(Press-News.org) To create high-resolution, 3D images of tissues such as the brain, researchers often use two-photon microscopy, which involves aiming a high-intensity laser at the specimen to induce fluorescence excitation. However, scanning deep within the brain can be difficult because light scatters off of tissues as it goes deeper, making images blurry.

Two-photon imaging is also time-consuming, as it usually requires scanning individual pixels one at a time. A team of MIT and Harvard University researchers has now developed a modified version of two-photon imaging that can image deeper within tissue and perform the imaging much more quickly than what was previously possible.

This kind of imaging could allow scientists to more rapidly obtain high-resolution images of structures such as blood vessels and individual neurons within the brain, the researchers say.

"By modifying the laser beam coming into the tissue, we showed that we can go deeper and we can do finer imaging than the previous techniques," says Murat Yildirim, an MIT research scientist and one of the authors of the new study.

MIT graduate student Cheng Zheng and former postdoc Jong Kang Park are the lead authors of the paper, which appears today in Science Advances. Dushan N. Wadduwage, a former MIT postdoc who is now a John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellow in Imaging at the Center for Advanced Imaging at Harvard University, is the paper's senior author. Other authors include Josiah Boivin, an MIT postdoc; Yi Xue, a former MIT graduate student; Mriganka Sur, the Newton Professor of Neuroscience at MIT; and Peter So, an MIT professor of mechanical engineering and of biological engineering.

Deep imaging

Two-photon microscopy works by shining an intense beam of near-infrared light onto a single point within a sample, inducing simultaneous absorption of two photons at the focal point, where the intensity is the highest. This long-wavelength, low-energy light can penetrate deeper into tissue without damaging it, allowing for imaging below the surface.

However, two-photon excitation generates images by fluorescence, and the fluorescent signal is in the visible spectral region. When imaging deeper into tissue samples, the fluorescent light scatters more and the image becomes blurry. Imaging many layers of tissue is also very time-consuming. Using wide-field imaging, in which an entire plane of tissue is illuminated at once, can speed up the process, but the resolution of this approach is not as great as that of point-by-point scanning.

The MIT team wanted to develop a method that would allow them to image a large tissue sample all at once, while still maintaining the high resolution of point-by-point scanning. To achieve that, they came up with a way to manipulate the light that they shine onto the sample. They use a form of wide-field microscopy, shining a plane of light onto the tissue, but modify the amplitude of the light so that they can turn each pixel on or off at different times. Some pixels are lit up while nearby pixels remain dark, and this predesigned pattern can be detected in the light scattered by the tissue.

"We can turn each pixel on or off by this kind of modulation," Zheng says. "If we turn off some of the spots, that creates space around each pixel, so now we can know what is happening in each of the individual spots."

After the researchers obtain the raw images, they reconstruct each pixel using a computer algorithm that they created.

"We control the shape of the light and we get the response from the tissue. From these responses, we try to resolve what kind of scattering the tissue has. As we do the reconstructions from our raw images, we can get a lot of information that you cannot see in the raw images," Yildirim says.

Using this technique, the researchers showed that they could image about 200 microns deep into slices of muscle and kidney tissue, and about 300 microns into the brains of mice. That is about twice as deep as was possible without this patterned excitation and computational reconstruction, Yildirim says. The technique can also generate images about 100 to 1,000 times faster than conventional two-photon microscopy.

Brain structure

This type of imaging should allow researchers to more rapidly obtain high-resolution images of neurons in the brain, as well as other structures such as blood vessels. Imaging blood vessels in the brains of mice could be particularly useful for learning more about how blood flow is affected by neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Yildirim says.

"All the studies of blood flow or morphology of the blood vessel structures are based on two-photon or three-photon point scanning systems, so they're slow," he says. "By using this technology, we can really perform high-speed volumetric imaging of blood flow and blood vessel structure in order to understand the changes in blood flow."

The technique could also lend itself to measuring neuronal activity, by adding voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes or fluorescent calcium probes that light up when neurons are excited. It could also be useful for analyzing other types of tissue, including tumors, where it could be used to help determine the edges of a tumor.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering P41 program and the NIBIB Pathway to Independence Award, the Hamamatsu Corporation, the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology, the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART), the Center for Advanced Imaging at Harvard University, and the John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellowship Program.

Written by Anne Trafton, MIT News Office

Metastatic tumors originating from notoriously aggressive triple-negative breast cancer that emerge in the lungs contain a more diverse array of cancer cells than those that arise in the liver, according to a new study in mice and organs from deceased cancer patients. The study also identified a set of genes that distinguish lung and liver metastases; together, the findings may inform future research on how targeted therapies impact tumors across various microenvironments. While scientists have known that the presence of distinct tumor cell populations within the same tumor drives breast cancer progression, it has not been fully understood why this dangerous cellular diversity develops within some tumors and not others. To investigate ...

