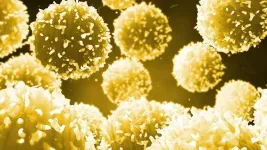

(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - The parasites that cause severe malaria are well-known for the sinister ways they infect humans, but new research may lead to drugs that could block one of their most reliable weapons: interference with the immune response.

In the study, scientists defined the atomic-level architecture of the connection between a protein on the surface of a parasite-infected red blood cell when it binds to a receptor on the surface of an immune cell.

When that protein-receptor connection is made under normal circumstances, the infected red blood cell, hijacked by the disease-causing parasite, de-activates the immune cell - meaning the body won't fight the infection. A drug designed to fit into that space could block the interaction, allowing the immune system to get to work clearing away the pathogen.

In a previous study, a team including the Ohio State University and National Institutes of Health scientists who led this research did similar work with another immune cell receptor that the protein, called RIFIN, binds to in its bid to suppress the immune response.

Through a genome-wide analysis of the parasite that causes malaria, the scientists found RIFIN exerts the same type of immune-suppressing function in various species of Plasmodium infecting humans, gorillas and chimpanzees. This suggests it is a mechanism that has not changed over the course of evolution - meaning this function is critical to the parasite's success and therefore an attractive target for intervention.

The researchers envision either a vaccine or a chemical compound, or both, could be developed to disable this function, reducing the risk of severe malaria cases that require hospitalization and rapid treatment.

"RIFIN targets two receptors to down-regulate immune function so the parasite can evade immune surveillance and survive. If we can lift the immunosuppression, the human immune system can take care of the rest," said Kai Xu, assistant professor of veterinary biosciences at Ohio State and co-lead author of the study. "Inhibition of the immune response is one of the major reasons severe malaria infection is so hard to deal with."

Xu co-led the research with Peter Kwong of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Vaccine Research Center.

The study is published in Nature Communications.

This work focuses on species of Plasmodium that cause the worst cases of malaria - many of the 200 million people infected annually have mild symptoms, but severe cases can cause respiratory distress and organ failure. More than 400,000 people die of the disease each year. There are several drugs used to treat malaria, but current medications are losing effectiveness because the parasites have developed resistance to them.

Humans are infected through the bite of a mosquito carrying the parasite. Once in the human body, the parasites transform themselves in the liver so they can then infect red blood cells, reproduce and release toxic factors, which leads to clinical symptoms of disease.

The members of the RIFIN family of parasitic proteins - of which there are 200-plus - can do lots of things to exacerbate the infection once the parasite has reached red blood cells. A small subset of them bind to two receptors, LAIR1 and LILRB1, on B-, T- and NK cell surfaces to keep those immune cells dormant.

Capturing the protein-receptor interactions with X-ray crystallography in enough detail to define the precise structure at the binding site can be tricky because they happen so quickly and are dynamic. The researchers observed the connections as they naturally happen, but a bit of serendipity provided them with an even better option. It turns out that antibodies induced in some people who have had malaria contain genes from the LAIR1 receptor, and by being part of a parasite-specific antibody, the LAIR1 segment develops a very high attraction to RIFIN. Using those unusual antibody structures to observe the LAIR1 segment's attachment to RIFIN gave the team a much, much closer look at the structure of their bond.

From here, the researchers plan to focus their efforts on the 20 or so RIFIN family members that are attracted to and bind with the two immune cell receptors.

"RIFIN is a large and diverse parasitic protein family. However, the subset of RIFIN molecules that bind to LAIR1 and LILRB1 is less diversified and shares common features, so we only focus on that small subset," Xu said. "We want to generate a drug that can specifically target the receptor-binding interface on RIFIN, blocking one of the important immune escape mechanisms of the parasite. That's the future direction."

INFORMATION:

This work was funded by the NIAID Vaccine Research Center, a GenScript Innovation grant and the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research. The researchers also used the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science's Advanced Photon Source.

Contact: Kai Xu, Xu.4692@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, Caldwell.151@osu.edu

LA JOLLA, CA--You can't make a banana split without bananas. And you can't generate stable regulatory T cells without Vitamin C or enzymes called TET proteins, it appears.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) help control inflammation and autoimmunity in the body. Tregs are so important, in fact, that scientists are working to generate stable induced Tregs (iTregs) in vitro for use as treatments for autoimmune diseases as well as rejection to transplanted organs. Unfortunately, it has proven difficult to find the right molecular ingredients to induce stable iTregs.

