New findings on body axis formation

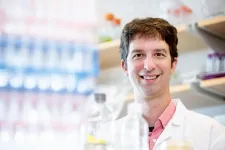

Heidelberg researchers discover an enzyme that prevents the formation of multiple heads and axes in the freshwater polyp Hydra

2021-06-24

(Press-News.org) In the animal kingdom, specific growth factors control body axis development. These signalling molecules are produced by a small group of cells at one end of the embryo to be distributed in a graded fashion toward the opposite pole. Through this process, discrete spatial patterns arise that determine the correct formation of the head-foot axis. A research team at the Centre for Organismal Studies (COS) at Heidelberg University recently discovered an enzyme in the freshwater polyp Hydra that critically shapes this process by limiting the activity of certain growth factors.

In particular, the proteins of the so-called Wnt signalling pathway play an important role in the pattern formation of the primary body axis. Wnt proteins, which arose early during evolution, are considered to be universal developmental factors. "Misregulation of Wnt factors can cause serious malformations during embryonic development and give rise to diseases such as cancer," explains Prof. Dr Özbek, a member of the "Molecular Evolution and Genomics" department led by Prof. Dr Thomas Holstein at the COS.

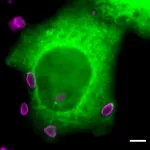

Now, the researchers have discovered an enzyme in the freshwater polyp Hydra that can break down Wnt proteins, thereby deactivating them. Hydra is a basal multicellular organism of the phylum Cnidaria that has long been used as a model organism to study the Spemann-Mangold organizer, an embryonic signalling centre in charge of forming the body's longitudinal axis. The Wnt proteins responsible for this process are continually produced in the mouth region of the adult polyp to maintain the body axis.

The researchers determined that the newly discovered HAS-7 enzyme develops in a ring-shaped zone below Hydra's tentacle wreath. This region separates the head from the body. If HAS-7 production is experimentally interrupted by suppressing the gene expression, a fully formed second head and a second body axis spontaneously develop. According to Prof. Özbek, something similar occurs when Wnt proteins are artificially produced in the animal's entire body.

In cooperation with Prof. Dr Walter Stöcker's group at Mainz University, the Heidelberg researchers were able to show that the HAS-7 enzyme is capable of specifically cleaving the Wnt protein to suppress its activity beyond the head. Without this inhibitory mechanism, the Wnt emanating from the head floods the body, creating a two-headed animal. The HAS-7 enzyme is a member of the astacin family of proteases, which were first identified in crayfish. "Members of the astacin protease family are also found in higher vertebrates. It is therefore likely that we have found a mechanism here that may play a role in humans as well," states Prof. Holstein.

In a follow-up project within the Collaborative Research Centre 1324 "Mechanisms and Functions of Wnt Signaling", the researchers will collaborate with Prof. Dr Irmgard Sinning of the Heidelberg University Biochemistry Center to study the molecular mechanism of Wnt cleavage by astacin. "We hope to be able to find clues on the precise point of attack in the Wnt protein," states Prof. Özbek.

INFORMATION:

In addition to the Heidelberg researchers from the COS and the Institute for Applied Mathematics, scientists from the German Cancer Research Center, Mainz University, the University of Innsbruck (Austria), the Leiden University Medical Center (Netherlands), and the University of Manitoba (Canada) also contributed to the study. Funding was provided by the German Research Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, among others. The results of the research were published in the journal "BMC Biology".

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-24

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (06/24/2021) -- A study led by researchers at the University of Minnesota Medical School sheds new light on boys' weapon-carrying behaviors at U.S. high schools. The results indicate that weapon-carrying is not tied to students' race or ethnicity but rather their schools' social climates.

The study was published in the journal Pediatrics and led by Patricia Jewett, PhD, a researcher in the Department of Medicine at the U of M Medical School.

"Narratives of violence in the U.S. have been distorted by racist stereotyping, portraying male individuals of color as more dangerous than white males," Jewett said. "Instead, our study suggests that school climates may be linked to an increase in weapon-carrying at schools."

The ...

2021-06-24

Researchers at UCSF have found that extreme caloric restriction diets alter the microbiome in ways that could help with weight loss but might also result in an increased population of Clostridiodes difficile, a pathogenic bacterium that can lead to severe diarrhea and colitis.

Such diets, which allow people only 800 calories per day in liquid form, are an effective approach to weight loss in people with obesity. The unexpected results of this study raise the question of how much the microbiome influences weight loss and which bacteria are significant in that process. The study appears in the June 23, 2021, issue of Nature.

"Our results underscore that the role of calories in weight ...

2021-06-24

Using only a pen and paper, a theoretical physicist has proved a decades-old claim that a strong force called Quantum Chromo Dynamics (QCD) leads to light-weight pions, reports a new study published on June 23 in Physical Review Letters.

