(Press-News.org) A team of neuroscientists at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology led by Baher Ibrahim and Dr. Daniel Llano published a study in eLife that furthers our understanding of how the brain perceives everyday sensory inputs.

"There is a traditional idea that the way that we experience the world is sort of like a movie being played on a projector. All the sensory information that is coming in is being played on our cerebral cortex and that's how we see things and hear things," said Llano, a Beckman researcher and associate professor in the Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

However, quite a few studies over the years have challenged this traditional view of how we perceive the world. These studies present a new model: rather than projecting information onto the cortex, the thalamus might be selecting information that is already present in the cortex, based on our learned experiences.

Using a unique mouse brain slice that retains connectivity between three different regions of the brain (midbrain, thalamus, and cortex), Ibrahim and colleagues conducted a series of experiments that involved complicated techniques like electrophysiology, optogenetics, and computer modeling.

Ibrahim discerned that the neurons controlling which signals are relayed to the cortex are cortico-thalamic neurons that act through the thalamic reticular nucleus. These neurons descend from the cortex to the thalamus, making up a population of neurons that is not often talked about, but is nevertheless responsible for controlling what information is relayed to the cortex.

The implications of this research are far-reaching. It is possible to discern from this study that, amongst a veritable sea of sensory inputs, the brain uses these cortico-thalamic neurons to select which sensory inputs to relay up to the cortex via a "non-linear response." This results in humans paying attention to only those sensory inputs that are being relayed to the cortex. Hence, this publication brings to light the neuronal circuitry that is involved in perception-specific sensory information.

"Prior to us doing this particular study, other studies were showing the presence of these non-linear responses in the cortex in other sensory systems, like the visual system. Therefore, I suspect that what we discovered in the auditory system might be a generic mechanism that would be seen across sensory systems with the exception of olfaction," said Llano.

"Learning how to perform all these techniques correctly and efficiently to get reliable data was the most challenging part of this study," added Ibrahim.

Ibrahim, a postdoctoral research associate in Llano's lab, came from a pharmacological scientific background and was not previously trained in performing electrophysiological techniques. This posed unique challenges.

The study ultimately begs the question as to whether everyday sensory perception is a mixture of the internal models of the world that our brain is selecting based on cognitive demand and the input streams flowing from the outside world. This would be a very different way of understanding sensory perception as opposed to what is traditionally taught. Clarity of such concepts is fundamental to understanding situations where these processes of perceptions go awry, namely hallucinations.

The Beckman Institute's recent acquisition of a state-of-the-art multiphoton microscope renders a wide array of possibilities for moving this study forward. This microscope will allow scientists to image the living brain at the cellular level. This will allow Llano and colleagues to study the cerebral cortex of living animals at the cellular level, further allowing them to study hundreds of neurons at a time, and silence specific subpopulations of neurons and see how the responses change.

This study is another step towards understanding the infinitely complex organ that is our brain.

INFORMATION:

Editor's notes:

To reach Dan Llano, call 217-244-0740 or email d-llano@illinois.edu

To reach Baher Ibrahim, call 318-680-6962 or email

bibrahim@illinois.edu

The paper "Corticothalamic gating of population auditory thalamocortical transmission in mouse" is available online at https://elifesciences.org/articles/56645

Many drivers use tollways to get from point A to point B because they are a faster and more convenient option. The fees associated with these roadways are higher during peak traffic hours of the day, such as during the commute to and from work. With this structure, drivers who are not adding to the heavy flow of traffic do not have to pay higher toll prices. However, those who utilize the toll road during more congested hours pay a premium to use the faster, more convenient highways.

Similarly, not everyone uses the same amount of electricity throughout the day. There are peak load hours that put more strain on the grid, and there are users within those times who use more electricity ...

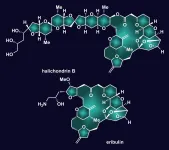

HOUSTON - (June 29, 2021) - The story of halichondrin B, an inspirational molecule obtained from a marine creature, goes back to the molecule's discovery in an ocean sponge in 1986.

Though it has been replicated in the laboratory several times before, new work by Rice University chemists could make halichondrin B and its naturally occurring or designed variations easier to synthesize.