Now scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology ...

DALLAS, July 21, 2021 -- Babies who were breastfed, even for a few days, had lower blood pressure as toddlers and these differences in blood pressure may translate into improved heart and vascular health as adults, according to new research published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open access journal of the American Heart Association.

Research has found that cardiovascular disease risk factors, including high blood pressure, can start in childhood. Studies have also confirmed breastfeeding is associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk in adulthood. However, the amount and length of time breastfeeding that is needed ...

DALLAS, July 21, 2021 -- People who made even small increases in their daily physical activity levels after receiving an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) experienced fewer incidences of hospitalization and had a decreased risk of death, according to new research published today in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, an American Heart Association journal.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators, also known as ICDs, are battery-powered devices placed under the skin that can detect abnormal heart rhythms and deliver an electric shock to restore a normal heartbeat. According to American Heart Association's Heart Disease ...

An international collaboration elucidates the mechanisms that facilitate accurate identification of moving images. The findings have been published in Nature Communications

Imagine meeting a friend on the street, and imagine that with every step they take, your visual system has to process their image from scratch in order to recognize them. Now imagine if the same thing were to happen for every object and creature that moves around us. We would live in a constant state of uncertainty and inconsistency. Luckily, that is not the case. Our visual system is able to retain information obtained in motion, thereby presenting us with a more consistent picture of our surroundings. These ...

Older adults may be slower to learn actions and behaviours that benefit themselves, but new research shows they are just as capable as younger people of learning behaviours that benefit others.

Researchers at the Universities of Birmingham and Oxford found that youngsters, in contrast, tend to learn much faster when they are making choices that benefit themselves.

The study, published in Nature Communications, focused on reinforcement learning - a fundamental type of learning in which we make decisions based on the positive outcomes from earlier choices. It allows us to adapt our choices to our environment by learning the associations between choices and their outcomes.

Dr Patricia Lockwood is senior author on ...

Every day, people are exposed to a variety of synthetic chemicals through the products they use or the food they eat. For many of these chemicals, the health effects are unknown. Now END ...

New research published in the European Journal of Clinical Investigation identifies cardiovascular test results that might help to identify patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who face an especially high risk of dying.

Out of 1,401 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 admitted to seven Italian centers, 226 (16.1%) underwent transthoracic echocardiography within 48 hours of admission. In-hospital death occurred in 68 patients (30.1%). Low left ventricular ejection fraction, low tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, and acute respiratory distress syndrome were independently associated with in-hospital mortality.

"Clinical ...

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in the Western world. New research published in the Journal of Leukocyte Biology reveals that certain protein markers may indicate which patients have stable forms of CLL and which have more aggressive types.

Identifying these proteins may not only help determine patients' prognoses but also point to potential therapeutic targets for investigators who are searching for new CLL treatments.

"The results offer a meaningful biological approach into the protein composition of CLL cells at an early stage of the disease, when the clinical characteristics of patients are similar and the course of the disease is difficult to predict. ...

The COVID-19 pandemic has strongly impacted our sleep and dream activity. In a recent study published in the Journal of Sleep Research, people had a higher number of awakenings, a harder time falling asleep, higher dream recall, and more lucid dreams during lockdown than after lockdown.

People also reported more dreams related to "being in crowded places" during post-lockdown than lockdown.

For the study, 90 adults in Italy recorded their dream experiences and completed a sleep-dream diary each morning.

"Our results... confirmed that both sleep and ...

The frequency of misattributed paternity, where the assumed father is not the biological father, is low and decreasing in Sweden, according to an analysis of 1.95 million family units with children born mainly between 1950 and 1990.

In the Journal of Internal Medicine analysis, the overall rate of misattributed paternity was 1.7%, with rates closer to 1% in more recent decades.

The authors note that beyond its general scientific and societal relevance, the frequency of misattributed paternity has implications for studies on hereditary conditions. The study's findings indicate that misattributed paternity is unlikely to have large effects on such studies.

"Using simple but elegant methods, together with large-scale ...