The strong force is responsible for many things in our Universe, from making the Sun shine, to keeping quarks inside protons. This is important because it makes sure that the protons and neutrons bind to form nuclei of every atom that exists. But there is still a lot of mystery surrounding the strong force. Einstein's relation E=mc2 means a strong force leads to more energy, and more energy means a heavier mass. But subatomic particles called pions ...

2021-06-24

Recently, a collaboration of researchers from the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (HFIPS), Universities of Oldenburg (Germany) and Oxford (UK) have been gathering evidence suggesting that a specific light-sensitive protein in the eye named cryptochrome 4 is sensitive to magnetic fields and plays essential roles in magnetic sensing in migratory birds such as European robins. The results have been published in Nature (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03618-9) on June 23 and selected as the cover paper.

For the first time, first author XU Jingjing, a doctoral student in Mouritsen's research group at Oldenburg, with the help of XIE's group, produced cryptochrome 4 in night-migratory ...

2021-06-24

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - A bout with flu virus can be hard, but when Streptococcus pneumonia enters the mix, it can turn deadly.

Now researchers have found a further reason for the severity of this dual infection by identifying a new virulence mechanism for a surface protein on the pneumonia-causing bacteria S. pneumoniae. This insight comes more than three decades after discovery of that surface protein, called pneumococcal surface protein A, or PspA.

This new mechanism had been missed in the past because it facilitates bacterial adherence only to dead or dying lung epithelial cells, not to living cells. Heretofore, researchers typically used healthy lung ...

2021-06-24

Ultrasound can overcome some of the detrimental effects of ageing and dementia without the need to cross the blood-brain barrier, Queensland Brain Institute researchers have found.

Professor Jürgen Götz led a multidisciplinary team at QBI's Clem Jones Centre for Ageing Dementia Research who showed low-intensity ultrasound effectively restored cognition without opening the barrier in mice models.

The findings provide a potential new avenue for the non-invasive technology and will help clinicians tailor medical treatments that consider an individual's disease progression and cognitive decline.

"Historically, ...

2021-06-24

Are the traditional practices tied to endangered species at risk of being lost? The answer is yes, according to the authors of an ethnographic study published in the University of Guam peer-reviewed journal Pacific Asia Inquiry. But the authors also say a recovery plan can protect both the species as well as the traditional CHamoru practice of consuming them.

Else Demeulenaere, lead author of the study and associate director of the UOG Center for Island Sustainability, presented on their findings during the Marianas Terrestrial Conservation Conference on June 8.

Strong ...

2021-06-24

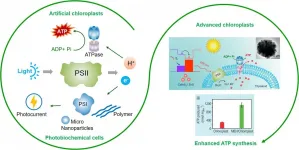

In the recent decade, scientists have paid more attention to studying light harvest for producing novel bionic materials or integrating naturally biological components into synthetic systems. Inspiration is the imitation of natural photosynthesis in green plants, algae, and cyanobacteria to convert light energy into chemical energy. Photosystem II (PSII) is a light-intervened protein complex responsible for the light harvest and water splitting to release O2, protons, and electrons. The development of PSII-based biomimetic assembly in vitro is favorable for the investigation of photocatalysis, biological solar cells, and bionic photosynthesis, further help us reveal more secret of photosynthesis.

The combination of PSII and artificially synthetic structures is successful for ...

2021-06-24

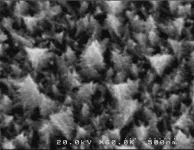

Ishikawa, Japan - Nanostructured metal surface has novel physical and chemical properties, which have sparked scientific interest for heterogeneous catalysis, biosensors, and electrocatalysis. The fabrication process can influence the shapes and sizes of metal nanostructures. Among various fabrication processes, the electrochemical deposition technique is widely used for clean metal nanostructures. Applying the technique, a team of researchers led by Dr. Yuki Nagao, Associate Professor at Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST) and Md. Mahmudul Hasan, a PhD student at JAIST, succeeded to construct Pd-based catalysts having unique morphology.

In this study, the team has successfully synthesized Christmas-tree-shaped palladium nanostructures on the GCE ...

2021-06-24

Toxoplasma gondii, the parasite responsible for toxoplasmosis, is capable of infecting almost all cell types. It is estimated that up to 30% of the world's population is chronically infected, the vast majority asymptomatically. However, infection during pregnancy can result in severe developmental pathology in the unborn child. Like the other members of the large phylum of Apicomplexa, Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasite which, to survive, must absolutely penetrate its host's cells and hijack their functions to its own advantage. Understanding how the parasite manages to enter host cells offers new opportunities to develop more effective prevention and control strategies than those currently available. A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), in collaboration ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New findings on body axis formation

Heidelberg researchers discover an enzyme that prevents the formation of multiple heads and axes in the freshwater polyp Hydra