(Press-News.org) "Equal pay for equal work," a motto touted by many people, turns out to be relevant to the plant world as well. According to new research by Stanford University ecologists, plants allocate resources to their microbial partners in proportion to how much they benefit from that partnership.

"The vast majority of plants rely on microbes to provide them with the nutrients they need to grow and reproduce," explained Brian Steidinger, a former postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Stanford ecologist, Kabir Peay. "The problem is that these microbes differ in how well they do the job. We wanted to see how the plants reward their microbial employees."

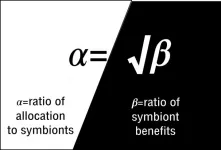

In a new study, published July 6 in the journal American Naturalist, the researchers investigated this question by analyzing data from several studies that detail how different plants "pay" their symbionts with carbon relative to the "work" those symbionts perform for the plants - in the form of supplying nutrients, like phosphorus and nitrogen. What they found was that plants don't quite achieve "equal pay" because they tend not to penalize low-performing microbes as much as would be expected in a truly equal system. The researchers were able to come up with a simple mathematical equation to represent most of the plant-microbe exchanges they observed.

"It's a square root relationship," said Peay, who is an associate professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences. "Meaning, if microbe B does one-quarter as much work as microbe A, it still gets 50 percent as many resources - the square root of one-quarter."

When the researchers tested their equation against 13 measurements of plant resource exchange with microbe partners, they were able to explain around 66 percent of the variability in the ratio of plant payments to two different microbes.

"The biggest surprise was the simplicity of the model," said Steidinger. "You don't get a lot of short equations in ecology. Or anywhere else."

The fruit of frustration

When asked about the motivation for developing this equation, Steidinger summed it up with one word: frustration.

"There is a lot of really interesting literature in a field called 'biological market theory' that deals with how plants should preferentially allocate resources. But for the folks who actually run experiments, it is difficult to translate these models into clean predictions," said Steidinger. "We wanted to make that clean prediction."

An informal survey of the Peay lab members encouraged the researchers to start with the assumption of equal pay because most people agreed it was reasonable to guess that plants treat all microbes the same. To reach their final equation, Steidinger and Peay then factored in the diminishing returns seen in the fertilizer models and assessed them through the lens of biological market theory literature - which uses human markets as a mathematical analogy for exchanges of services in the natural world.

"It turns out if the plant is flush with resources - in this case, the sugars it feeds to its microbes - and if the nutrients are valuable enough, the plant pays its microbes according to a square-root law," said Peay.

The square-root model is a strong start to addressing Steidinger's original frustration but it is not quite at the level of realism he wants to eventually achieve.

"For instance, our model allows a useless microbe to be fired without the plant losing resources," said Steidinger. "But, just as in the human world, it takes an investment to hire a microbe and that initial investment is a gamble that microbial layabouts can consume at their leisure."

Weber's Law

In an attempt to explain why plants follow the square-root model, the researchers turned to a law in psychology. Weber's Law addresses how humans perceive differences in stimuli, such as noise, light or the size of different objects. It explains that, the stronger the stimuli, the worse we are at identifying when it changes. This law has been shown to hold for many non-human animals as well - describing, for example, how birds and bats forage for food and how fish school. Now the researchers suggest it's a good analogy for their plant payment scheme too.

"Our model says that plant should go easy on low-performing microbes, seemingly overpaying the 25-percent-as-good microbe with 50 percent as much resources," said Peay. "Well, it's long been known that humans and non-human animals sense differences in quantity in a way that might bias them towards similar leniency."

In other words, the researchers suggest that, like a human trying to detect the volumes of specific noises in a loud room, a plant making optimal payment decisions may be relatively insensitive to differences in the quality of its microbial employees. And the researchers argue that this insensitivity may be for the best, as it encourages plants to maintain a certain level of microbial diversity, which can help give the plant options for dealing with environmental changes it encounters throughout its lifetime.

"I think what we're seeing is plants behave like animals not because they have the same perceptional limitations - and certainly not because they think like animals - but because we face similar challenges in making the best choices when there are diminishing returns on investment," says Steidinger.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Biological & Environmental Research, Early Career Research Program; the National Science Foundation Division of Environmental Biology; and an Alexander von Humboldt Postdoctoral Research Fellowship.

Very recently, researchers led by Markus Aspelmeyer at the University of Vienna and Lukas Novotny at ETH Zurich cooled a glass nanoparticle into the quantum regime for the first time. To do this, the particle is deprived of its kinetic energy with the help of lasers. What remains are movements, so-called quantum fluctuations, which no longer follow the laws of classical physics but those of quantum physics. The glass sphere with which this has been achieved is significantly smaller than a grain of sand, but still consists of several hundred million atoms. In contrast to ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- You dash into a convenience store for a quick snack, spot an apple and reach for a candy bar instead. Poor self-control may not be the only factor behind your choice, new research suggests. That's because our brains process taste information first, before factoring in health information, according to new research from Duke University.

