(Press-News.org) Female elephant seal weigh on average 350 kg, and dive continuously to the ocean's mesopelagic zone, about 200 to 1,000 meters deep, to consume their only prey: small fish that weigh less than 10 grams. Now, an international team of researchers, armed with eight years of data, may have answered a decades-long question: How do seals maintain their large size on such small prey?

They published their answer on May 12 in Science Advances.

"It is not easy to get fat," said paper author Taiki Adachi, research fellow with the National Institute of Polar Research and the School of Biology, University of St Andrews. "Elephant seals have to spend almost the whole day -- 20 to 24 hours every day -- deep diving to feed on many small fish and gain body fat stores, which is essential for successful reproduction."

The researchers outfitted 48 female elephant seals with data loggers that tracked everything from location and depth to jaw motion and seal buoyancy, which helps estimate the rate of fat gain. The loggers also used video to capture prey type. They tracked the seals during their two-month post-breeding short migrations in the Northeast Pacific Ocean between 2011 and 2018.

"We focused on this time after breeding because gaining fat energy stores is critical in their annual life cycles to determine whether they will pup again in the next breeding year, ultimately affecting population dynamics," Adachi said.

With more than five million feeding events recorded, the researchers found that, on average, a single seal dove 80 to 100% of the day -- that's about 60 dives a day -- to eat anywhere from 1,000 to 2,000 fish and gain more calories than they burned.

"We suggest that female elephant seals, which are not capable of echolocation or filter-feeding like other large marine mammals, found a unique evolutionary pathway to enhance diving abilities relative to their body mass, allowing them to dive continuously to the mesopelagic depths and maximize feeding opportunities on abundant small fishes," Adachi said. "These results demonstrate the close relationships between body size, prey availability and hunting capacity that shape the foraging guilds within marine animals."

While the elephant seals adapted to a unique foraging niche, according to Adachi, the adaptation may also put the elephant seals at risk as ocean temperatures rise and potentially reduce prey availability.

"We suggest that the narrow behavioral niche of elephant seals severely constrains their plasticity to buffer changes in mesopelagic fish biomass," Adachi said. "The round-the-clock foraging suggest that elephant seals are vulnerable to reduction in prey abundance."

The researchers plan to continue studying elephant seals' foraging activity and monitoring their fat gain rate as an indicator of prey abundance changes.

"The next step is studying elephant seals as an important living sentinel to reveal climate change effect on deep ocean ecosystems," Adachi said.

Co-authors include Akinori Takahashi and Yasuhiko Naito, National Institute of Polar Research; Daniel P. Costa, Patrick W. Robinson, Sarah H. Peterson, Rachel R. Holser and Roxanne S. Beltran, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Santa Cruz; Luis A. Hückstädt, Institute of Marine Sciences, University of California Santa Cruz; Theresa R. Keates, Department of Ocean Sciences, University of California Santa Cruz. Costa and Peterson are also affiliated with the Institute of Marine Sciences, University of California Santa Cruz. Hückstädt is also affiliated with the Department of Biology and Marine Biology, University of North Carolina Wilmington.

The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Office of Naval Research and the E&P Sound and Marine Life Joint Industry Project of the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers funded this work.

INFORMATION:

About National Institute of Polar Research (NIPR)

The NIPR engages in comprehensive research via observation stations in Arctic and Antarctica. As a member of the Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS), the NIPR provides researchers throughout Japan with infrastructure support for Arctic and Antarctic observations, plans and implements Japan's Antarctic observation projects, and conducts Arctic researches of various scientific fields such as the atmosphere, ice sheets, the ecosystem, the upper atmosphere, the aurora and the Earth's magnetic field. In addition to the research projects, the NIPR also organizes the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition and manages samples and data obtained during such expeditions and projects. As a core institution in researches of the polar regions, the NIPR also offers graduate students with a global perspective on originality through its doctoral program. For more information about the NIPR, please visit: https://http://www.nipr.ac.jp/english/

About the Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS)

The Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS) is a parent organization of four national institutes (National Institute of Polar Research, National Institute of Informatics, the Institute of Statistical Mathematics and National Institute of Genetics) and the Joint Support-Center for Data Science Research. It is ROIS's mission to promote integrated, cutting-edge research that goes beyond the barriers of these institutions, in addition to facilitating their research activities, as members of inter-university research institutes.

Genome study reveals East Asian coronavirus epidemic 20,000 years ago

An international study has discovered a coronavirus epidemic broke out in the East Asia region more than 20,000 years ago, with traces of the outbreak evident in the genetic makeup of people from that area.

Professor Kirill Alexandrov from CSIRO-QUT Synthetic Biology Alliance and QUT's Centre for Genomics and Personalised Health, is part of a team of researchers from the University of Arizona, the University of California San Francisco, and the University of Adelaide who have published their findings in the journal Current Biology.

