INFORMATION:

Wastewater did not significantly alter seismic stress direction in southern Kansas

2021-07-07

(Press-News.org) Although wastewater disposal has been the primary driving force behind increased earthquake activity in southern Kansas since 2013, a new study concludes that the disposal has not significantly changed the orientation of stress in the Earth's crust in the region.

Activities like wastewater disposal can alter pore pressure, shape and size within rock layers, in ways that cause nearby faults to fail during an earthquake. These effects are thought to be behind most recent induced earthquakes in the central and eastern United States.

It is possible, however, that human activity could also lead to earthquakes by altering the orientation of stresses that act on faults in the region, said U.S. Geological Survey seismologist Robert Skoumal, who co-authored the study in Seismological Research Letters with USGS seismologist Elizabeth Cochran.

"Since we do not see evidence for a significant stress rotation [in the region], we think most of the earthquakes in southern Kansas are due to changes in pore pressures or porelastic effects rather than due to stress rotations," Skoumal said.

One way that researchers can learn more about the orientation of the stress field in rock layers where fluid fills fractures in the rock is through a seismic wave effect called shear wave splitting. Some of the shear waves traveling through the rock move parallel to open fractures and are therefore faster, while others move perpendicular to the fractures and have a lower velocity. Estimating the direction of the fast waves can help determine the orientation of the stress field.

A previous shear wave splitting study in southern Kansas estimated a 90-degree rotation in the fast direction beginning in 2015, which the study authors attributed to elevated pore fluid pressures from wastewater disposal. However, the rotation coincided with a change in the stations used to observe the shear waves.

Skoumal and Cochran decided to take another look at stress changes in southern Kansas as part of a larger effort to characterize stress in rock reservoirs without drilling expensive boreholes. When they analyzed shear wave splitting using high-quality data collected from a stable local seismic network, they found that the regional stress orientation remained relatively constant between 2014 and 2017.

The geological conditions of a wastewater reservoir might affect whether injection can alter stress orientation, Skoumal noted. Most of the wastewater injected in southern Kansas went into rock layers called the Arbuckle Group, "which is underpressurized--fluid can be 'poured in' without the need of a pump," Skoumal said, noting that pore pressures can diffuse rapidly in the highly permeable rock.

There are no reports of significant stress rotations due to wastewater disposal, the authors note, suggesting that it may either not be a common occurrence, the stress rotations are smaller than can be detected with current methods, or that the phenomenon hasn't been studied enough. Until recently, seismic instrumentation has been sparse in many places that have experienced a large increase in wastewater disposal over the past decade.

"Documenting stress orientations is already challenging in these regions, and characterizing changes in those stresses over time is an even greater challenge," Skoumal said. "In the areas where we have looked though, we haven't seen compelling evidence for significant stress rotations due to wastewater disposal."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

CAMH releases updated national clinical guidelines for treatment of opioid use disorder

2021-07-07

As more evidence emerges that opioid overdose deaths have increased dramatically since the onset of COVID-19, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), in collaboration with subject matter experts and medical regulatory authorities across Canada, have now released updated national clinical guidelines for the treatment of opioid use disorder. END ...

Faulty memories of our past whereabouts: The fallacy of an airtight alibi

2021-07-07

When someone is suspected of criminal activity, one of the most important questions they are asked is if they have a credible alibi. Playing back past events in our minds, however, is not like playing back a video recording. Recollections of locations, dates, and companions can become muddled with the passage of time. If a suspect's memories are out of line with documented events, a once-plausible alibi can crumble and may be seen as evidence of guilt.

To put people's memories of past whereabouts to the test, a team of researchers tracked the locations of 51 volunteers for one month and found that their recollections were wrong approximately 36% of the time.

"This is the first study to examine memory for where ...

New model aims to promote better-adapted bladder cancer treatment in the future

2021-07-07

Uppsala University scientists have designed a new mouse model that facilitates study of factors contributing to the progression of human bladder cancer and of immune-system activation when the tumour is growing. Using this model, they have been able to study how proteins change before, while and after a tumour develops in the bladder wall. The study has now been published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.

"The model was designed both to contain specific oncogenes, as they're called -- mutations that can drive tumour growth -- and to show a high incidence of harmful mutations, which we often see in people who get bladder cancer. These harmful mutations arise because of smoking, for instance, which is ...

