(Press-News.org) Researchers at UCSF have found that extreme caloric restriction diets alter the microbiome in ways that could help with weight loss but might also result in an increased population of Clostridiodes difficile, a pathogenic bacterium that can lead to severe diarrhea and colitis.

Such diets, which allow people only 800 calories per day in liquid form, are an effective approach to weight loss in people with obesity. The unexpected results of this study raise the question of how much the microbiome influences weight loss and which bacteria are significant in that process. The study appears in the June 23, 2021, issue of Nature.

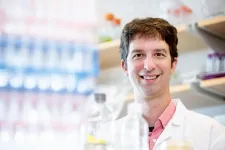

"Our results underscore that the role of calories in weight management is much more complex than simply how much energy a person is taking in," said Peter Turnbaugh, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology and a senior author on the study. "We found that this very-low-calorie diet profoundly altered the gut microbiome, including an overall decrease in gut bacteria."

Turnbaugh and his research team leveraged a clinical trial looking at a very-low-calorie liquid diet. That trial, which resulted in successful weight loss for many of the participants, was led by Joachim Spranger, MD, a professor of endocrinology and metabolic diseases at Charité Universitätsmedizin in Berlin, and co-senior author on the Nature study.

To investigate the microbial connection between this very-low-calorie diet and shedding pounds, Spranger's team collected and sequenced fecal samples from 80 participants - all of whom were post-menopausal women - before and after the trial, which lasted 16 weeks. The team then worked with members of the Turnbaugh lab to analyze the data and to transplant the samples into mice that had been raised in sterile environments.

The researchers allowed these mice to continue eating the same amount of food and found, to their surprise, that the rodents that had received a transplant of the post-diet microbiome lost weight.

"We drove weight loss just by colonizing these mice with a different microbial community," Turnbaugh said.

The next step was to identify bacteria that could be responsible for the weight loss. To do that, Jordan Bisanz, PhD, a former postdoctoral fellow in the Turnbaugh lab and a first author on the study, sequenced the gut microbiomes of the test mice and compared them to those of control mice.

Bisanz discovered a bacterial factor behind changes in weight the team had observed: higher levels of C. difficile.

In the gut, C. difficile is associated with the process of fat metabolism. Initially, fats are digested with the help of bile salts. These bile salts are then broken down by bacteria other than C. difficile, producing what are called secondary bile salts. These bacterial metabolites keep the growth of C. difficile under control. In other words, people who are eating less, particularly less fat, can produce less bile, which in turn leads to fewer secondary bile acids and less of a check on the population of C. difficile.

"Ordinarily we would predict increased inflammation or even colitis following an increase in C. difficile," said Turnbaugh, who is also an investigator at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, Curiously, when he and his team examined the mice, they found only mild inflammation. That lack of inflammation suggests that C. diff could have important effects on metabolism that are distinguishable from the bacterium's ability to drive severe intestinal disease.

At the same time, Turnbaugh notes, it's not at all certain what would happen if someone stayed on the diet for a longer period of time and whether that could result in a full-blown C. difficile infection, which can be life threatening if it gets out of control.

"Let's be clear; we are definitely not promoting C. difficile as a new weight loss strategy," said Turnbaugh. "We've got a lot of biology left to unpack here." The data raise a lot of interesting and unexplored questions about what role C. difficile is playing beyond the severe inflammatory conditions associated with it, he said.

It's important to understand whether diet-induced changes to C. difficile level are harmful in humans, and how the balance between different microbial species in the gut is affected by different dietary choices, Turnbaugh said. Ultimately, that knowledge could allow clinicians to add or remove specific microbes in a patient's gut to help maintain a healthy body weight.

"Multiple lines of research shows that the gut microbiome can either hinder or enhance weight loss," said Turnbaugh. "We want to better understand how common weight loss diets might impact the microbiome and what the downstream consequences are for health and disease."

INFORMATION:

Additional UCSF authors include Peter Spanogiannopoulos, Qi Yan Ang, Su-Yang Liu, Danielle Ingebrigtsen, Steve Miller, Jessie A. Turnbaugh, and Katherine S. Pollard. Pollard is also affiliated with the Gladstone Institutes.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL122593; R21CA227232; P30DK098722; 1R01AR074500; 1R01DK114034) among others. For additional funding and authorship information, please see the study.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

Using only a pen and paper, a theoretical physicist has proved a decades-old claim that a strong force called Quantum Chromo Dynamics (QCD) leads to light-weight pions, reports a new study published on June 23 in Physical Review Letters.

The strong force is responsible for many things in our Universe, from making the Sun shine, to keeping quarks inside protons. This is important because it makes sure that the protons and neutrons bind to form nuclei of every atom that exists. But there is still a lot of mystery surrounding the strong force. Einstein's relation E=mc2 means a strong force leads to more energy, and more energy means a heavier mass. But subatomic particles called pions ...

Recently, a collaboration of researchers from the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (HFIPS), Universities of Oldenburg (Germany) and Oxford (UK) have been gathering evidence suggesting that a specific light-sensitive protein in the eye named cryptochrome 4 is sensitive to magnetic fields and plays essential roles in magnetic sensing in migratory birds such as European robins. The results have been published in Nature (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03618-9) on June 23 and selected as the cover paper.