Synthetic chemist K.C. Nicolaou and his lab reported in the Journal of the American Chemical Society their success in simplifying several processes used to make halichondrin B and its variations.

Halichondrin's molecular structure and potent antitumor ...

Dark Energy is widely believed to be the driving force behind the universe's accelerating expansion, and several theories have now been proposed to explain its elusive nature. However, these theories predict that its influence on quantum scales must be vanishingly small, and experiments so far have not been accurate enough to either verify or discredit them. In new research published in EPJ ST, a team led by Hartmut Abele at TU Wien in Austria demonstrate a robust experimental technique for studying one such theory, using ultra-cold neutrons. Named 'Gravity Resonance Spectroscopy' (GRS), their approach could bring researchers ...

Scientists have discovered how plants manage to live alongside each other in places that are dark and shady.

Moderate shade or even the threat of shade - detected by phytochrome photoreceptors - causes plants to elongate to try to outgrow the competition.

But in the deep gloom of a dense forest or a cramped crop canopy where resources and photosynthesis are limited, this strategy doesn't work. In these conditions it would be a waste of energy and detrimental to survival to elongate stems because seedlings would never be able to over-grow larger neighbours.

So how do plants prevent elongated growth under deep shade conditions? The secret lies in their internal clocks, says the research collaboration from the John Innes Centre ...

NEW YORK (June 29, 2021)--In a new paper published in the journal Vaccine: X, public health experts from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, the University of Oslo, and Spark Street Advisors highlight actions to accelerate access to vaccines globally. The paper reviews the vaccine research and development process and proposes areas where reforms could increase access, speed time to market and decrease costs--from R&D to manufacturing and regulation to the management of incentives like patents and public funding.

The COVID-19 ...

A process that uses heat to change the arrangement of molecular rings on a chemical chain creates 3D-printable gels with a variety of functional properties, according to a Dartmouth study.

The researchers describe the new process as "kinetic trapping." Molecular stoppers--or speed bumps--regulate the number of rings going onto a polymer chain and also control ring distributions. When the rings are bunched up, they store kinetic energy that can be released, much like when a compressed spring is released.

Researchers in the Ke Functional Materials Group use heat to change the distribution of rings and then use moisture ...

DURHAM, N.C. - Combining structural biology and computation, a Duke-led team of researchers has identified how multiple mutations on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein independently create variants that are more transmissible and potentially resistant to antibodies.

By acquiring mutations on the spike protein, one such variant gained the ability to leap from humans to minks and back to humans. Other variants -- including Alpha, which first appeared in the United Kingdom, Beta, which appeared in South Africa, and Gamma, first identified in Brazil - independently developed spike mutations that enhanced their ability to spread rapidly in human ...

Aerospace engineering faculty member Melkior Ornik is also a mathematician, a history buff, and a strong believer in integrity when it comes to using hard science in public discussions. So, when a story popped up in his news feed about a pair of researchers who developed a statistical method to analyze datasets and used it to purportedly refute the number of Holocaust victims from a concentration camp in Croatia, it naturally caught his attention.

Ornik is a professor in the Department of Aerospace Engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He proceeded to study the research in depth and used the method to re-analyze the same data from the United ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Mayo Clinic researchers are taking a close look at rare cases of inflammation of the heart muscle, or myocarditis, in young men who developed symptoms shortly after receiving the second dose of the Moderna or Pfizer messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines. Several recent studies suggest that health care professionals should watch for hypersensitivity myocarditis as a rare adverse reaction to being vaccinated for COVID-19. However, researchers stress that this awareness should not diminish overall confidence in vaccination during the current pandemic.

While reports of post-vaccine myocarditis ...

Using real-time deformability cytometry, researchers at the Max-Planck-Zentrum für Physik und Medizin in Erlangen were able to show for the first time: Covid-19 significantly changes the size and stiffness of red and white blood cells - sometimes over months. These results may help to explain why some affected people continue to complain of symptoms long after an infection (long Covid).

Shortness of breath, fatigue and headaches: some patients still struggle with the long-term effects of a severe infection by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus after six months or more. This post Covid-19 syndrome, also called long covid, is still not properly understood. What is clear is that -- during the ...