(Press-News.org) Why do some Europeans discriminate against Muslim immigrants, and how can these instances of prejudice be reduced? Political scientist Nicholas Sambanis has spent the last few years looking into this question by conducting innovative studies at train stations across Germany involving willing participants, unknowing bystanders and, most recently, bags of lemons.

His newest study, co-authored with Donghyun Danny Choi at the University of Pittsburgh and Mathias Poertner at Texas A&M University, was published July 8 in the American Journal of Political Science and finds evidence of significant discrimination against Muslim women during everyday interactions with native Germans. That evidence comes from experimental interventions set up on train platforms across dozens of German cities and reveals that discrimination by German women is due to their beliefs that Muslims are regressive with respect to women's rights. In effect, their experiment finds a feminist opposition to Muslims, and shows that discrimination is eliminated when Muslim women signaled that they shared progressive gender attitudes, says Sambanis, who directs the Penn Identity and Conflict Lab (PIC Lab), which he founded when he came to Penn in 2016.

Many studies in psychology have shown bias and discrimination are rooted in a sense that ethnic, racial, or religious differences create distance between citizens, he says. "Faced with waves of immigration from culturally different populations, many Europeans are increasingly supporting policies of coercive assimilation that eliminate those sources of difference by suppressing ethnic or religious marker, for example, by banning the hijab in public places or forcing immigrants to attend language classes," Sambanis says. "Our research shows that bias and discrimination can be reduced via far less coercive measures--as long as immigration does not threaten core values that define the social identities of native populations."

"The Hijab Effect: Feminist Backlash to Muslim Immigrants" is the fourth study in a multiyear project on the topic of how to reduce prejudice against immigrants conducted by Sambanis and the team. The study's co-authors, Choi and Poertner, started working on this project as postdoctoral fellows at the PIC Lab.

The new paper builds on the first leg of the project which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2019 and which explored whether discrimination against immigrants is reduced when immigrants show that they share civic norms that are valued by native citizens. That study found evidence that shared norms reduce but do not eliminate discrimination. The new study explores the impact of norms and ideas that are important to particular subgroups of the native population, and finds stronger effects when such norms are shared by immigrants.

The findings have implications for how to think about reducing conflict between native and immigrant communities in an era of increased cross-border migration, Sambanis says.

He and his co-authors conducted the large-scale field experiment in 25 cities across Germany involving more than 3,700 unknowing bystanders.

"Germany was a good case study because it has received the largest number of asylum applications in Europe since 2015, a result of the refugee crisis created by wars in Syria and other countries in the Middle East and Central Asia," Sambanis says. "Germany has had a long history of immigration from Muslim countries since the early post-war period, and anti-immigrant sentiments have been high as a result of cultural differences. These differences are manipulated politically and become more salient."

The intervention went like this: A woman involved in the study approached a bench at a train station where bystanders waited and drew their attention by asking them if they knew if she could buy tickets on the train.

She then received a phone call and audibly conversed with the caller in German regarding her sister, who was considering whether to take a job or stay at home and take care of her husband and her kids. The scripted conversation revealed the woman's position on whether her sister has the right to work or a duty to stay at home to care for the family.

At the end of the phone call, a bag she was holding seemingly tears, making her drop a bunch of lemons, which scatter on the platform and she appeared to need help gathering them.

In the final step, team members who were not a part of the intervention observed and recorded whether each bystander who was within earshot of the phone call helped the women collect the lemons.

They experimentally varied the identity of the woman, who was sometimes a native German or an immigrant from the Middle East; and the immigrant sometimes wore a hijab to signal her Muslim identity and sometimes not.

They found that men were not very receptive to different messages regarding the woman's attitude toward gender equality, but German women were. Among German women, anti-Muslim discrimination was eliminated when the immigrant woman signaled that she held progressive views vis-à-vis women's rights. Men continued to discriminate in both the regressive and progressive conditions of the experiment.

It was a surprise that the experimental treatment did not seem to make a big difference in the behavior of men towards Muslim women.

"Women were very receptive to this message that we had about Muslims sharing progressive beliefs about women's rights, but men were indifferent to it," says Sambanis. "We expected that there would be a difference, and that the effect of the treatment would be larger among women, but we did not expect that it would be basically zero for men."

The experiment makes gender identity more salient and establishes a common identity between native German women--most of whom share progressive views on gender--and the immigrant women in the progressive condition. This is the basis of the reduction of discrimination, Sambanis says, and it does not require coercive measures like forcing Muslims to take off the hijab. "You can overcome discrimination in other ways, but it is important to signal that that the two groups share a common set of norms and ideas that define appropriate civic behaviors."

The results are surprising from the perspective of the prior literature, which assumed that it is very hard for people to overcome barriers created by race, religion, and ethnicity. At the same time, this experiment speaks to the limits of multiculturalism, says Sambanis. "Our work shows that differences in ethnic, racial, or linguistic traits can be overcome, but citizens will resist abandoning longstanding norms and ideas that define their identities in favor of a liberal accommodation of the values of others," he says.

INFORMATION:

Nicholas Sambanis is a Presidential Distinguished Professor in the School of Arts & Sciences, chair of the Department of Political Science, and director of the Penn Identity and Conflict Lab at the University of Pennsylvania.

