'Hydrogel-based flexible brain-machine interface'

The interface is easy to insert into the body when dry, but behaves 'stealthily' inside the brain when wet

2021-07-13

(Press-News.org) A KAIST research team and collaborators revealed a newly developed hydrogel-based flexible brain-machine interface. To study the structure of the brain or to identify and treat neurological diseases, it is crucial to develop an interface that can stimulate the brain and detect its signals in real time. However, existing neural interfaces are mechanically and chemically different from real brain tissue. This causes foreign body response and forms an insulating layer (glial scar) around the interface, which shortens its lifespan.

To solve this problem, the research team of Professor Seongjun Park developed a 'brain-mimicking interface' by inserting a custom-made multifunctional fiber bundle into the hydrogel body. The device is composed not only of an optical fiber that controls specific nerve cells with light in order to perform optogenetic procedures, but it also has an electrode bundle to read brain signals and a microfluidic channel to deliver drugs to the brain.

The interface is easy to insert into the body when dry, as hydrogels become solid. But once in the body, the hydrogel will quickly absorb body fluids and resemble the properties of its surrounding tissues, thereby minimizing foreign body response.

The research team applied the device on animal models, and showed that it was possible to detect neural signals for up to six months, which is far beyond what had been previously recorded. It was also possible to conduct long-term optogenetic and behavioral experiments on freely moving mice with a significant reduction in foreign body responses such as glial and immunological activation compared to existing devices.

"This research is significant in that it was the first to utilize a hydrogel as part of a multifunctional neural interface probe, which increased its lifespan dramatically," said Professor Park. "With our discovery, we look forward to advancements in research on neurological disorders like Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease that require long-term observation."

INFORMATION:

The research was published in Nature Communications on June 8, 2021. (Title: Adaptive and multifunctional hydrogel hybrid probes for long-term sensing and modulation of neural activity) The study was conducted jointly with an MIT research team composed of Professor Polina Anikeeva, Professor Xuanhe Zhao, and Dr. Hyunwoo Yook.

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant for emerging research, Korea Medical Device Development Fund, KK-JRC Smart Project, KAIST Global Initiative Program, and Post-AI Project.

-Publication

Park, S., Yuk, H., Zhao, R. et al. Adaptive and multifunctional hydrogel hybrid probes for long-term sensing and modulation of neural activity. Nat Commun 12, 3435 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23802-9

-About KAIST

KAIST is the first and top science and technology university in Korea. KAIST was established in 1971 by the Korean government to educate scientists and engineers committed to industrialization and economic growth in Korea.

Since then, KAIST and its 67,000 graduates have been the gateway to advanced science and technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship. KAIST has emerged as one of the most innovative universities with more than 10,000 students enrolled in five colleges and seven schools including 1,039 international students from 90 countries.

On the precipice of its semi-centennial anniversary in 2021, KAIST continues to strive to make the world better through its pursuits in education, research, entrepreneurship, and globalization. For more information about KAIST, please visit http://www.kaist.ac.kr/

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-13

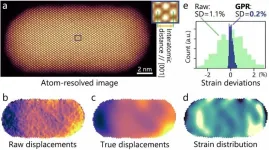

Ishikawa, Japan - Sometimes, a material's property, such as magnetism and catalysis, can change drastically owing to nothing more than minute changes in the separation between its atoms, commonly referred to as "local strains" in the parlance of materials science. A precise measurement of such local strains is, therefore, important to materials scientists.

One powerful technique employed for this purpose is "high-angle annular dark-field imaging" (HAADF), an approach within scanning transmission electron microscopy (a technique for mapping the position of atoms ...

2021-07-13

Museum specimens held in natural history collections around the world represent a wealth of underutilized genetic information due to the poor state of preservation of the DNA, which often makes it difficult to sequence. An international team, led by researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and the Museum of Natural History of the City of Geneva (MHN), has optimized a method developed for analyzing ancient DNA to identify the relationships between species on a deep evolutionary scale. This work is published in the journal Genome Biology and ...

2021-07-13

Australian reptiles face serious conservation threats from illegal poaching fueled by international demand and the exotic pet trade.

In a new study in Animal Conservation, researchers from the University of Adelaide and the Monitor Conservation Research Society (Monitor) investigated the extent of illegal trade in a well-known Australian lizard: the shingleback, also known as the bobtail or sleepy lizard.

