Soft shell makes hard ceramic less likely to shatter

Rice lab shows complex, 3D-printed schwarzites withstand pressure when coated

2021-07-07

(Press-News.org) HOUSTON - (July 7, 2021) - A thin shell of soft polymer can help keep knotty ceramic structures from shattering, according to materials scientists at Rice University.

Ceramics made with 3D printers crack under stress like any plate or bowl. But covered in a soft polymer cured under ultraviolet light, the same materials stand a far better chance of keeping their structural integrity, much like a car windshield's treated glass is less likely to shatter.

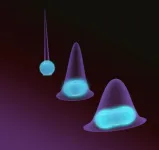

The research at Rice's Brown School of Engineering, which appears in Science Advances, demonstrates the concept on schwarzites, complex lattices that for decades existed only as theory but can now be made with 3D printers. With added polymers, they come to resemble structures found in nature like seashells and bones that consist of hardened platelets in a biopolymer matrix.

Schwarzites, named for German scientist Hermann Schwarz, who hypothesized in the 1880s the "negatively curved" structures could be used wherever very strong but lightweight materials are needed, from batteries to bones to buildings.

The researchers led by Rice materials scientists Pulickel Ajayan and Muhammad Rahman and graduate student and lead author Seyed Mohammad Sajadi proved through experiments and simulations that a coating of polymer no more than 100 microns thick will make fragile schwarzites up to 4.5 times more resistant to catastrophic fractures.

The structures may still crack under pressure, but they won't fall apart.

"We've clearly seen that the uncoated structures are very brittle," said Rahman, a research scientist at Rice. "But when we put the coated structures under compression, they will take the load until they completely break. And interestingly, even then they don't completely break into pieces. They remain enclosed like laminated glass."

The team, with members in Hungary, Canada and India, created computer models of the structures and printed them with a polymer-infused ceramic "ink." The ceramic was cured on the fly by ultraviolet lights in the printer, and then dipped in polymer and cured again.

Along with uncoated control units, the intricate blocks were then subjected to high pressure. The control schwarzites shattered as expected, but the polymer coating prevented cracks from propagating in the others, allowing the structures to keep their form.

The researchers also compared the schwarzites to coated solid ceramics and found the porous structures were inherently tougher.

"The architecture definitely has a role," Sajadi said. "We saw that if we coat a solid structure, the effect of the polymer was not as effective as with the schwarzite."

Ajayan said the coatings acted a bit like the natural materials they mimic, as the polymer infuses defects in the ceramics and enhances their resistance.

Rahman said several structural applications could benefit from polymer-enhanced ceramics. Their biocompatibility could also eventually make them suitable for prosthetics.

"I'm pretty sure that if we can optimize these structures topologically, they also show good promise for use as bioscaffolds," Rahman said.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors are Livia Vasarhelyi, Akos Kukovecz and Zoltan Konya of the University of Szeged, Hungary; Reza Mousavi of ANSYS Inc.; Amir Hossein Rahmati of the University of Houston; Taib Arif and Tobin Filleter of the University of Toronto; Peter Boul of Aramco Americas; Zhenqian Pang and Teng Li of the University of Maryland; Rice alumnus Chandra Shekhar Tiwary of the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, India; and research professor Robert Vajtai of Rice and the University of Szeged.

Ajayan is chair of Rice's Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering, the Benjamin M. and Mary Greenwood Anderson Professor in Engineering and a professor of chemistry.

The research was supported by the Hungarian Research Development and Innovation Office, the Ministry for Innovation and Technology in Hungary and supercomputing resources at the University of Maryland and the Maryland Advanced Research Computing Center.

Read the abstract at XXXXXXXX.

This news release can be found online at news.rice.edu.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Math gets real in strong, lightweight structures: http://news.rice.edu/2017/11/16/math-gets-real-in-strong-lightweight-structures-2/

Theoretical tubulanes inspire ultrahard polymers: http://news.rice.edu/2019/11/13/theoretical-tubulanes-inspire-ultrahard-polymers-2/

Ajayan Research Group: https://ajayan.rice.edu

Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering: https://msne.rice.edu

George R. Brown School of Engineering: https://engineering.rice.edu

VIDEO:

https://youtu.be/ZMPaXY5-C8M

Drop test. (Credit: Courtesy of the Ajayan Research Group/Rice University)

https://youtu.be/oWYyt_5pY44

Compression test. (Credit: Courtesy of the Ajayan Research Group/Rice University)

Image for download:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/06/0628_CERAMIC-1-web.jpg

A compression test of 3D-printed schwarzites either coated or uncoated with a thin polymer shows how the polymer keeps the ceramic from shattering. The materials could be used wherever very strong but lightweight materials are needed. (Credit: Courtesy of the Ajayan Research Group/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,978 undergraduates and 3,192 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-07

Microscopists have long sought to find a way to produce high-quality, deep-tissue imaging of living subjects in a timely fashion. Until now, they had to choose between image quality or speed when it comes to looking into the inner workings of complex biological systems.

Such a development would have a powerful impact on researchers in biology and in neuroscience, experts say. Now Dushan N. Wadduwage, a John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellow in Imaging at the FAS Center of Advanced Imaging, along with a team from MIT, detailed a new technique that would make that possible in a report in Science Advances.