For media inquiries, please contact Kristen de Groot, krisde@upenn.edu, 215-756-5563

Plants have microscopically small pores on the surface of their leaves, the stomata. With their help, they regulate the influx of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. They also use the stomata to prevent the loss of too much water and withering away during drought.

The stomatal pores are surrounded by two guard cells. If the internal pressure of these cells drops, they slacken and close the pore. If the pressure rises, the cells move apart and the pore widens.

The stomatal movements are thus regulated by the guard cells. Signalling pathways in these cells are so complex that it is difficult for humans to intervene with them directly. However, researchers of the Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Würzburg in ...

A research team co-led by UCL (University College London) has solved a decades-old mystery as to how Jupiter produces a spectacular burst of X-rays every few minutes.

The X-rays are part of Jupiter's aurora - bursts of visible and invisible light that occur when charged particles interact with the planet's atmosphere. A similar phenomenon occurs on Earth, creating the northern lights, but Jupiter's is much more powerful, releasing hundreds of gigawatts of energy, enough to briefly power all of human civilisation*.

In a new study, published in Science Advances, researchers combined close-up observations of Jupiter's environment by NASA's satellite Juno, which is currently orbiting the planet, with simultaneous X-ray ...

Two factors that play a key role in climate change - increased climate warming and elevated ozone levels - appear to have detrimental effects on soybean plant roots, their relationship with symbiotic microorganisms in the soil and the ways the plants sequester carbon.

The results, published in the July 9 edition of Science Advances, show few changes to the plant shoots aboveground but some distressing results underground, including an increased inability to hold carbon that instead gets released into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas.

North Carolina State University researchers examined the interplay of warming and increased ozone levels with certain important underground organisms - arbuscular ...

A survey offered to transgender and nonbinary people across six continents and in thirteen languages shows that during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many faced reduced access to gender-affirming resources, and this reduction was linked to poorer mental health. Brooke Jarrett of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, and colleagues present the findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on July 9.

Gender-affirming resources, which can include health care such as surgery and/or hormone therapy as well as gender affirming services and products --are well-known to significantly ...

Trust in science - but not trust in politicians or the media - significantly raises support across US racial groups for COVID-19 social distancing.

INFORMATION:

Article Title: The role of race and scientific trust on support for COVID-19 social distancing measures in the United States

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0254127

...

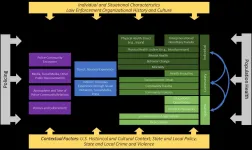

A specific police action, an arrest or a shooting, has an immediate and direct effect on the individuals involved, but how far and wide do the reverberations of that action spread through the community? What are the health consequences for a specific, though not necessarily geographically defined, population?

The authors of a new UW-led study looking into these questions write that because law enforcement directly interacts with a large number of people, "policing may be a conspicuous yet not-well understood driver of population health."

Understanding how law enforcement impacts the mental, physical, social and structural health and wellbeing of a community is a complex challenge, involving many academic and research ...

Meningitis is associated with high mortality and frequently causes severe sequelae. Newborn infants are particularly susceptible to this type of infection; they develop meningitis 30 times more often than the general population. Group B streptococcus (GBS) bacteria are the most common cause of neonatal meningitis, but they are rarely responsible for disease in adults. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur, in collaboration with Inserm, Université de Paris and Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital (AP-HP), set out to explain neonatal susceptibility to GBS meningitis. In a mouse model, they demonstrated that the immaturity of both the gut microbiota and epithelial barriers such as the gut and choroid plexus play a role in the susceptibility of newborn infants to bacterial meningitis caused by ...

The Delta variant was detected for the first time in India in October 2020 and has since spread throughout the world. It is now dominant in many countries and regions (India, the UK, Portugal, Russia, etc.) and is predicted to be the most prevalent variant in Europe within weeks or months. Epidemiological studies have shown that the Delta variant is more transmissible than other variants. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur (CNRS joint unit), in collaboration with Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou (part of the Paris Public Hospital Network or AP-HP), Orléans Regional Hospital and Strasbourg University Hospital, studied the sensitivity of the Delta variant ...

To enable tissue renewal, human tissues constantly eliminate millions of cells, without jeopardizing tissue integrity, form and connectivity. The mechanisms involved in maintaining this integrity remain unknown. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur and the CNRS today revealed a new process which allows eliminated cells to temporarily protect their neighbors from cell death, thereby maintaining tissue integrity. This protective mechanism is vital, and if disrupted can lead to a temporary loss of connectivity. The scientists observed that when the mechanism is deactivated, the simultaneous elimination of ...

New Brunswick, N.J. (July 9, 2021) -- A massive volcanic eruption in Indonesia about 74,000 years ago likely caused severe climate disruption in many areas of the globe, but early human populations were sheltered from the worst effects, according to a Rutgers-led study.

The findings appear in the journal PNAS.

The eruption of the Toba volcano was the largest volcanic eruption in the past two million years, but its impacts on climate and human evolution have been unclear. Resolving this debate is important for understanding environmental changes during a key interval in human evolution.

"We were able to use a large number of climate model simulations to resolve what seemed like a paradox," said lead author Benjamin Black, an assistant professor in the Department ...