(Press-News.org) Scientists from the University of Graz, Kanzelhöhe Observatory, Skoltech, and the World Data Center SILSO at the Royal Observatory of Belgium, have presented the Catalogue of Hemispheric Sunspot Numbers. It will enable more accurate predictions of the solar cycle and space weather, which can affect human-made infrastructure both on Earth and in orbit. The study came out in the Astronomy & Astrophysics journal, and the catalogue is available from SILSO -- the World Data Center for the production, preservation, and dissemination of the international sunspot number.

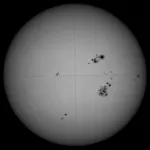

Our Sun is a big boiling ball of gas, most of which is so hot that electrons are ripped off from atoms, creating a circulating mix of charged particles, called plasma. These moving charges endow the Sun with an enormous magnetic field, which bundles up as it rises from the solar interior and creates dark areas known as sunspots on the surface.

Sunspots are the primary sources of solar flares and coronal mass ejections, or CMEs. These are huge magnetic clouds of plasma released from the Sun at great speeds. When directed toward the Earth, they cause powerful magnetic disturbances that can damage the equipment on satellites, incapacitate telecommunications, and even cause blackouts in a city -- with devastating effects on the economy.

The appearance and disappearance of sunspots varies according to a roughly 11-year cycle. It begins with almost no sunspots. As it progresses, more and more spots emerge on the middle latitudes and migrate to the solar equator. Since the Sun's equator rotates faster than the poles, its magnetic field becomes entangled and strengthened in bundles over the course of the cycle. Eventually, the field line bundles become strong enough to get pushed out through the photosphere as loops that trap and eject plasma as CMEs.

Monitoring sunspots is therefore crucial for predicting dangerous space weather events and their effects on air travelers, astronauts, and the equipment and infrastructure -- both on Earth, in orbit, and on long-term space missions.

Initially observed by Galileo in the 17th century, sunspots are now monitored daily by about 80 observatories across the world. The World Data Center SILSO at the Royal Observatory of Belgium is the global hub for all sunspot data. Systematic data on the total count of sunspots is available starting from the 18th century. However, recent models suggest that solar activity is better understood as an interplay between the activities in the northern and the southern hemispheres considered separately. Such data is much more scarce, with the most important solar activity index -- the International Sunspot Number -- only recording sunspot counts by hemisphere since 1992.

The authors of the recent study in Astronomy & Astrophysics came up with a method to greatly extend the available data by reconstructing historical hemispheric sunspot numbers. As a result, they released a continuous catalogue of daily and monthly data of the northern and southern hemispheric sunspot numbers going back to 1874. The team showed its high correspondence to the existing hemispheric data and demonstrated that solar cycle predictions are indeed more accurate when the evolution of sunspot numbers is considered separately for the two hemispheres.

"Our Sun is an intriguing star, and its physics is both simple and complicated. We have learned from our study that we can obtain a better understanding of the long-term evolution of the Sun's activity by simply treating first the two hemispheres separately and only afterwards summing both contributions up to obtain the overall activity. The newly reconstructed data on hemispheric sunspot numbers will be available to the scientific community, and we believe they can provide an important basis to develop new, more accurate prediction schemes of solar activity," said Astrid Veronig, the lead author of the study, professor at the University of Graz, and head of the Kanzelhöhe Observatory for Solar and Environmental Research.

Skoltech graduate student and study co-author Shantanu Jain highlighted the practical utility of the new catalogue: "We believe that this new catalogue will be essential to accurately predict space weather since we now have continuous hemispheric data for a longer period to make meaningful solar cycle predictions. If we were to face extreme solar eruptions in today's age of technological dependency, it could easily knock out our power grids, satellite communications, the internet, and cause economic losses of up to trillions of dollars. An accurate prediction of space weather can help prepare ourselves and avoid such a scenario."

"For permanent technical infrastructures, for long-term issues like ozone depletion or climate, and in view of future long-duration manned space missions to the Moon or Mars, there is a growing need for mid- and long-term forecasts of the trend of solar activity over the next few months or years. As part of an emerging discipline called 'space climate,' such long-term predictions of the strength of the solar cycle can only rest on a detailed knowledge of the actual evolution of many past solar cycles. Our new extended data series is one of the key steps in the growing efforts to revisit and fully exploit legacy data collections using the modern tools of the 21st century," study co-author and the head of the World Data Center SILSO Frédéric Clette commented.

"Currently, we still do not fully understand how the solar dynamo works and how the solar magnetic field is generated during the 11-year solar cycle. All the planets of our solar system orbit around the Sun in a so-called ecliptic plane. It means that observatories on Earth or instruments on board any Earth-orbiting satellite which make images of the Sun never really see what happens on the solar poles. However, in February 2020 a groundbreaking space mission -- the Solar Orbiter -- was launched to fly very close to the Sun. It will perform gravitational maneuvers to reach out of the ecliptic and glimpse at the poles for the first time in history. The first polar pass is expected to take place in March 2025 with the spacecraft reaching an inclination of 17 degrees above the ecliptic plane and increasing to 33 degrees in July 2029. We think that the newly developed product of hemispheric sunspot numbers together with the unprecedented observations and fundamentally new knowledge from the Solar Orbiter will help us to advance solar cycle studies and space weather predictions. And whatever storms may rage, we wish everyone good weather in space," said Tatiana Podladchikova, a co-author of the paper and assistant professor at the Skoltech Space Center.

INFORMATION:

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l3QQQu7QLoM?

