(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio -- Mountaintop glacier ice in the tropics of all four hemispheres covers significantly less area -- in one case as much as 93% less -- than it did just 50 years ago, a new study has found.

The study, published online recently in the journal Global and Planetary Change, found that a glacier near Puncak Jaya, in Papua New Guinea, lost about 93% of its ice over a 38-year period from 1980 to 2018. Between 1986 and 2017 the area covered by glaciers on top of Kilimanjaro in Africa decreased by nearly 71%.

The study is the first to combine NASA satellite imagery with data from ice cores drilled during field expeditions on tropical glaciers around the world. That combination shows that climate change is causing these glaciers, which have long been sources of water for nearby communities, to disappear and indicates that those glaciers have lost ice more quickly in recent years.

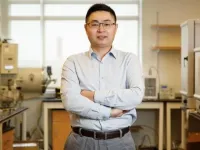

The two datasets allowed the researchers to quantify exactly how much ice has been lost from glaciers in the tropics. Those glaciers are "the canaries in the coal mines," said Lonnie Thompson, lead author of the study, distinguished university professor of Earth Sciences at The Ohio State University and senior research scientist at Ohio State's Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center.

"These are in the most remote parts of our planet--they're not next to big cities, so you don't have a local pollution effect," Thompson said. "These glaciers are sentinels, they're early warning systems for the planet, and they all are saying the same thing."

The study compared changes in the area covered by glaciers in four regions: Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, the Andes in Peru and Bolivia, the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayas of Central and South Asia, and ice fields in Papua, New Guinea, Indonesia. Thompson has led expeditions to all these glaciers and recovered ice cores from each. The cores are long columns of ice that act as timelines of sorts for the regions' climates over centuries to millennia. As snow falls on a glacier each year, it is buried and compressed to form ice layers that trap and preserve the chemistry of snow and whatever is in the atmosphere, including pollutants and biological material such as plants and pollen. Researchers can study those layers and determine what was in the air at the time the ice formed.

One image taken in 2019 of the top of Huascarán, the highest tropical mountain in the world, shows ice retreating upslope and exposing the rock beneath. Analyses performed by researchers at the University of Colorado showed that the area of the glacier ice on top of that mountain decreased by nearly 19% from 1970 to 2003. In 2020, the surface area of the Quelccaya Ice Cap, the second-largest glaciated area in the tropics, had decreased by 46% from 1976, the year Thompson drilled the first ice core from its summit.

Around the time of Thompson's first expedition, NASA launched the first version of its Landsat mission. Landsat is a collection of satellites that photograph Earth's surface and has been in operation in various forms since 1972. It offers the longest continuous space-based record of Earth's land, ice and water.

"We are in this unique position where we have ice core records from these mountaintops, and Landsat has these detailed images of the glaciers, and if we combine those two data sets, we see clearly what is happening," Thompson said.

Glaciers in the tropics respond more quickly to climate change and as they exist in the warmest areas of the world, they can survive only at very high altitudes where the climate is colder. Before Earth's atmosphere warmed, the precipitation there fell as snow. Now, much of it falls as rain that causes the existing ice to melt even faster.

"You're not sustaining the ice at the highest elevations anymore," said co-author Christopher Shuman, associate research professor at the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and associate research scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. "It's this interplay between the warm air lower down melting away the margins of the ice fields while the very highest elevations are still cold enough to get a certain amount of snowfall, but not enough to sustain the ice cap to the dimensions it once was."

That could have profound repercussions for people who live near those glaciers.

The study details the story of one community near the Quelccaya Ice Cap, and the aftermath of a flood caused by massive amounts of ice that fell from the glacier into a nearby glacial lake. The flood destroyed fields that one farming family had spent years cultivating and so frightened the family that they moved four hours away from the community to start a new life in the city.

In Papua New Guinea, the ice has cultural significance for many of the indigenous people who live near the ice fields, as they consider the ice to be the head of their god. Thompson believes the ice fields there will disappear entirely within two or three years.

It is too late for those glaciers, Thompson said, but not too late to attempt to slow the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere, which are causing the planet to warm.

"The science doesn't change the trajectory we're on -- regardless of how clear the science is, we need something to happen to change that trajectory," he said.

INFORMATION:

Other Byrd Center researchers who collaborated on this study include Mary E. Davis, Ellen Mosley-Thompson, and Stacy Porter. Peruvian scientist Gustavo Valdivia Corrales contributed research from the Andes, and Compton J. Tucker of NASA collaborated on satellite imagery. Ice core drilling expeditions were supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Ethnographic fieldwork in Peru was supported in part by Johns Hopkins University.

CONTACTS: Lonnie Thompson, thompson.3@osu.edu

Christopher Shuman, cshuman@umbc.edu

Written by Laura Arenschield, arenschield.2@osu.edu

Cunjiang Yu, Bill D. Cook Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Houston, is reporting the development of a camera with a curvy, adaptable imaging sensor that could improve image quality in endoscopes, night-vision goggles, artificial compound eyes and fish-eye cameras.

