(Press-News.org) Bahamian mosquitofish in habitats fragmented by human activity are more willing to explore their environment, more stressed by change and have smaller brain regions associated with fear response than mosquitofish from unaffected habitats. The new study from North Carolina State University shows that these fish have adapted quickly in specific ways to human-driven change, and cautions that environmental restoration projects should understand these changes so as not to damage adapted populations.

The Bahamas mosquitofish is a small, coastal fish species that frequently inhabits tidal creeks - shallow, tidally influenced marine ecosystems. In the 1960s and 70s, road construction in The Bahamas caused many of these habitats to become "fragmented," or largely cut off from the ocean.

"Mosquitofish in these fragmented areas suddenly found themselves in a much different environment than previously, in terms of things like predation and tidal dynamics," says Brian Langerhans, associate professor of biology at NC State and corresponding author of the study. "We set out to determine how natural variation in structural habitat complexity and human-induced fragmentation influenced exploratory behavior, stress response, and brain anatomy."

Langerhans and a team of NC State researchers observed about 350 mosquitofish from seven different populations: three fragmented and four non-fragmented. The habitats varied in complexity, from simple mud-bottomed spaces to those that included a large number of rocks and vegetation, such as mangroves.

"We were testing predictions based upon our understanding of natural selection," Langerhans says. "For instance, in a fragmented space with fewer natural predators, we hypothesized that those fish would be more exploratory, since exploratory behavior could be rewarded in terms of competing for food. We also wanted to see if there were physiological changes to the areas of the brain that are associated with those and other similar behaviors."

The team measured stress response and exploratory behavior by temporarily placing mosquitofish in a different environment and observing changes in respiration and their willingness to explore. They also compared brain size in fish from the different habitats.

They found that overall, fish from a more complex environmental habitat were more willing to explore new environments. But for a given level of habitat complexity, fish in fragmented sites were more exploratory than those from unfragmented sites. In addition, fish from fragmented habitats had a higher stress response to change.

"These findings were in line with our expectations," Langerhans says. "Exploratory behavior can reward fish in habitats with few predators by helping them compete for food, and can give fish in complex habitats an advantage in locating safety and hard-to-find food resources. As for the stress response, fish in unfragmented tidal creeks with lots of predators and high tidal dynamics have a higher level of everyday stress than those in more static, predator-free habitats. Change will be much more stressful for fish in the latter areas, since they're less stressed to begin with."

They also noted that while there were no overall differences in brain size between fish from differing habitats, fish from fragmented environments had a smaller telencephalon - the region of the brain associated with fear response, while fish in complex environments had a larger optic tectum and cerebellum, brain regions associated with responding to visual stimuli, motor skills, and associative learning.

"Brain tissue is expensive for an organism to produce," Langerhans says. "If fish in fragmented or simple environments no longer experience major demands for behaviors such as avoiding predation or navigating complex situations, seeing changes in these brain areas isn't that surprising."

The study also highlights how quickly organisms adapt to new environments, and how those environments affect the biological makeup of their inhabitants - something that restoration project planners should keep in mind when attempting to restore habitats to their ancestral state.

"Everything that humans plan to do to these environments should have a lot of forethought put into it," Langerhans says. "If local adaptations occurred over a 50-year period in response to an altered environment and we quickly restore it to 'normal,' you could do more harm than good to some of its inhabitants."

The research appears in the Journal of Animal Ecology, and was supported by NC State's W.M. Keck Center for Behavioral Biology, the Helge Axson Johnson Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council (Grant 2015-00300). NC State graduate student Matthew Jenkins is first author. NC State undergraduates John Cummings and Alex Cabe, fisheries and wildlife professor Nils Peterson, and former NC State postdoctoral researcher Kaj Hulthén, also contributed to the work.

INFORMATION:

Note to editors: An abstract follows.

"Natural and anthropogenic sources of habitat variation influence exploration behaviour, stress response, and brain morphology in a coastal fish"

DOI: 10.1111/1365-2656.13557

Authors: Matthew R. Jenkins, John M. Cummings, Alex R. Cabe, Kaj Hulthén, M. Nils Peterson, R. Brian Langerhans, North Carolina State University

Published: Journal of Animal Ecology

Abstract:

Evolutionary ecology aims to better understand how ecologically important traits respond to environmental heterogeneity. Environments vary both naturally and as a result of human activities, and investigations that simultaneously consider how natural and human-induced environmental variation affect diverse trait types grow increasingly important as human activities drive species endangerment. Here, we examine how habitat fragmentation and structural habitat complexity, affect disparate trait types in Bahamas mosquitofish (Gambusia hubbsi) inhabiting tidal creeks. We tested a priori predictions for how these factors might influence exploratory behaviour, stress reactivity, and brain anatomy. We examined approximately 350 adult Bahamas mosquitofish from seven tidal creek populations across Andros Island, The Bahamas that varied in both human-caused fragmentation (three fragmented, four unfragmented) and natural habitat complexity (e.g. 5-fold variation in rock habitat). Populations that had experienced severe human-induced fragmentation, and thus restriction of tidal exchange from the ocean, exhibited greater exploration of a novel environment, stronger physiological stress responses to a mildly stressful event, and smaller telencephala (relative to body size). These changes matched adaptive predictions based mostly on 1) reduced chronic predation risk and 2) decreased demands for navigating tidally dynamic habitats. Populations from sites with greater structural habitat complexity showed a higher propensity for exploration and a relatively larger optic tectum and cerebellum. These patterns matched adaptive predictions related to increased demands for navigating complex environments. Our findings demonstrate environmental variation, including recent anthropogenic impacts ( END

In 2019, Anaïs Llorens and Athina Tzovara -- one a current, the other a former University of California, Berkeley, postdoctoral scholar at the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute (HWNI) -- were attending a scientific meeting and pleased that one session, on gender bias in academia, attracted nearly a full house. The problem: The audience of some 300 was almost all women.