"We spend billions of dollars every year on diet products, yet most people fail when they attempt to diet," said study co-author Scott Huettel, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke. "Taste seems to have an advantage that sets us up for failure."

"For many individuals, health information enters the decision process ...

Injecting sulphur into the stratosphere to reduce solar radiation and stop the Greenland ice cap from melting. An interesting scenario, but not without risks. Climatologists from the University of Liège have looked into the matter and have tested one of the scenarios put forward using the MAR climate model developed at the University of Liège. The results are mixed and have been published in the journal The Cryosphere.

The Greenland ice sheet will lose mass at an accelerated rate throughout the 21st century, with a direct link between anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and the extent of Greenland's mass loss. To combat this phenomenon, and therefore global warming, it is essential to reduce ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - An interdisciplinary team of Cornell and Harvard University researchers developed a machine learning tool to parse quantum matter and make crucial distinctions in the data, an approach that will help scientists unravel the most confounding phenomena in the subatomic realm.

The Cornell-led project's paper, "Correlator Convolutional Neural Networks as an Interpretable Architecture for Image-like Quantum Matter Data," published June 23 in Nature Communications. The lead author is doctoral student Cole Miles.

The Cornell team was led by Eun-Ah Kim, professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences, who partnered with Kilian Weinberger, associate professor of computing and information science in the Cornell Ann S. ...

When you insist you're not racist, you may unwittingly be sending the opposite message.

That's the conclusion of a new study* by three Berkeley Haas researchers who conducted experiments with white participants claiming to hold egalitarian views. After asking them to write statements explaining why they weren't prejudiced against Black people, they found that other white people could nevertheless gauge the writers' underlying prejudice.

"Americans almost universally espouse egalitarianism and wish to see themselves as non-biased, yet racial prejudice persists," says Berkeley ...

A genetic map of an aggressive childhood brain tumour called medulloblastoma has helped researchers identify a new generation anti-cancer drug that can be repurposed as an effective treatment for the disease.

This international collaboration, led by researchers from The University of Queensland's (UQ) Diamantina Institute and WEHI in Melbourne, could give parents hope in the fight against the most common and fatal brain cancer in children.

UQ lead researcher Dr Laura Genovesi said the team had mapped the genetics of these aggressive brain tumours for five years to find new pathways that existing drugs could potentially target.

"These are drugs already approved for other diseases or cancers but have never been tested in paediatric brain tumours," Dr Genovesi ...

ST. LOUIS -- In the United States, low-income and minority students are completing college at low rates compared to higher-income and majority peers -- a detriment to reducing economic inequality. Double-dose algebra could be a solution, according to a new study published in roceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

The paper, "Effects of Double-Dose Algebra on College Persistence and Degree Attainment," is the culmination of a series of studies that followed two cohorts of ninth-grade students over a period of 12 years in the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) where double-dose algebra ...

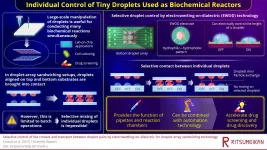

Miniaturization is rapidly reshaping the field of biochemistry, with emerging technologies such as microfluidics and "lab-on-a-chip" devices taking the world by storm. Chemical reactions that were normally conducted in flasks and tubes can now be carried out within tiny water droplets not larger than a few millionths of a liter. Particularly, in droplet-array sandwiching techniques, such tiny droplets are orderly laid out on two parallel flat surfaces opposite to each other. By bringing the top surface close enough to the bottom one, each top droplet makes contact with the opposite bottom droplet, exchanging chemicals and transferring particles or even cells. In quite a literal way, these droplets can act as small reaction ...

BUFFALO, N.Y -- Children who eat slower are less likely to be extroverted and impulsive, according to a new study co-led by the University at Buffalo and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

The research, which sought to uncover the relationship between temperament and eating behaviors in early childhood, also found that kids who were highly responsive to external food cues (the urge to eat when food is seen, smelled or tasted) were more likely to experience frustration and discomfort and have difficulties self-soothing.

These findings are critical because faster eating and greater responsiveness to food cues have been linked to obesity risk in children, ...

A new study examining why young South Asian heart attack patients have more adverse outcomes found this patient population was often obese, used tobacco products, and had a family history of heart disease or risk factors that could have been prevented, monitored for or treated before heart attacks happen. The study will be presented at the ACC Asia 2021 Together with SCS 32nd Annual Scientific Meeting Virtual being held July 9-11, 2021.

"South Asians tend to have multiple co-morbidities including diabetes and obesity at younger ages which is different from the white population," said Salik ur Rehman Iqbal, ...