A potentially life-saving treatment for heart attack victims has been discovered from a very unlikely source - the venom of one of the world's deadliest spiders.

A drug candidate developed from a molecule found in the venom of the Fraser Island (K'gari) funnel web spider can prevent damage caused by a heart attack and extend the life of donor hearts used for organ transplants.

The discovery was made by a team led by END ...

The research team led by Prof. WEI Haiming and Prof. TIAN Zhigang from Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), collaborating with the research group led by Prof. SUN Zimin from the First Affiliated Hospital of USTC revealed the pathological mechanism of severe pre-engraftment syndrome (PES) after umbilical cord blood transplantation, not only providing a treatment strategy for patients with PES, but significantly guiding for further improvement in the curative effect of unrelated cord blood transplantation (UCBT). This study was published in Nature Communications.

UCBT is an important means to cure hematological ...

In February 2020, a trio of bio-imaging experts were sitting amiably around a dinner table at a scientific conference in Washington, D.C., when the conversation shifted to what was then a worrying viral epidemic in China. Without foreseeing the global disaster to come, they wondered aloud how they might contribute.

Nearly a year and a half later, those three scientists and their many collaborators across three national laboratories have published a comprehensive study in Biophysical Journal that - alongside other recent, complementary studies of coronavirus proteins ...

Russian scientists have synthesized chemical compounds that can stop the degeneration of neurons in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and other severe brain pathologies. These substances can provide a breakthrough in the treatment of neurodegenerative pathologies. New molecules of pyrrolyl- and indolylazine classes activate intracellular mechanisms to combat one of the main causes of "aged" brain diseases - an excess of so-called amyloid structures that accumulate in the human brain with age. The essence of the study was published in the European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. Experts from the Institute of Cytology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Organic Synthesis of the Ural Branch of the Russian ...

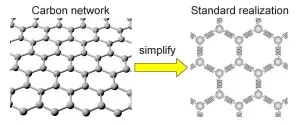

A new mathematical model helps predict the tiny changes in carbon-based materials that could yield interesting properties.

Scientists at Tohoku University and colleagues in Japan have developed a mathematical model that abstracts the key effects of changes to the geometries of carbon material and predicts its unique properties.

The details were published in the journal Carbon.

Scientists generally use mathematical models to predict the properties that might emerge when a material is changed in certain ways. Changing the geometry of three-dimensional (3D) graphene, which is made of networks of carbon atoms, by adding chemicals or introducing topological defects, can improve its catalytic properties, for example. But it has been difficult for scientists to understand why this happens exactly.

The ...

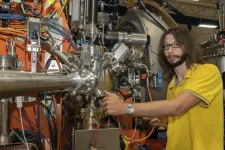

Researchers from the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI and the Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), working in an international team, have developed a new method for complex X-ray studies that will aid in better understanding so-called correlated metals. These materials could prove useful for practical applications in areas such as superconductivity, data processing, and quantum computers. Today the researchers present their work in the journal Physical Review X.

In substances such as silicon or aluminium, the mutual repulsion of electrons hardly affects the material properties. Not so with so-called correlated materials, in which the electrons interact strongly with one another. The movement of one electron in a correlated material leads ...

Prof. LI Chuanfeng, Prof. XU Jinshi and their colleagues from Prof. GUO Guangcan's group, University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), realized the high-contrast readout and coherent manipulation of a single silicon carbide divacancy color center electron spin at room temperature for the first time in the world, in cooperation with Prof. Adam Gali, from the Wigner Research Centre for Physics in Hungary. This work was published in National Science Review on July 5, 2021.

Solid-state spin color centers are of utmost importance in many applications of quantum technologies, the outstanding one among which is the nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center in diamond. Since the detection ...

African swine fever (ASF), first detected in Germany in domestic pigs on 15 July 2021, does not pose a health hazard to humans. "The ASF pathogen cannot be transferred to humans", explains Professor Dr. Dr. Andreas Hensel, President of the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR). "No risk to health is posed by direct contact with diseased animals or from eating food made from infected domestic pigs or wild boar".

The ASF pathogen is a virus which infects domestic pigs and wild boar and which leads to a severe, often lethal, disease in these animals. It is transferred via direct contact or with excretions from infected animals, or through ticks. The ASF virus is endemic to infected wild animals ...

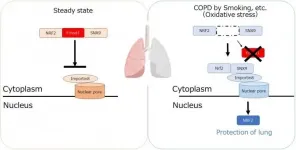

Tokyo, Japan - Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) causes illness and death worldwide. It is characterized by destruction of the walls of tiny air sacs in the lungs, known as emphysema, and a decline in lung function. Little has been known about the mechanisms by which it begins to develop. But now, researchers from Japan have found a protein that promotes the development of the early stages of emphysema, with the potential to be a therapeutic target.

COPD can be triggered by environmental factors such as cigarette smoking that result in lung inflammation. The development of inflammation involves the movement ...

WINSTON-SALEM, NC, JULY 19, 2021 -- Wake Forest researchers and clinicians are using patient-specific tumor 'organoid' models as a preclinical companion platform to better evaluate immunotherapy treatment for appendiceal cancer, one of the rarest cancers affecting only 1 in 100,000 people. Immunotherapies, also known as biologic therapies, activate the body's own immune system to control, and eliminate cancer.

Appendiceal cancer is historically resistant to systemic chemotherapy, and the effect of immunotherapy is essentially unknown because clinical trials are difficult to perform due to lack of ...