Where were the men, they wondered? More than 75% of all tenured faculty in Ph.D. programs around the world are men, making their participation key to solving the problem of gender bias, which negatively impacts the careers, work-life balance and mental health of all women in science, and even more ...

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

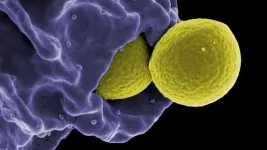

In what turned out to be one of the most important accidents of all time, Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned to his laboratory after a vacation in 1928 to find a clear zone surrounding a piece of mold that had infiltrated a petri dish full of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), a common skin bacterium he was growing.

That region of no bacterial growth was the unplanned birth of a medical miracle, penicillin, and would lead to the era of antibiotics. Now, END ...

When gravitational waves were first detected in 2015 by the advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), they sent a ripple through the scientific community, as they confirmed another of Einstein's theories and marked the birth of gravitational wave astronomy. Five years later, numerous gravitational wave sources have been detected, including the first observation of two colliding neutron stars in gravitational and electromagnetic waves.

As LIGO and its international partners continue to upgrade their detectors' sensitivity to gravitational waves, they will be able to probe a larger volume of the universe, thereby making the detection ...

As the COVID-19 pandemic wanes in the U.S., a new study from the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) and University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC) finds that hospitals nationwide may not be adequately prepared for the next pandemic. A 10-year analysis of hospitals' preparedness for pandemics and other mass casualty events found only marginal improvements in a measurement to assess preparedness during the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was published last month in the Journal of Healthcare Management.

"Our work links objective healthcare data to a hospital score that ...

If a virtual world has ever left you feeling nauseous or disorientated, you're familiar with cybersickness, and you're hardly alone. The intensity of virtual reality (VR)--whether that's standing on the edge of a waterfall in Yosemite or engaging in tank combat with your friends--creates a stomach-churning challenge for 30-80% of users.

In a first-of-its kind study, researchers at the University of Maryland recorded VR users' brain activity using electroencephalography (EEG) to better understand and work toward solutions to prevent cybersickness. The research was conducted by Eric Krokos, who received his Ph.D. in computer science in 2018, and Amitabh Varshney, a professor of computer science ...

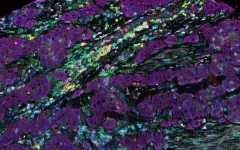

Although wastewater disposal has been the primary driving force behind increased earthquake activity in southern Kansas since 2013, a new study concludes that the disposal has not significantly changed the orientation of stress in the Earth's crust in the region.

Activities like wastewater disposal can alter pore pressure, shape and size within rock layers, in ways that cause nearby faults to fail during an earthquake. These effects are thought to be behind most recent induced earthquakes in the central and eastern United States.

It is possible, however, that human activity could also lead to earthquakes by altering the orientation of stresses that act on faults in the region, said U.S. Geological Survey seismologist ...

As more evidence emerges that opioid overdose deaths have increased dramatically since the onset of COVID-19, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), in collaboration with subject matter experts and medical regulatory authorities across Canada, have now released updated national clinical guidelines for the treatment of opioid use disorder. END ...

When someone is suspected of criminal activity, one of the most important questions they are asked is if they have a credible alibi. Playing back past events in our minds, however, is not like playing back a video recording. Recollections of locations, dates, and companions can become muddled with the passage of time. If a suspect's memories are out of line with documented events, a once-plausible alibi can crumble and may be seen as evidence of guilt.

To put people's memories of past whereabouts to the test, a team of researchers tracked the locations of 51 volunteers for one month and found that their recollections were wrong approximately 36% of the time.

"This is the first study to examine memory for where ...

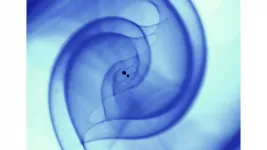

Uppsala University scientists have designed a new mouse model that facilitates study of factors contributing to the progression of human bladder cancer and of immune-system activation when the tumour is growing. Using this model, they have been able to study how proteins change before, while and after a tumour develops in the bladder wall. The study has now been published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.

"The model was designed both to contain specific oncogenes, as they're called -- mutations that can drive tumour growth -- and to show a high incidence of harmful mutations, which we often see in people who get bladder cancer. These harmful mutations arise because of smoking, for instance, which is ...

Sudanese Islamic burial sites are distributed according to large-scale environmental factors and small-scale social factors, creating a galaxy-like distribution pattern, according to a study published July 7, 2021 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Stefano Costanzo of the University of Naples "L'Orientale" in Italy and colleagues.

The Kassala region of eastern Sudan is home to a vast array of funerary monuments, from the Islamic tombs of modern Beja people to ancient burial mounds thousands of years old. Archaeologists don't expect these monuments are randomly placed; their ...