(Press-News.org) Crystals have fascinated people through the ages. Who hasn't admired the complex patterns of a snowflake at some point, or the perfectly symmetrical surfaces of a rock crystal The magic doesn't stop even if one knows that all this results from a simple interplay of attraction and repulsion between atoms and electrons. A team of researchers led by Atac Imamoglu, professor at the Institute for Quantum Electronics at ETH Zurich, have now produced a very special crystal. Unlike normal crystals, it consists exclusively of electrons. In doing so, they have confirmed a theoretical prediction that was made almost ninety years ago and which has since been regarded as a kind of holy grail of condensed matter physics. Their results were recently published in the scientific journal "Nature".

A decades-old prediction

"What got us excited about this problem is its simplicity", says Imamoglu. Already in 1934 Eugene Wigner, one of the founders of the theory of symmetries in quantum mechanics, showed that electrons in a material could theoretically arrange themselves in regular, crystal-like patterns because of their mutual electrical repulsion. The reasoning behind this is quite simple: if the energy of the electrical repulsion between the electrons is larger than their motional energy, they will arrange themselves in such a way that their total energy is as small as possible.

For several decades, however, this prediction remained purely theoretical, as those "Wigner crystals" can only form under extreme conditions such as low temperatures and a very small number of free electrons in the material. This is in part because electrons are many thousands of times lighter than atoms, which means that their motional energy in a regular arrangement is typically much larger than the electrostatic energy due to the interaction between the electrons.

Electrons in a plane

To overcome those obstacles, Imamoglu and his collaborators chose a wafer-thin layer of the semiconductor material molybdenum diselenide that is just one atom thick and in which, therefore, electrons can only move in a plane. The researchers could vary the number of free electrons by applying a voltage to two transparent graphene electrodes, between which the semiconductor is sandwiched. According to theoretical considerations the electrical properties of molybdenum diselenide should favour the formation of a Wigner crystal - provided that the whole apparatus is cooled down to a few degrees above the absolute zero of minus 273.15 degrees Celsius.

However, just producing a Wigner crystal is not quite enough. "The next problem was to demonstrate that we actually had Wigner crystals in our apparatus", says Tomasz Smolenski, who is the lead author of the publication and works as a postdoc in Imamoglu's laboratory. The separation between the electrons was calculated to be around 20 nanometres, or roughly thirty times smaller than the wavelength of visible light and hence impossible to resolve even with the best microscopes.

Detection through excitons

Using a trick, the physicists managed to make the regular arrangement of the electrons visible despite that small separation in the crystal lattice. To do so, they used light of a particular frequency to excite so-called excitons in the semiconductor layer. Excitons are pairs of electrons and "holes" that result from a missing electron in an energy level of the material. The precise light frequency for the creation of such excitons and the speed at which they move depend both on the properties of the material and on the interaction with other electrons in the material - with a Wigner crystal, for instance.

The periodic arrangement of the electrons in the crystal gives rise to an effect that can sometimes be seen on television. When a bicycle or a car goes faster and faster, above a certain velocity the wheels appear to stand still and then to turn in the opposite direction. This is because the camera takes a snapshot of the wheel every 40 milliseconds. If in that time the regularly spaced spokes of the wheel have moved by exactly the distance between the spokes, the wheel seems not to turn anymore. Similarly, in the presence of a Wigner crystal, moving excitons appear stationary provided they are moving at a certain velocity determined by the separation of the electrons in the crystal lattice.

First direct observation

"A group of theoretical physicists led by Eugene Demler of Harvard University, who is moving to ETH this year, had calculated theoretically how that effect should show up in the observed excitation frequencies of the excitons - and that's exactly what we observed in the lab", Imamoglu says. In contrast to previous experiments based on planar semiconductors, in which Wigner crystals were observed indirectly through current measurements, this is a direct confirmation of the regular arrangement of the electrons in the crystal. In the future, with their new method Imamoglu and his colleagues hope to investigate exactly how Wigner crystals form out of a disordered "liquid" of electrons.

INFORMATION:

Reference

Smolenski, T., Dolgirev, P.E., Kuhlenkamp, C. et al. Signatures of Wigner crystal of electrons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nature 595, 53-57 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03590-4

When researchers at Lund University in Sweden performed advanced analyses of sputum from the airways of severely ill Covid-19 patients, they found high levels of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). It is already a known fact that NETs can contribute to sputum thickness, severe sepsis-like inflammation and thrombosis. After being treated with an already existing drug, the NETs were dissolved and patients improved. The study has now been published in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

Using advanced fluorescence microscopy, the researchers examined sputum in the airways of three severely ...

