(Press-News.org) EAST LANSING, Mich. - Tens of millions of patients around the world suffer from persistent and potentially life-threatening wounds. These chronic wounds, which are also a leading cause of amputation, have treatments, but the cost of existing wound dressings can prevent them from reaching people in need.

Now, a Michigan State University researcher is leading an international team of scientists to develop a low-cost, practical biopolymer dressing that helps heal these wounds.

"The existing efficient technologies are far too expensive for most health care systems, greatly limiting their use in a timely manner," said Morteza Mahmoudi, an assistant professor in the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine and the Precision Health Program. "An economically accessible, practical and effective technology is needed."

To develop that new technology, Mahmoudi tapped into years of experience and expertise, having studied advanced materials to heal heart tissue, fight infections and support immune systems. But the team also kept an eye on cost, working to develop a product that could be made available to as many patients as possible, even in resource constrained markets.

"My goal is always to make something that works and is practical," Mahmoudi said. "I want to see my research become clinical products that help patients."

With his latest work, published July 19 in the journal Molecular Pharmaceutics, Mahmoudi is getting closer to that goal. He's working with partners in the United Kingdom who have started a company to oversee the development and approval of the new technology.

"We are building an experienced and expert team in the U.K. who will be able to efficiently commercialize the dressing," Mahmoudi said. "The company has just won a very competitive Eurostar grant to accelerate product development."

Working with his collaborators, Mahmoudi conducted a small pilot trial of the wound dressing with 13 patients with chronic wounds, all of whom were cured, he said.

Patients with advanced chronic wounds -- those which do not respond to traditional therapies -- are estimated to number over 45 million globally, making this one of the world's most pressing and urgent health care needs, Mahmoudi said.

The United States is home to about 5% of this population, yet more than 90% of the sales of "active" wound care technologies happen in the U.S. That essentially means that the rest of the world is left out, Mahmoudi said.

Venous leg ulcers and pressure ulcers associated with immobility in older and paralyzed patients are also major causes of chronic wounds, but perhaps the best-known examples of this type of injury being diabetic foot ulcers. Worldwide, there are more than 400 million people living with diabetes, and some studies have estimated that up to a quarter of those patients will develop foot ulcers within their lifetime.

Even with the high level of care available in the U.S., more than 30% of patients who develop a diabetic foot ulcer will die within five years of its onset. For reference, that percentage is higher than breast cancer, prostate cancer and colon cancer.

Diabetic foot ulcers also illustrate many of the reasons why chronic wounds can be so challenging to treat.

Patients with diabetes can be dealing with restricted blood flow and other factors that slow their immune response, compromising the body's ability to heal the wound on its own. They can also have nerve damage that dulls the wound's pain and can delay patients from seeking treatment. When wounds heal more slowly and stay open longer, bacteria have more opportunities to cause infections and lead to serious complications. Put bluntly, there's a lot going wrong in a chronic wound.

"Chronic wounds are some of the most complicated things doctors have to treat," Mahmoudi said. "If you want to make a dressing that works, it has to address all those problems. And in order to be relevant to the majority of patients in the world, it has to be easy to use, practical and inexpensive as well."

There are many technologies available to support healing in chronic wounds, but those that can stimulate tissue regeneration are typically derived from harvested natural tissues. This is complex and expensive, resulting in products that cost upwards of $1,000, putting them out of reach for many patients and health care systems.

To attack those problems, Mahmoudi drew on a wealth of experience in developing new materials for biomedical applications. By designing a product that can be manufactured from readily available biopolymers, production costs can be kept low, and the team could add various other materials to lead to improved healing.

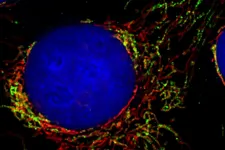

The team starts with a flexible framework of nanofibers -- exceedingly thin threads -- of natural polymers, including collagen, a structural-support protein found in our skin and cartilage. The framework provides a three-dimensional scaffold that fosters cell migration and the development of new blood vessels, essentially replicating the function of the extracellular matrix, the natural support system found in healthy, living tissue.

"It's important that the physical and mechanical properties of the dressing are really close to that of skin," Mahmoudi said. "In order to heal, the new cells have to feel like they're at home."

To that framework, the team can incorporate proteins, peptides and nanoparticles that not only spur the growth of new cells and blood vessels but also fight off bacteria by encouraging a patient's own immune system to join the charge. (The team's experiences on these elements were documented in earlier publications in Nature Nanotechnology and Trends in Biotechnology).

The dressing also degrades over time, meaning that nobody would have to change or remove it and potentially aggravate the wound site. And at roughly $20 apiece, Mahmoudi believes that the dressings -- if and when approved by regulatory agencies -- will be affordable to even resource-strapped health care systems faced with treating these serious wounds.

Although there are many existing wound care products, Mahmoudi is optimistic that the new dressing will stand out thanks to its low cost, high performance and another piece of research he did years ago.

For this previous project, though, he wasn't developing any new technology. He was interviewing hundreds of health care workers around the U.S., asking them what they wanted and needed in a wound dressing.

"We developed this dressing to solve the problems they were having. One of the clinicians told me, 'When you see too many products on the market, that means none of them works,'" said Mahmoudi, a Spartan driven to make things that work.

