the Department of Medicine at the U of M Medical School.

"Narratives of violence in the U.S. have been distorted by racist stereotyping, portraying male individuals of color as more dangerous than white males," Jewett said. "Instead, our study suggests that school climates may be linked to an increase in weapon-carrying at schools."

The ...

Researchers at UCSF have found that extreme caloric restriction diets alter the microbiome in ways that could help with weight loss but might also result in an increased population of Clostridiodes difficile, a pathogenic bacterium that can lead to severe diarrhea and colitis.

Such diets, which allow people only 800 calories per day in liquid form, are an effective approach to weight loss in people with obesity. The unexpected results of this study raise the question of how much the microbiome influences weight loss and which bacteria are significant in that process. The study appears in the June 23, 2021, issue of Nature.

"Our results underscore that the role of calories in weight ...

Using only a pen and paper, a theoretical physicist has proved a decades-old claim that a strong force called Quantum Chromo Dynamics (QCD) leads to light-weight pions, reports a new study published on June 23 in Physical Review Letters.

The strong force is responsible for many things in our Universe, from making the Sun shine, to keeping quarks inside protons. This is important because it makes sure that the protons and neutrons bind to form nuclei of every atom that exists. But there is still a lot of mystery surrounding the strong force. Einstein's relation E=mc2 means a strong force leads to more energy, and more energy means a heavier mass. But subatomic particles called pions ...

Recently, a collaboration of researchers from the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (HFIPS), Universities of Oldenburg (Germany) and Oxford (UK) have been gathering evidence suggesting that a specific light-sensitive protein in the eye named cryptochrome 4 is sensitive to magnetic fields and plays essential roles in magnetic sensing in migratory birds such as European robins. The results have been published in Nature (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03618-9) on June 23 and selected as the cover paper.

For the first time, first author XU Jingjing, a doctoral student in Mouritsen's research group at Oldenburg, with the help of XIE's group, produced cryptochrome 4 in night-migratory ...