Ancient Islamic tombs cluster like galaxies

2021-07-07

Sudanese Islamic burial sites are distributed according to large-scale environmental factors and small-scale social factors, creating a galaxy-like distribution pattern, according to a study published July 7, 2021 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Stefano Costanzo of the University of Naples "L'Orientale" in Italy and colleagues.

The Kassala region of eastern Sudan is home to a vast array of funerary monuments, from the Islamic tombs of modern Beja people to ancient burial mounds thousands of years old. Archaeologists don't expect these monuments are randomly placed; their ...

Mapping urban greenspace use with cellphone GPS data

2021-07-07

GPS data from cell phones may provide insight into how city inhabitants are using their urban greenspaces, in a study published July 7, 2021 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Meghann Mears and Paul Brindley from the University of Sheffield, UK, and colleagues.

Urban greenspaces confer a range of health and well-being benefits on city inhabitants and provide connection to nature. In this study, Mears and colleagues use cellphone GPS data to assess how frequently residents of the city of Sheffield in the UK engage with their local urban greenspaces, and whether this engagement was different across demographic groups.

The authors used the "Shmapped" app, developed as part of the Improving Well-being through Urban Nature project, to track how frequently 240 users based in Sheffield ...

New iguanodon-like dinosaur identified from jawbone fossil from Spain

2021-07-07

New iguanodon-like dinosaur identified from jawbone fossil from Spain was likely a 6-8m long herbivore, closely related to species found in modern-day China and Niger.

INFORMATION:

Article Title: A new Styracosternan hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Early Cretaceous of Portell, Spain

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0253599

...

Brain microstructure may explain benefits of physical activity on older adults' cognition

2021-07-07

Brain microstructure may help explain the benefits of physical activity on cognition in older adults, according to MRI scans of 318 brains post-mortem.

INFORMATION:

Article Title: Physical activity, brain tissue microstructure, and cognition in older adults

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (https://www.nia.nih.gov) grants K25 AG61254 (RJD), K01 AG64044 (VNP), K01 AG50823 (BDJ), R01 AG17917 (DAB), R01 AG47976 (ASB), R01 AG56352 (ASB), R01 AG64233 (JAS, KA), and P30 AG10161 (DAB), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (https://www.ninds.nih.gov) grant UH3 NS100599 ...

Soft shell makes hard ceramic less likely to shatter

2021-07-07

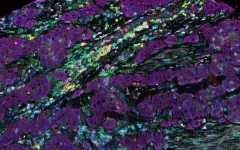

HOUSTON - (July 7, 2021) - A thin shell of soft polymer can help keep knotty ceramic structures from shattering, according to materials scientists at Rice University.

Ceramics made with 3D printers crack under stress like any plate or bowl. But covered in a soft polymer cured under ultraviolet light, the same materials stand a far better chance of keeping their structural integrity, much like a car windshield's treated glass is less likely to shatter.

The research at Rice's Brown School of Engineering, which appears in Science Advances, demonstrates the concept on schwarzites, complex lattices that for decades existed only as theory but can now be made with 3D printers. With added polymers, they come to resemble structures ...

New imaging technique may boost research in biology, neuroscience

2021-07-07

Microscopists have long sought to find a way to produce high-quality, deep-tissue imaging of living subjects in a timely fashion. Until now, they had to choose between image quality or speed when it comes to looking into the inner workings of complex biological systems.

Such a development would have a powerful impact on researchers in biology and in neuroscience, experts say. Now Dushan N. Wadduwage, a John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellow in Imaging at the FAS Center of Advanced Imaging, along with a team from MIT, detailed a new technique that would make that possible in a report in Science Advances.

In the paper, the team presents a new process that uses computational imaging to get high resolution images at a rate 100 to 1,000 times faster than other state-of-the-art ...

Atmospheric acidity impacts oceanic ecology

2021-07-07

Increased acidity in the atmosphere is disrupting the ecological balance of the oceans, according to new research led by the University of East Anglia (UEA).

The first study to look at acidity's impact on nutrient transport to the ocean demonstrates that the way nutrients are delivered affects the productivity of the ocean and its ability to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere.

The research, 'Changing atmospheric acidity as a modulator of nutrient deposition and ocean biogeochemistry', is published today in Science Advances. The analysis was carried out by an international team of experts, sponsored by the United Nations Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP).

Prof Alex Baker, professor of marine and atmospheric chemistry ...