Using government records, media reports, and online advertisements, the researchers found clear evidence that many shinglebacks have been illegally poached from the wild and are smuggled overseas to be traded as pets.

Author and PhD Candidate Adam Toomes from the University of Adelaide says: ...

2021-07-13

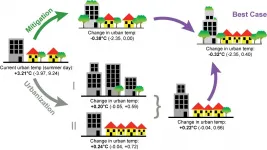

Low-income neighborhoods and communities with higher Black, Hispanic and Asian populations experience significantly more urban heat than wealthier and predominantly white neighborhoods within a vast majority of populous U.S. counties, according new research from the University of California San Diego's School of Global Policy and Strategy.

The analysis of remotely-sensed land surface temperature measurements of 1,056 U.S. counties, which have ten or more census districts, was recently published in the journal END ...

2021-07-13

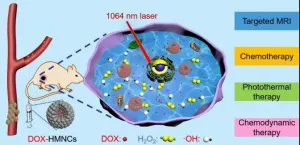

As a minimally invasive method for cancer therapy at precise locations, NIR-induced photothermal therapy (PTT) has drawn extensively attention. The therapeutic mechanism is the use of photothermal agents (PTAs) in the treatment of tumors,and its therapeutic effect happens only at the tumor site where both light-absorbent and localized laser radiation coexist.

The development of PTAs with NIR-II absorbance, ranging from 1000nm to 1700 nm, can efficiently improve their penetrating ability and therapeutic effects because of their high penetration depth in the body. Howerever, several disadvantages are associated with these NIR-II responsive PTAs for their ...

2021-07-13

Over the past years, graphene oxide membranes have been mainly studied for water desalination and dye separation. However, membranes have a wide range of applications such as the food industry. A research group led by Aaron Morelos-Gomez of Shinshu University's Global Aqua Innovation Center investigated the application of graphene oxide membranes for milk which typically creates dense foulant layers on polymeric membranes.

Graphene oxide membranes have the advantage to create a porous foulant layer, therefore, their filtration performance can be maintained better than commercial polymeric membranes. The unique chemical and ...

2021-07-13

Clinician well-being is imperative to providing high-quality patient care, yet clinician burnout continues to increase, especially over the last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Four leading cardiovascular organizations - the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the European Society of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation - are calling for global action to improve clinician well-being in a joint opinion paper published today.

"Over the last several decades, there have been significant changes in health care with the expansion of technology, regulatory burden and clerical task loads. These developments have come at a cost to the ...

2021-07-13

A new population-based study looking at nearly 30 years of billing data demonstrates that sex-based differences in Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) payments exists for Canadian ophthalmologists.

A team led by researchers and clinicians from the Donald K. Johnson Eye Institute, part of the Krembil Research Institute at University Health Network (UHN), studied 22,389 Ontario physicians across three decades and found a significant payment gap between female and male ophthalmologists even after accounting for age, and some practice differences. This disparity was more pronounced among ophthalmologists when compared to other surgical, medical procedural and medical non-procedural specialty groups.

"This is real and robust ...

2021-07-13

DALLAS, July 13, 2021 -- Sharing the results of genetic testing for cardiomyopathy in adolescents ages 13-18 does not appear to cause emotional harm to families or adversely impact family function or dynamics, according to new research published today in Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine, an American Heart Association journal.

Genetic testing for cardiomyopathy in symptomatic children has the potential to confirm a diagnosis, clarify prognosis, determine eligibility for disease-specific cardiomyopathy therapies and even inform risk for other family members. Genetic testing for asymptomatic adults and children also occurs after one of their family members receives positive cardiomyopathy genetic ...

2021-07-13

Philadelphia, July 13, 2021--Adding to the growing body of literature demonstrating the feasibility of correcting lethal genetic diseases before birth, researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have used DNA base editing in a prenatal mouse model to correct a lysosomal storage disease known as Hurler syndrome. Using an adenine base editor delivered in an adeno-associated viral vector, the researchers corrected the single base mutation responsible for the condition, which begins before birth and affects multiple organs, with the potential to cause death in childhood if untreated.

The findings were published ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] 'Hydrogel-based flexible brain-machine interface'

The interface is easy to insert into the body when dry, but behaves 'stealthily' inside the brain when wet