"Existing curvy imagers are either flexible but not compatible with tunable focal surfaces, or stretchable but with low pixel density and pixel fill factors," reports Yu in Nature Electronics. "The new imager with kirigami design has a high pixel fill factor, before stretching, of 78% and can retain its optoelectronic performance while being biaxially stretched by 30%."

Modern digital camera systems using conventional rigid, flat imaging sensors require ...

The world's human population is expanding, which means even more agricultural land will be needed to provide food for this growing population. However, choosing which areas to convert is difficult and depends on agricultural and environmental priorities, which can vary widely.

A study led by Princeton University illustrates this challenge by using several different approaches to solve the same puzzle: Given a target amount of food, where should new croplands be put to minimize environmental or biodiversity impacts?

The researchers used the country of Zambia as a case study given that it currently harbors a significant ...

PHILADELPHA--Patients who had their wisdom teeth extracted had improved tasting abilities decades after having the surgery, a new Penn Medicine study published in the journal Chemical Senses found. The findings challenge the notion that removal of wisdom teeth, known as third molars, only has the potential for negative effects on taste, and represent one of the first studies to analyze the long-term effects of extraction on taste.

"Prior studies have only pointed to adverse effects on taste after extraction and it has been generally believed that those effects dissipate over time," said senior author Richard L. Doty, PhD, ...

Annapolis, MD; June 28, 2021--Drones keep getting smaller and smaller, while their potential applications keep getting bigger and bigger. And now unmanned aircraft systems are taking on some of the world's biggest small problems: insect pests.

From crop-munching caterpillars to disease-transmitting mosquitoes, insects that threaten crops, ecosystems, and public health are increasingly being targeted with new pest-management strategies that deploy unmanned aircraft systems (UAS, or drones) for detection and control. And a variety of these applications are featured in a new special collection published this week in ...

A new study has found baby coral reef fishes can outpace all other baby fishes in the ocean.

Lead author Adam Downie is a PhD candidate at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University (Coral CoE at JCU).

Mr Downie said when considering aquatic athletes, young coral reef fishes shine: they are some of the fastest babies, swimming around 15-40 body lengths per second.

As a comparison, herring babies swim up to two body lengths per second, and the fastest human in the water, Olympic gold medalist Michael Phelps, can only swim 1.4 body lengths ...

The year 2020 was a period of economic hardship and significant change in a wide range of sectors for most countries. A team of authors from HSE University has explored how Russia will recover from this crisis and which industries will be affected by the economic recovery. Their study was published in the journal Voprosy ekonomiki.

Last year, the global economy experienced a crisis due to the coronavirus pandemic, with output falling by 3.5% compared to 2019. Russia's decline from the coronavirus measures was more moderate than in many developed countries (industrial ...

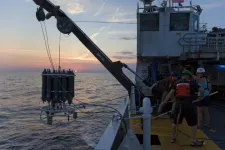

Almost all of the nitrogen that fertilizes life in the open ocean of the Gulf of Mexico is carried into the gulf from shallower coastal areas, researchers from Florida State University found.

The work, published in Nature Communications, is crucial to understanding the food web of that ecosystem, which is a spawning ground for several commercially valuable species of fish, including the Atlantic bluefin tuna, which was a focus of the research.

"The open-ocean Gulf of Mexico is important for a lot of reasons," said Michael Stukel, an associate professor in the Department of Earth, ...

LAWRENCE -- Despite facing cultural and political pushback, the evidence remains clear: Face masks made a difference in Kansas.

"These had a huge effect in counties that had a mask mandate," said Donna Ginther, the Roy A. Roberts Distinguished Professor of Economics and director of the Institute for Policy & Social Research at the University of Kansas. "Our research found that masks reduced cases, hospitalizations and deaths in counties that adopted them by around 60% across the board."

Ginther's article "Association of Mask Mandates and COVID-19 ...

Washington, DC--Location, location, location--when it comes to the placement of wind turbines, the old real estate adage applies, according to new research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Carnegie's Enrico Antonini and Ken Caldeira.

Turbines convert the wind's kinetic energy into electrical energy as they turn. However, the very act of installing turbines affects our ability to harness the wind's power. As a turbine engages with the wind, it affects it. One turbine's extraction of energy from the wind influences the ability of its neighbors to do the same.

"Wind is never going to 'run dry' as an energy resource, but our ability to harvest it isn't infinitely scalable either," Antonini explained. "When wind turbines ...

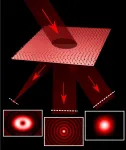

The ability to precisely control the various properties of laser light is critical to much of the technology that we use today, from commercial virtual reality (VR) headsets to microscopic imaging for biomedical research. Many of today's laser systems rely on separate, rotating components to control the wavelength, shape and power of a laser beam, making these devices bulky and difficult to maintain.

Now, researchers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences have developed a single metasurface that can effectively tune the different properties of laser light, ...