In the paper, the team presents a new process that uses computational imaging to get high resolution images at a rate 100 to 1,000 times faster than other state-of-the-art ...

2021-07-07

Increased acidity in the atmosphere is disrupting the ecological balance of the oceans, according to new research led by the University of East Anglia (UEA).

The first study to look at acidity's impact on nutrient transport to the ocean demonstrates that the way nutrients are delivered affects the productivity of the ocean and its ability to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere.

The research, 'Changing atmospheric acidity as a modulator of nutrient deposition and ocean biogeochemistry', is published today in Science Advances. The analysis was carried out by an international team of experts, sponsored by the United Nations Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP).

Prof Alex Baker, professor of marine and atmospheric chemistry ...

2021-07-07

To create high-resolution, 3D images of tissues such as the brain, researchers often use two-photon microscopy, which involves aiming a high-intensity laser at the specimen to induce fluorescence excitation. However, scanning deep within the brain can be difficult because light scatters off of tissues as it goes deeper, making images blurry.

Two-photon imaging is also time-consuming, as it usually requires scanning individual pixels one at a time. A team of MIT and Harvard University researchers has now developed a modified version of two-photon imaging that can image deeper within tissue and perform the imaging much more quickly than what was previously possible.

This kind of imaging could allow scientists to more rapidly obtain ...

2021-07-07

Metastatic tumors originating from notoriously aggressive triple-negative breast cancer that emerge in the lungs contain a more diverse array of cancer cells than those that arise in the liver, according to a new study in mice and organs from deceased cancer patients. The study also identified a set of genes that distinguish lung and liver metastases; together, the findings may inform future research on how targeted therapies impact tumors across various microenvironments. While scientists have known that the presence of distinct tumor cell populations within the same tumor drives breast cancer progression, it has not been fully understood why this dangerous cellular diversity develops within some tumors and not others. To investigate ...

2021-07-07

From above, the Antarctic Ice Sheet might look like a calm, perpetual ice blanket that has covered Antarctica for millions of years. But the ice sheet can be thousands of meters deep at its thickest, and it hides hundreds of meltwater lakes where its base meets the continent's bedrock. Deep below the surface, some of these lakes fill and drain continuously through a system of waterways that eventually drain into the ocean.

Now, with the most advanced Earth-observing laser instrument NASA has ever flown in space, scientists have improved their maps of these hidden lake systems under the West Antarctic ice sheet--and ...

2021-07-07

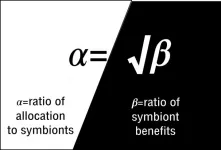

"Equal pay for equal work," a motto touted by many people, turns out to be relevant to the plant world as well. According to new research by Stanford University ecologists, plants allocate resources to their microbial partners in proportion to how much they benefit from that partnership.

"The vast majority of plants rely on microbes to provide them with the nutrients they need to grow and reproduce," explained Brian Steidinger, a former postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Stanford ecologist, Kabir Peay. "The problem is that these microbes differ in how well they do the job. We wanted to see how the plants reward their microbial employees."

In a new study, published July 6 in the journal American Naturalist, the researchers investigated ...

2021-07-07

Very recently, researchers led by Markus Aspelmeyer at the University of Vienna and Lukas Novotny at ETH Zurich cooled a glass nanoparticle into the quantum regime for the first time. To do this, the particle is deprived of its kinetic energy with the help of lasers. What remains are movements, so-called quantum fluctuations, which no longer follow the laws of classical physics but those of quantum physics. The glass sphere with which this has been achieved is significantly smaller than a grain of sand, but still consists of several hundred million atoms. In contrast to ...

2021-07-07

DURHAM, N.C. -- You dash into a convenience store for a quick snack, spot an apple and reach for a candy bar instead. Poor self-control may not be the only factor behind your choice, new research suggests. That's because our brains process taste information first, before factoring in health information, according to new research from Duke University.

"We spend billions of dollars every year on diet products, yet most people fail when they attempt to diet," said study co-author Scott Huettel, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke. "Taste seems to have an advantage that sets us up for failure."

"For many individuals, health information enters the decision process ...

2021-07-07

Injecting sulphur into the stratosphere to reduce solar radiation and stop the Greenland ice cap from melting. An interesting scenario, but not without risks. Climatologists from the University of Liège have looked into the matter and have tested one of the scenarios put forward using the MAR climate model developed at the University of Liège. The results are mixed and have been published in the journal The Cryosphere.

The Greenland ice sheet will lose mass at an accelerated rate throughout the 21st century, with a direct link between anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and the extent of Greenland's mass loss. To combat this phenomenon, and therefore global warming, it is essential to reduce ...

2021-07-07

ITHACA, N.Y. - An interdisciplinary team of Cornell and Harvard University researchers developed a machine learning tool to parse quantum matter and make crucial distinctions in the data, an approach that will help scientists unravel the most confounding phenomena in the subatomic realm.

The Cornell-led project's paper, "Correlator Convolutional Neural Networks as an Interpretable Architecture for Image-like Quantum Matter Data," published June 23 in Nature Communications. The lead author is doctoral student Cole Miles.

The Cornell team was led by Eun-Ah Kim, professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences, who partnered with Kilian Weinberger, associate professor of computing and information science in the Cornell Ann S. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Soft shell makes hard ceramic less likely to shatter

Rice lab shows complex, 3D-printed schwarzites withstand pressure when coated