INFORMATION:

More than 20 researchers joined Mahmoudi on this project, representing about 15 different research institutions, including Harvard Medical School; Emory University; Georgia Tech; Rutgers State University; McGill University; University of Siegen in Germany; and the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

(Note for reporters, the research paper is available here: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00400)

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) launched a new online tool that could more quickly advance medical discoveries to reverse progressive hearing loss. The tool enables easy access to genetic and other molecular data from hundreds of technical research studies involving hearing function and the ear. The research portal called gene Expression Analysis Resource (gEAR) was unveiled in a study last month in Nature Methods. It is operated by a group of physician-scientists at the UMSOM Institute for Genome Sciences (IGS) in collaboration with their colleagues at other institutions.

The portal allows researchers to rapidly access data and provides easily interpreted visualizations of datasets. Scientists can also input ...

New Curtin University-led research has called into question existing health advice that mothers wait a minimum of two years after giving birth to become pregnant again, in order to reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm and small-for-gestational age births.

The research found that a World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation to wait at least 24 months to conceive after a previous birth may be unnecessarily long for mothers in high-income countries such as Australia, Finland, Norway and the United States.

Lead researcher ...

Errors in the metabolic processes of mitochondria are responsible for a variety of diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. Scientists needed to find out just how the necessary building blocks are imported into the complex biochemical apparatus of these cell areas. The TOM complex (translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane) is considered the gateway to the mitochondrion, the proverbial powerhouse of the cell. The working group headed by Professor Chris Meisinger at the Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Freiburg has now demonstrated - in human cells - how signaling molecules control this gate. A signaling protein called DYRK1A modifies the molecular machinery of TOM and makes it more permeable ...

Three decades ago, child development researchers found that low-income children heard tens of millions fewer words in their homes than their more affluent peers by the time they reached kindergarten. This "word gap" was and continues to be linked to a socioeconomic disparity in academic achievement.

While parenting deficiencies have long been blamed for the word gap, new research from the University of California, Berkeley, implicates the economic context in which parenting takes place -- in other words, the wealth gap.

The findings, published this month in the journal Developmental Science, provide the first evidence that parents may talk less to their kids when experiencing financial scarcity.

"We were interested in what happens when parents think about or experience financial scarcity ...

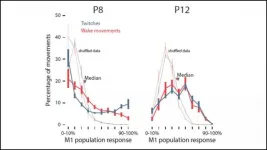

Electrical activity in the motor cortex of rats transforms from redundant to complex over the span of four days shortly after birth. Sleep twitches guide this metamorphosis, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

Despite its name, the motor cortex doesn't control movement right off the bat. Early in development, this part of the brain is solely a sensory structure. Feedback from self-generated movements -- sleep twitches in particular -- may build representations of the body that will later orchestrate movement.

To characterize this transition, Glanz et al. recorded electrical activity from the motor cortex of rat pups eight and 12 days after birth while monitoring their behavior. ...

Politicians may have good reason to turn to angry rhetoric, according to research led by political scientists from Colorado--the strategy seems to work, at least in the short term.

In a new study, Carey Stapleton at the University of Colorado Boulder and Ryan Dawkins at the U.S. Air Force Academy discovered that political furor may spread easily: Ordinary citizens can start to mirror the angry emotions of the politicians they read about in the news. Such "emotional contagion" might even drive some voters who would otherwise tune out of politics to head to the polls.

"Politicians want to get reelected, and anger is a powerful tool that they can use to make that happen," said Stapleton, who recently earned his PhD in political science at ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Did you know multiple sclerosis (MS) means multiple scars? New research shows that the brain and spinal cord scars in people with MS may offer clues to why they developprogressive disability but those with related diseases where the immune system attacks the central nervous system do not.

In a study published in Neurology, Mayo Clinic researchers and colleagues assessed if inflammation leads to permanent scarring in these three diseases:

MS.

Aquaporin-4 antibody positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (AQP4-NMOSD).

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody associated disorder (MOGAD).

They also studied whether scarring may be a reason for ...

For decades, researchers around the world have searched for ways to use solar power to generate the key reaction for producing hydrogen as a clean energy source -- splitting water molecules to form hydrogen and oxygen. However, such efforts have mostly failed because doing it well was too costly, and trying to do it at a low cost led to poor performance.

Now, researchers from The University of Texas at Austin have found a low-cost way to solve one half of the equation, using sunlight to efficiently split off oxygen molecules from water. The finding, published recently in Nature Communications, represents a step forward toward greater adoption ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Plants are DNA hoarders. Adhering to the maxim of never throwing anything out that might be useful later, they often duplicate their entire genome and hang on to the added genetic baggage. All those extra genes are then free to mutate and produce new physical traits, hastening the tempo of evolution.

A new study shows that such duplication events have been vitally important throughout the evolutionary history of gymnosperms, a diverse group of seed plants that includes pines, cypresses, sequoias, ginkgos and cycads. Published today in Nature Plants, the research indicates that ...

FINDINGS

A chemical modification that occurs in some RNA molecules as they carry genetic instructions from DNA to cells' protein-making machinery may offer protection against non-alcoholic fatty liver, a condition that results from a build-up of fat in the liver and can lead to advanced liver disease, according to a new study by UCLA researchers.

The study, conducted in mice, also suggests that this modification -- known as m6A, in which a methyl group attaches to an RNA chain -- may occur at a different rate in females than it does in males, potentially explaining why females tend to have higher fat content in the liver. The researchers found that without the m6A modification, differences in liver fat content between the sexes were reduced dramatically.

In ...