(Press-News.org) A study published the week of July 5 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences led by Michael Moore at Washington University in St. Louis finds that dragonfly males have consistently evolved less breeding coloration in regions with hotter climates.

"Our study shows that the wing pigmentation of dragonfly males evolves so consistently in response to the climate that it's among the most predictable evolutionary responses ever observed for a mating-related trait," said Moore, who is a postdoctoral fellow with the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University.

"This work reveals that mating-related traits can be just as important to how organisms adapt to their climates as survival-related traits," he said.

Many dragonflies have patches of dark black pigmentation on their wings that they use to court potential mates and intimidate rivals.

"Beyond its function in reproduction, having a lot of dark pigmentation on the wings can heat dragonflies up by as much as 2 degrees Celsius, quite a big shift!" Moore said, noting that would roughly equal a 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit change. "While this pigmentation can help dragonflies find mates, extra heating could also cause them to overheat in places that are already hot."

The researchers were interested in whether this additional heating might force dragonflies to evolve different amounts of wing pigmentation in different climates.

For this study, the scientists created a database of 319 dragonfly species using field guides and citizen-scientist observations. They examined the wing ornamentation shown in photographs submitted to iNaturalist and gathered information about climate variables in the locations where the dragonflies were observed. The researchers also directly measured the amount of wing pigmentation on individual dragonflies from almost 3,000 iNaturalist observations in a focused group of 10 selected species. For dragonflies in each of these 10 species, the scientists evaluated how populations differed in the warm and cool parts of their geographic ranges.

Whether they compared species with hotter versus cooler geographic ranges, or compared populations of the same species that live in warmer areas versus cooler areas, the researchers saw the same thing: male dragonflies nearly always responded to warmer temperatures by evolving less wing pigmentation.

Sorting the observations another way, the researchers determined that male dragonflies spotted in warmer years tended to have less wing pigmentation than male dragonflies of the same species in cooler years (the database included observations recorded during the time period from 2005-19).

"Given that our planet is expected to continue warming, our results suggest that dragonfly males may eventually need to adapt to global climate change by evolving less wing coloration," Moore said.

The study includes projections, based on climate warming scenarios, that indicate it will be beneficial for male wing pigmentation to shrink further as the Earth warms over the next 50 years.

But the changes are not happening the same way for both sexes.

"Unlike the males, dragonfly females are not showing any major shifts in how their wing coloration is changing with the current climate. We don't yet know why males and females are so different, but this does show that we shouldn't assume that the sexes will adapt to climate change in the same way," Moore said.

Dragonflies have different amounts of pigment on their wings that help males and females of the same species identify each other. One of the interesting implications of this research is that if the male wing pigmentation evolves in response to rapid changes in climate and the female pigmentation evolves in response to something else, females may no longer recognize males of their own species.

This could cause them to mate with males of the wrong species.

"Rapid changes in mating-related traits might hinder a species' ability to identify the correct mate," Moore said. "Even though our research suggests these changes in pigmentation seem likely to happen as the world warms, the consequences are something we still really don't know all that much about yet."

INFORMATION:

This work was completed in collaboration with: Kim Medley, director of Washington University's environmental field station, Tyson Research Center; Kasey Fowler-Finn, an associate professor of biology at Saint Louis University; and Washington University undergraduates Kaitlyn Hersch, Chanont Sricharoen, Sarah Lee, Caitlin Reice, Paul Rice and Sophie Kronick.

Scientists recently made news by using fossil shark scales to reconstruct shark communities from millions of years ago. At the same time, an international team of researchers led by UC Santa Barbara ecologist Erin Dillon applied the technique to the more recent past.

Human activities have caused shark populations to plummet worldwide since records began in the mid-20th century. However, the scientists were concerned that these baseline data may, themselves, reflect shark communities that had already experienced significant declines. Dillon compared the abundance and variety of shark scales from a Panamanian coral reef 7,000 years ago to those in reef sediments ...

A vast seabird colony on Ascension Island creates a "halo" in which fewer fish live, new research shows.

Ascension, a UK Overseas Territory, is home to tens of thousands of seabirds - of various species - whose prey incudes flying fish.

The new study, by the University of Exeter and the Ascension Island Government, finds reduced flying fish numbers up to 150km (more than 90 miles) from the island - which could only be explained by the foraging of seabirds.