There might be fewer bonobos left in the wild than we thought. For the last 40 years, scientists have estimated the abundance of endangered bonobos by counting the numbers of sleeping nests left by the apes in forests of the Congo Basin. Now, researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior report that the rate of sleeping nest "decay" has lengthened by 17 days over the last 15 years as a result of declining rainfall in the Congo Basin. The study warns that longer nest decay times have serious implications for ape conservation: failure to account for these ...

DALLAS - June 30, 2021 - A relative decline in wealth during midlife increases the likelihood of a cardiac event or heart disease after age 65 while an increase in wealth between ages 50 and 64 is associated with lower cardiovascular risk, according to a new END ...

The cells that make up our bodies are constantly exposed to a wide variety of mechanical stresses. For example, the heart and lungs have to withstand lifelong expansion and contraction, our skin has to be as resistant to tearing as possible whilst retaining its elasticity, and immune cells are very squashy so that they can move through the body. Special protein structures, known as "intermediate filaments", play an important role in these characteristics. Researchers at Göttingen University have now succeeded for the first time in precisely measuring which physical effects determine the properties of the individual filaments, and which specific features only occur through the interaction ...

Melbourne researchers have found that liquid chalk, commonly used in gyms to improve grip, acts as an antiseptic against highly infectious human viruses, completely killing both SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) and influenza A viruses.

University of Melbourne Professor Jason Mackenzie, a laboratory head at the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) wanted to investigate whether liquid chalk stopped SARS-CoV-2 transmission after conversations with his daughter - an elite rock climber heading to the Tokyo Olympics.

"Both of my daughters were lamenting the closure of gyms at the beginning of the pandemic, particularly my daughter Oceania who was trying to train ...

There are certain rules that even the most extreme objects in the universe must obey. A central law for black holes predicts that the area of their event horizons -- the boundary beyond which nothing can ever escape -- should never shrink. This law is Hawking's area theorem, named after physicist Stephen Hawking, who derived the theorem in 1971.

Fifty years later, physicists at MIT and elsewhere have now confirmed Hawking's area theorem for the first time, using observations of gravitational waves. Their results appear in Physical Review Letters.

In the study, the researchers take a closer look at GW150914, ...

Exercise training can help support management of overweight and obesity in adults, and can contribute to health benefits beyond "scale victories". The supplement published today in Obesity Reviews, based on the work of an expert group convened under the auspices of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), provides scientific evidence on health and wellbeing benefits of exercise training for people living with overweight and obesity. Supplement highlights include a summary of key recommendations; additional developed materials provide infographic tools for health care practitioners (HCPs) and people ...

Economists at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, economists found passers-by often donated more when paying via a digital platforms like apps, QR codes, PayPal and even Bitcoin, compared to the centuries' old payment method of loose coins.

Using data from the online platform The Busking Project, the study analysed individual payments to over three and half thousand active buskers from 121 countries to predict the characteristics of performers who were more likely to receive online donations.

The study found North America and Europe were home to the most active buskers and audiences on the platform, with buskers registered ...

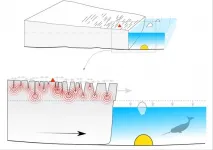

Scientists show that an ocean-bottom seismometer deployed close to the calving front of a glacier in Greenland can detect continuous seismic radiation from a glacier sliding, reminiscent of a slow earthquake.

Basal slip of marine-terminating glaciers controls how fast they discharge ice into the ocean. However, to directly observe such basal motion and determine what controls it is challenging: the calving-front environment is one of the most difficult-to-access environments and seismically noisy -- especially on the glacier surface -- due to heavily crevassed ice and harsh weather conditions.

A team of scientists from Hokkaido University, ...

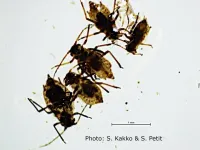

An invasive species of aphid could put some threatened plant species on Kangaroo Island at risk as researchers from the University of South Australia confirm Australia's first sighting of Aphis lugentis on the Island's Dudley Peninsula.

It is another blow for Kangaroo Island's environment, especially following the Black Summer bushfires that decimated more than half the island and 96 per cent of Flinders Chase National Park.

Collected by wildlife ecologist Associate Professor Topa Petit and identified by colleagues from the WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, the black aphids were found feeding on seedlings of Senecio odoratus, a native species of daisy, commonly known as the scented groundsel.

Of ...