(Press-News.org) Current rates of plastic emissions globally may trigger effects that we will not be able to reverse, argues a new study by researchers from Sweden, Norway and Germany published on July 2nd in Science. According to the authors, plastic pollution is a global threat, and actions to drastically reduce emissions of plastic to the environment are "the rational policy response".

Plastic is found everywhere on the planet: from deserts and mountaintops to deep oceans and Arctic snow. As of 2016, estimates of global emissions of plastic to the world's lakes, rivers and oceans ranged from 9 to 23 million metric tons per year, with a similar amount emitted onto land yearly. These estimates are expected to almost double by 2025 if business-as-usual scenarios apply.

"Plastic is deeply engrained in our society, and it leaks out into the environment everywhere, even in countries with good waste-handling infrastructure," says Matthew MacLeod, Professor at Stockholm University and lead author of the study. He says that emissions are trending upward even though awareness about plastic pollution among scientists and the public has increased significantly in recent years.

That discrepancy is not surprising to Mine Tekman, a PhD candidate at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany and co-author of the study, because plastic pollution is not just an environmental issue but also a "political and economic" one. She believes that the solutions currently on offer, such as recycling and cleanup technologies, are not sufficient, and that we must tackle the problem at its root.

"The world promotes technological solutions for recycling and to remove plastic from the environment. As consumers, we believe that when we properly separate our plastic trash, all of it will magically be recycled. Technologically, recycling of plastic has many limitations, and countries that have good infrastructures have been exporting their plastic waste to countries with worse facilities. Reducing emissions requires drastic actions, like capping the production of virgin plastic to increase the value of recycled plastic, and banning export of plastic waste unless it is to a country with better recycling" says Tekman.

A poorly reversible pollutant of remote areas of the environment

Plastic accumulates in the environment when amounts emitted exceed those that are removed by cleanup initiatives and natural environmental processes, which occurs by a multi-step process known as weathering.

"Weathering of plastic happens because of many different processes, and we have come a long way in understanding them. But weathering is constantly changing the properties of plastic pollution, which opens new doors to more questions," says Hans Peter Arp, researcher at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI) and Professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) who has also co-authored the study. "Degradation is very slow and not effective in stopping accumulation, so exposure to weathered plastic will only increase," says Arp. Plastic is therefore a "poorly reversible pollutant", both because of its continuous emissions and environmental persistence.

Remote environments are particularly under threat as co-author Annika Jahnke, researcher at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) and Professor at the RWTH Aachen University explains:

"In remote environments, plastic debris cannot be removed by cleanups, and weathering of large plastic items will inevitably result in the generation of large numbers of micro- and nanoplastic particles as well as leaching of chemicals that were intentionally added to the plastic and other chemicals that break off the plastic polymer backbone. So, plastic in the environment is a constantly moving target of increasing complexity and mobility. Where it accumulates and what effects it may cause are challenging or maybe even impossible to predict."

A potential tipping point of irreversible environmental damage

On top of the environmental damage that plastic pollution can cause on its own by entanglement of animals and toxic effects, it could also act in conjunction with other environmental stressors in remote areas to trigger wide-ranging or even global effects. The new study lays out a number of hypothetical examples of possible effects, including exacerbation of climate change because of disruption of the global carbon pump, and biodiversity loss in the ocean where plastic pollution acts as additional stressor to overfishing, ongoing habitat loss caused by changes in water temperatures, nutrient supply and chemical exposure.

Taken all together, the authors view the threat that plastic being emitted today may trigger global-scale, poorly reversible impacts in the future as "compelling motivation" for tailored actions to strongly reduce emissions.

"Right now, we are loading up the environment with increasing amounts of poorly reversible plastic pollution. So far, we don't see widespread evidence of bad consequences, but if weathering plastic triggers a really bad effect we are not likely to be able to reverse it," cautions MacLeod. "The cost of ignoring the accumulation of persistent plastic pollution in the environment could be enormous. The rational thing to do is to act as quickly as we can to reduce emissions of plastic to the environment."

INFORMATION:

Original publication:

Matthew MacLeod, Hans Peter H. Arp, Mine B. Tekman, Annika Jahnke: The global threat from plastic pollution, Science (2021). DOI: 10.1126/science.abg5433

Participating Institutions and Contacts:

Stockholm University: Matthew MacLeod (Matthew.MacLeod@aces.su.se)

Norwegian Geotechnical Institute: Hans Peter Arp (Hans.Peter.Arp@ngi.no)

Alfred Wegener Institute: Mine Tekman (mine.banu.tekman@awi.de)

Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research: Annika Jahnke (annika.jahnke@ufz.de)

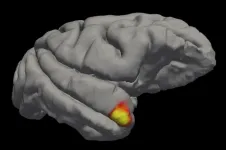

Scientists have long searched in vain for a class of brain cells that could explain the visceral flash of recognition that we feel when we see a very familiar face, like that of our grandmothers. But the proposed "grandmother neuron"--a single cell at the crossroads of sensory perception and memory, capable of prioritizing an important face over the rabble--remained elusive.