In the past 20 years, there have been three outbreaks of epidemic severe coronaviruses: ...

In the 1950s, researchers made the first unexpected discoveries of dinosaur remains at frigid polar latitudes. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on June 24 have uncovered the first convincing evidence that several species of dinosaur not only lived in what's now Northern Alaska, but they also nested there.

"These represent the northernmost dinosaurs known to have existed," says Patrick Druckenmiller of the University of Alaska Museum of the North. "We didn't just demonstrate the presence of perinatal remains--in the egg or just hatched--of one or two species, rather we documented at ...

Images of dinosaurs as cold-blooded creatures needing tropical temperatures could be a relic of the past.

University of Alaska Fairbanks and Florida State University scientists have found that nearly all types of Arctic dinosaurs, from small bird-like animals to giant tyrannosaurs, reproduced in the region and likely remained there year-round.

Their findings are detailed in a new paper published in the journal Current Biology.

"It wasn't long ago that people were pretty shocked to find out that dinosaurs lived up in the Arctic 70 million years ago," said Pat Druckenmiller, the paper's lead author and director of the ...

The 'anterior cingulate cortex' is key brain region involved in linking behaviours to their outcomes.

When this region was temporarily silenced, monkeys did not change behaviour even when it stopped having the expected outcome.

The finding is a step towards targeted treatment of human disorders involving compulsive behaviour, such as OCD and eating disorders, thought to involve impaired function in this brain region.

Researchers have discovered a specific brain region underlying 'goal-directed behaviour' - that is, when we consciously do something with a particular goal in mind, for example going to the shops to buy food.

The ...

LA JOLLA, CA--New research led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) and the University of Liverpool may explain why many cancer patients do not respond to anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapies--also called checkpoint inhibitors.

The team reports that these patients may have tumors with high numbers of T follicular regulatory (Tfr) cells.

In a healthy person, Tfr cells do the important job of stopping haywire T cells and autoantibodies from attacking the body's own tissues. But in a cancer patient, Tfr cells dramatically dial back the body's ability to kill cancer cells.

Anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapies boost the body's cancer-fighting T cells, but ...

'Precision agriculture' where farmers respond in real time to changes in crop growth using nanotechnology and artificial intelligence (AI) could offer a practical solution to the challenges threatening global food security, a new study reveals.

Climate change, increasing populations, competing demands on land for production of biofuels and declining soil quality mean it is becoming increasingly difficult to feed the world's populations.

The United Nations (UN) estimates that 840 million people will be affected by hunger by 2030, but researchers have developed a roadmap combining smart and nano-enabled agriculture with AI and machine learning capabilities that could help to reduce this ...

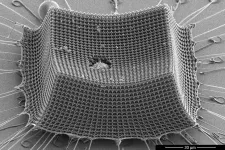

A new study by engineers at MIT, Caltech, and ETH Zürich shows that "nanoarchitected" materials -- materials designed from precisely patterned nanoscale structures -- may be a promising route to lightweight armor, protective coatings, blast shields, and other impact-resistant materials.

The researchers have fabricated an ultralight material made from nanometer-scale carbon struts that give the material toughness and mechanical robustness. The team tested the material's resilience by shooting it with microparticles at supersonic speeds, and found that the material, which is thinner than the width of a human hair, prevented the miniature projectiles from tearing through ...

HAMILTON, ON June 24, 2021 -- The idea of visiting the doctor's office with symptoms of an illness and leaving with a scientifically confirmed diagnosis is much closer to reality because of new technology developed by researchers at McMaster University.

Engineering, biochemistry and medical researchers from across campus have combined their skills to create a hand-held rapid test for bacterial infections that can produce accurate, reliable results in less than an hour, eliminating the need to send samples to a lab.

Their proof-of-concept research, published today in the journal Nature Chemistry, specifically describes the test's ...

In a few years, a new generation of quantum simulators could provide insights that would not be possible using simulations on conventional supercomputers. Quantum simulators are capable of processing a great amount of information since they quantum mechanically superimpose an enormously large number of bit states. For this reason, however, it also proves difficult to read this information out of the quantum simulator. In order to be able to reconstruct the quantum state, a very large number of individual measurements are necessary. The method used to read out the quantum state of a ...

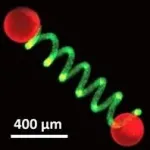

A University of Bristol-led team of international scientists with an interest in protoliving technologies, has today published research which paves the way to building new semi-autonomous devices with potential applications in miniaturized soft robotics, microscale sensing and bioengineering.

Micro-actuators are devices that can convert signals and energy into mechanically driven movement in small-scale structures and are important in a wide range of advanced microscale technologies.

Normally, micro-actuators rely on external changes in bulk properties such as pH and temperature to trigger repeatable mechanical ...