For the first time, first author XU Jingjing, a doctoral student in Mouritsen's research group at Oldenburg, with the help of XIE's group, produced cryptochrome 4 in night-migratory ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - A bout with flu virus can be hard, but when Streptococcus pneumonia enters the mix, it can turn deadly.

Now researchers have found a further reason for the severity of this dual infection by identifying a new virulence mechanism for a surface protein on the pneumonia-causing bacteria S. pneumoniae. This insight comes more than three decades after discovery of that surface protein, called pneumococcal surface protein A, or PspA.

This new mechanism had been missed in the past because it facilitates bacterial adherence only to dead or dying lung epithelial cells, not to living cells. Heretofore, researchers typically used healthy lung ...

Ultrasound can overcome some of the detrimental effects of ageing and dementia without the need to cross the blood-brain barrier, Queensland Brain Institute researchers have found.

Professor Jürgen Götz led a multidisciplinary team at QBI's Clem Jones Centre for Ageing Dementia Research who showed low-intensity ultrasound effectively restored cognition without opening the barrier in mice models.

The findings provide a potential new avenue for the non-invasive technology and will help clinicians tailor medical treatments that consider an individual's disease progression and cognitive decline.

"Historically, ...

Are the traditional practices tied to endangered species at risk of being lost? The answer is yes, according to the authors of an ethnographic study published in the University of Guam peer-reviewed journal Pacific Asia Inquiry. But the authors also say a recovery plan can protect both the species as well as the traditional CHamoru practice of consuming them.

Else Demeulenaere, lead author of the study and associate director of the UOG Center for Island Sustainability, presented on their findings during the Marianas Terrestrial Conservation Conference on June 8.

Strong ...

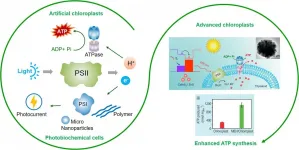

In the recent decade, scientists have paid more attention to studying light harvest for producing novel bionic materials or integrating naturally biological components into synthetic systems. Inspiration is the imitation of natural photosynthesis in green plants, algae, and cyanobacteria to convert light energy into chemical energy. Photosystem II (PSII) is a light-intervened protein complex responsible for the light harvest and water splitting to release O2, protons, and electrons. The development of PSII-based biomimetic assembly in vitro is favorable for the investigation of photocatalysis, biological solar cells, and bionic photosynthesis, further help us reveal more secret of photosynthesis.

The combination of PSII and artificially synthetic structures is successful for ...

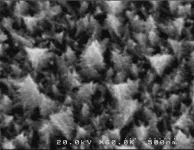

Ishikawa, Japan - Nanostructured metal surface has novel physical and chemical properties, which have sparked scientific interest for heterogeneous catalysis, biosensors, and electrocatalysis. The fabrication process can influence the shapes and sizes of metal nanostructures. Among various fabrication processes, the electrochemical deposition technique is widely used for clean metal nanostructures. Applying the technique, a team of researchers led by Dr. Yuki Nagao, Associate Professor at Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST) and Md. Mahmudul Hasan, a PhD student at JAIST, succeeded to construct Pd-based catalysts having unique morphology.

In this study, the team has successfully synthesized Christmas-tree-shaped palladium nanostructures on the GCE ...

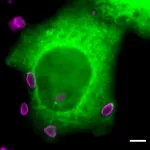

Toxoplasma gondii, the parasite responsible for toxoplasmosis, is capable of infecting almost all cell types. It is estimated that up to 30% of the world's population is chronically infected, the vast majority asymptomatically. However, infection during pregnancy can result in severe developmental pathology in the unborn child. Like the other members of the large phylum of Apicomplexa, Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasite which, to survive, must absolutely penetrate its host's cells and hijack their functions to its own advantage. Understanding how the parasite manages to enter host cells offers new opportunities to develop more effective prevention and control strategies than those currently available. A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), in collaboration ...

An international study led by Helmholtz Zentrum München has revealed the structure of a membrane-remodeling protein that builds and maintains photosynthetic membranes. These fundamental insights lay the groundwork for bioengineering efforts to strengthen plants against environmental stress, helping to sustaining human food supply and fight against climate change.

Plants, algae, and cyanobacteria perform photosynthesis, using the energy of sunlight to produce the oxygen and biochemical energy that power most life on Earth. They also adsorb carbon dioxide (CO?) from the atmosphere, counteracting the accumulation of this greenhouse gas. However, climate change ...

Men - more often than women - need passion to succeed at things. At the same time, boys are diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum four times as often as girls.

Both statistics may be related to dopamine, one of our body's neurotransmitters.

"This is interesting. Research shows a more active dopamine system in most men" than in women, says Hermundur Sigmundsson, a professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU)Department of Psychology.

He is behind a new study that addresses gender differences in key motivating factors for what it takes to become good at something. The study uses men's and women's differing activity in the dopamine system as an explanatory model.

"We looked at gender differences around passion, self-discipline ...