From above, the Antarctic Ice Sheet might look like a calm, perpetual ice blanket that has covered Antarctica for millions of years. But the ice sheet can be thousands of meters deep at its thickest, and it hides hundreds of meltwater lakes where its base meets the continent's bedrock. Deep below the surface, some of these lakes fill and drain continuously through a system of waterways that eventually drain into the ocean.

Now, with the most advanced Earth-observing laser instrument NASA has ever flown in space, scientists have improved their maps of these hidden lake systems under the West Antarctic ice sheet--and ...

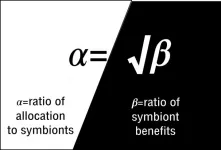

"Equal pay for equal work," a motto touted by many people, turns out to be relevant to the plant world as well. According to new research by Stanford University ecologists, plants allocate resources to their microbial partners in proportion to how much they benefit from that partnership.

"The vast majority of plants rely on microbes to provide them with the nutrients they need to grow and reproduce," explained Brian Steidinger, a former postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Stanford ecologist, Kabir Peay. "The problem is that these microbes differ in how well they do the job. We wanted to see how the plants reward their microbial employees."

In a new study, published July 6 in the journal American Naturalist, the researchers investigated ...

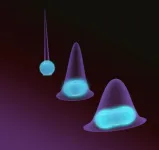

Very recently, researchers led by Markus Aspelmeyer at the University of Vienna and Lukas Novotny at ETH Zurich cooled a glass nanoparticle into the quantum regime for the first time. To do this, the particle is deprived of its kinetic energy with the help of lasers. What remains are movements, so-called quantum fluctuations, which no longer follow the laws of classical physics but those of quantum physics. The glass sphere with which this has been achieved is significantly smaller than a grain of sand, but still consists of several hundred million atoms. In contrast to ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- You dash into a convenience store for a quick snack, spot an apple and reach for a candy bar instead. Poor self-control may not be the only factor behind your choice, new research suggests. That's because our brains process taste information first, before factoring in health information, according to new research from Duke University.

"We spend billions of dollars every year on diet products, yet most people fail when they attempt to diet," said study co-author Scott Huettel, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke. "Taste seems to have an advantage that sets us up for failure."

"For many individuals, health information enters the decision process ...

Injecting sulphur into the stratosphere to reduce solar radiation and stop the Greenland ice cap from melting. An interesting scenario, but not without risks. Climatologists from the University of Liège have looked into the matter and have tested one of the scenarios put forward using the MAR climate model developed at the University of Liège. The results are mixed and have been published in the journal The Cryosphere.

The Greenland ice sheet will lose mass at an accelerated rate throughout the 21st century, with a direct link between anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and the extent of Greenland's mass loss. To combat this phenomenon, and therefore global warming, it is essential to reduce ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - An interdisciplinary team of Cornell and Harvard University researchers developed a machine learning tool to parse quantum matter and make crucial distinctions in the data, an approach that will help scientists unravel the most confounding phenomena in the subatomic realm.

The Cornell-led project's paper, "Correlator Convolutional Neural Networks as an Interpretable Architecture for Image-like Quantum Matter Data," published June 23 in Nature Communications. The lead author is doctoral student Cole Miles.

The Cornell team was led by Eun-Ah Kim, professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences, who partnered with Kilian Weinberger, associate professor of computing and information science in the Cornell Ann S. ...

When you insist you're not racist, you may unwittingly be sending the opposite message.

That's the conclusion of a new study* by three Berkeley Haas researchers who conducted experiments with white participants claiming to hold egalitarian views. After asking them to write statements explaining why they weren't prejudiced against Black people, they found that other white people could nevertheless gauge the writers' underlying prejudice.

"Americans almost universally espouse egalitarianism and wish to see themselves as non-biased, yet racial prejudice persists," says Berkeley ...

A genetic map of an aggressive childhood brain tumour called medulloblastoma has helped researchers identify a new generation anti-cancer drug that can be repurposed as an effective treatment for the disease.

This international collaboration, led by researchers from The University of Queensland's (UQ) Diamantina Institute and WEHI in Melbourne, could give parents hope in the fight against the most common and fatal brain cancer in children.

UQ lead researcher Dr Laura Genovesi said the team had mapped the genetics of these aggressive brain tumours for five years to find new pathways that existing drugs could potentially target.

"These are drugs already approved for other diseases or cancers but have never been tested in paediatric brain tumours," Dr Genovesi ...

ST. LOUIS -- In the United States, low-income and minority students are completing college at low rates compared to higher-income and majority peers -- a detriment to reducing economic inequality. Double-dose algebra could be a solution, according to a new study published in roceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

The paper, "Effects of Double-Dose Algebra on College Persistence and Degree Attainment," is the culmination of a series of studies that followed two cohorts of ninth-grade students over a period of 12 years in the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) where double-dose algebra ...