The findings - which provide rare evidence for a long-standing theory first proposed at Ascension - show how food-limited seabird populations naturally are, and why they are often so sensitive to competition with human fishers. ...

Nanomaterials found in consumer and health-care products can pass from the bloodstream to the brain side of a blood-brain barrier model with varying ease depending on their shape - creating potential neurological impacts that could be both positive and negative, a new study reveals.

Scientists found that metal-based nanomaterials such as silver and zinc oxide can cross an in vitro model of the 'blood brain barrier' (BBB) as both particles and dissolved ions - adversely affecting the health of astrocyte cells, which control neurological responses.

But the researchers also believe that their discovery will help to design safer nanomaterials and could open ...

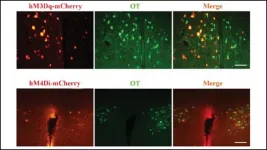

Like female voles, connections between oxytocin neurons in the hypothalamus and dopamine neurons in reward areas drive parental behaviors in male voles, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

Motherhood receives most of the attention in the research world, yet in 5% of mammals -- including humans -- fathers provide care, too. The "love hormone" oxytocin plays a role in paternal care, but the exact neural pathways underlying the behavior were not known.

He et al. measured the neural activity of vole fathers while they interacted with their offspring. Oxytocin neurons connecting the hypothalamus to a reward area fired when the fathers cared for their offspring. ...

The psychedelic drug psilocybin, a naturally occurring compound found in some mushrooms, has been studied as a potential treatment for depression for years. But exactly how it works in the brain and how long beneficial results might last is still unclear.

In a new study, Yale researchers show that a single dose of psilocybin given to mice prompted an immediate and long-lasting increase in connections between neurons. The findings are published July 5 in the journal Neuron.

"We not only saw a 10% increase in the number of neuronal connections, but also they were on average about 10% larger, so the connections were stronger as well," said Yale's Alex Kwan, associate professor of psychiatry and of neuroscience and senior author of the paper.

Previous ...

A new collaborative research led by researchers from the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Ritsumeikan University, and Kyoto University found that although unlimited irrigation could increase global BECCS potential (via the increase of bioenergy production) by 60-71% by the end of this century, sustainably constrained irrigation would increase it by only 5-6%. The study has been published in Nature Sustainability on July 5.

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is a process of extracting bioenergy from biomass, ...

"The number of black holes is roughly three times larger than expected from the number of stars in the cluster, and it means that more than 20% of the total cluster mass is made up of black holes. They each have a mass of about 20 times the mass of the Sun, and they formed in supernova explosions at the end of the lives of massive stars, when the cluster was still very young" says Prof Mark Gieles, from the Institute of Cosmos Sciences of the University of Barcelona (ICCUB) and lead author of the paper.

Tidal streams are streams of stars that were ejected from disrupting ...

Land plants - plants that live primarily in terrestrial habitats and form vegetation on earth - are anchored to the ground through their roots, and their performance depends on both the belowground soil conditions and the aboveground climate. Plants utilize sunlight to grow through the process of photosynthesis where light energy is converted to chemical energy in chloroplasts, the powerhouses of plant cells. Therefore, the amount and quality of light perceived by chloroplasts through light absorbing pigments, such as chlorophyll, is a defining factor in plant growth and health. ...

MADISON, Wis. -- About 100 additional wolves died over the winter in Wisconsin as a result of the delisting of grey wolves under the Endangered Species Act, alongside the 218 wolves killed by licensed hunters during Wisconsin's first public wolf hunt, according to new research.

The combined loss of 313 to 323 wolves represents a decline in the state's wolf population of between 27% and 33% between April 2020 and April 2021. Researchers estimate that a majority of these additional, uncounted deaths are due to something called cryptic poaching, where poachers hide evidence of illegal killings.

The findings are the first estimate of Wisconsin's wolf population since the public hunt in February, which ended early after hunters ...

The theory that modern society is too clean, leading to defective immune systems in children, should be swept under the carpet, according to a new study by researchers at UCL and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

In medicine, the 'hygiene hypothesis' states that early childhood exposure to particular microorganisms protects against allergic diseases by contributing to the development of the immune system.

However, there is a pervading view (public narrative) that Western 21st century society is too hygienic, which means toddlers and children are likely to be less exposed to germs in early life and so become less resistant to allergies.

In this paper, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, researchers point to four significant reasons which, ...