Now, new research reveals a class of neurons in the brain's temporal pole region that links face perception to long-term memory. It's not quite the apocryphal grandmother neuron--rather than a single ...

The COVID-19 catastrophe in India has resulted in more than 30 million people infected with the virus and nearly 400,000 deaths, though experts are concerned that the figures most likely are much higher. Meanwhile, another public health crisis has emerged along with COVID-19: the widespread misuse of antibiotics.

During India's first surge of COVID-19, antibiotic sales soared, suggesting the drugs were used to treat mild and moderate cases of COVID-19, according to research led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Such use is considered inappropriate because antibiotics are only effective against bacterial infections, not viral infections such as COVID-19, and overuse increases the risk ...

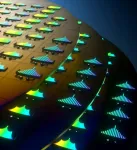

Fifteen years ago, UC Santa Barbara electrical and materials professor John Bowers pioneered a method for integrating a laser onto a silicon wafer. The technology has since been widely deployed in combination with other silicon photonics devices to replace the copper-wire interconnects that formerly linked servers at data centers, dramatically increasing energy efficiency -- an important endeavor at a time when data traffic is growing by roughly 25% per year.

For several years, the Bowers group has collaborated with the group of Tobias J. Kippenberg at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL), within the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Direct On-Chip Digital Optical ...

Optical frequency combs consist of light frequencies made of equidistant laser lines. They have already revolutionized the fields of frequency metrology, timing and spectroscopy. The discovery of ''soliton microcombs'' by Professor Tobias Kippenberg's lab at EPFL in the past decade has enabled frequency combs to be generated on chip. In this scheme, a single-frequency laser is converted into ultra-short pulses called dissipative Kerr solitons.

Soliton microcombs are chip-scale frequency combs that are compact, consume low power, and exhibit broad bandwidth. Combined with large spacing of comb "teeth", microcombs are uniquely ...

Conversations between seriously ill people, their families and palliative care specialists lead to better quality-of-life. Understanding what happens during these conversations - and particularly how they vary by cultural, clinical, and situational contexts - is essential to guide healthcare communication improvement efforts. To gain true understanding, new methods to study conversations in large, inclusive, and multi-site epidemiological studies are required. A new computer model offers an automated and valid tool for such large-scale scientific analyses.

Research results on this model were published today in PLOS ONE.

Developed by a team of computer scientists, clinicians and engineers at the University of Vermont, the approach - called CODYM ...

A study by Stanford University School of Medicine investigators hints that people with COVID-19 may experience milder symptoms if certain cells of their immune systems "remember" previous encounters with seasonal coronaviruses -- the ones that cause about a quarter of the common colds kids get.

These immune cells are better equipped to mobilize quickly against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19, if they've already met its gentler cousins, the scientists concluded.

The findings may help explain why some people, particularly children, seem much more resilient than others to infection by SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. They also might make it possible ...

Scientists have developed a new technology to detect a wider variety of T cells that recognize coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2. The technology revealed that killer T cells capable of recognizing epitopes conserved across all coronaviruses are much more abundant in COVID-19 patients with mild disease versus those with more severe illness, suggesting a protective role for these broad-affinity T cells. The ability to distinguish T cells based on their affinities to SARS-CoV-2 could help scientists elucidate the disparity in COVID-19 outcomes and determine which COVID-19 patients will or will not exhibit a successful immune response ...

In a new Editorial, Peter Heeger, Christian Larsen, and Dorry Segev discuss recent evidence - including a recent Science Immunology study by Hector Rincon-Arevalo and colleagues - that points to a diminished immune response to COVID-19 vaccines among organ transplant recipients and others on immunosuppressive drug regimens. The authors note that this presents challenges at both the individual and population levels, since current vaccine protocols may not provide adequate protection to immunosuppressed patients - who could, in turn, become reservoirs for new and dangerous variants of the virus. As such, Heeger, Larsen, and Segev argue that developing vaccination strategies for transplant recipients should be a high priority in the next wave of research focused on fighting COVID-19. ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Research by investigators at Mayo Clinic Cancer Center suggests that physicians should screen patients with lung cancer for MET amplification/overexpression before determining a treatment strategy. Their findings are published Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"In our research we found several lung cancer cases that were not responsive to standard chemotherapy," says Zhenkun Lou, Ph.D., a cancer researcher at Mayo Clinic. "Because these lung cancers were positive for PD-L1, a protein that allows some cells ...

A key factor in America's prodigious agricultural output turns out to be something farmers can do little to control: clean air. A new Stanford-led study estimates pollution reductions between 1999 and 2019 contributed to about 20 percent of the increase in corn and soybean yield gains during that period - an amount worth about $5 billion per year.

The analysis, published this week in Environmental Research Letters, reveals that four key air pollutants are particularly damaging to crops, and accounted for an average loss of about 5 percent of corn and soybean production over the study period. The findings could help inform technology and policy changes to benefit American agriculture, and underscore the ...