(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- A new approach to treating breast cancer kills 95-100% of cancer cells in mouse models of human estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancers and their metastases in bone, brain, liver and lungs. The newly developed drug, called ErSO, quickly shrinks even large tumors to undetectable levels.

Led by scientists at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, the research team reports the findings in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"Even when a few breast cancer cells do survive, enabling tumors to regrow over several months, the tumors that regrow remain completely sensitive to retreatment with ErSO," said U. of I. biochemistry professor David Shapiro, who led the research with Illinois chemistry professor Paul Hergenrother. "It is striking that ErSO caused the rapid destruction of most lung, bone and liver metastases and dramatic shrinkage of brain metastases, since tumors that have spread to other sites in the body are responsible for most breast cancer deaths," Shapiro said.

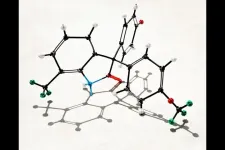

The activity of ErSO depends on a protein called the estrogen receptor, which is present in a high percentage of breast tumors. When ErSO binds to the estrogen receptor, it upregulates a cellular pathway that prepares cancer cells for rapid growth and protects them from stress. This pathway, called the anticipatory Unfolded Protein Response, or a-UPR, spurs the production of proteins that protect the cell from harm.

"The a-UPR is already on, but running at a low level, in many breast cancer cells," Shapiro said. "It turns out that this pathway shields cancer cells from being killed off by anti-cancer drugs."

Shapiro and former U. of I. medical scholar Neal Andruska first identified the a-UPR pathway in 2014 and reported the development of a compound that pushed the a-UPR pathway into overdrive to selectively kill estrogen-receptor-containing breast cancer cells.

"Because this pathway is already on in cancer cells, it's easy for us to overactivate it, to switch the breast cancer cells into lethal mode," said graduate student Darjan Duraki, who shares first-author status on the new report with graduate student Matthew Boudreau.

While the original compound prevented breast cancer cells from growing, it did not rapidly kill them, and it had undesirable side effects. For the new research, Shapiro and Hergenrother worked together on a search for a much more potent small molecule that would target the a-UPR. Their analysis led to the discovery of ErSO, a small molecule that had powerful anticancer properties without detectable side effects in mice, further tests revealed.

"This anticipatory UPR is estrogen-receptor dependent," Hergenrother said. "The unique thing about this compound is that it doesn't touch cells that lack the estrogen receptor, and it doesn't affect healthy cells - whether or not they have an estrogen receptor. But it's super-potent against estrogen-receptor-positive cancer cells."

ErSO is nothing like the drugs that are commonly used to treat estrogen-receptor-positive cancers, Shapiro said.

"This is not another version of tamoxifen or fulvestrant, which are therapeutically used to block estrogen signaling in breast cancer," he said. Even though it binds to the same receptor that estrogen binds, it targets a different site on the estrogen receptor and attacks a protective cellular pathway that is already turned on in cancer cells, he said.

"Since about 75% of breast cancers are estrogen-receptor positive, ErSO has potential against the most common form of breast cancer," Boudreau said. "The amount of estrogen receptor needed for ErSO to target a breast cancer is very low, so ErSO may also work against some breast cancers not traditionally considered to be ER-positive."

Further studies in mice showed that exposure to the drug had no effect on their reproductive development. And the compound was well tolerated in mice, rats and dogs given doses much higher than required for therapeutic efficacy, the researchers found.

ErSO also worked quickly, even against advanced, human-derived breast cancer tumors in mice, the researchers report. Often within a week of exposure to ErSO, advanced human-derived breast cancers in mice shrank to undetectable levels.

"Many of these breast cancers shrink by more than 99% in just three days," Shapiro said. "ErSO is fast-acting and its effects on breast cancers in mice are large and dramatic."

The pharmaceutical company Bayer AG has licensed the new drug and will explore its potential for further study in human clinical trials targeting estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancers, the researchers said. The researchers will next explore whether ErSO is effective against other types of cancers that contain estrogen receptor.

INFORMATION:

Study co-authors at the U. of I. also include veterinary clinical medicine professor Timothy Fan, molecular and integrative physiology professor Erik Nelson, and professor emeritus of pathology Edward Roy. Fan, Hergenrother, Nelson, Shapiro and Roy are affiliates of the Cancer Center at Illinois. Fan, Hergenrother and Nelson also are affiliated with the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at Illinois and Hergenrother and Fan are faculty in the Carle Illinois College of Medicine at the U. of I.

Funders of this work include the University of Illinois, the U.S. Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, and Systems Oncology. The U. of I. has filed patents on some compounds described in the study.

Editor's notes:

To reach David Shapiro, email djshapir@illinois.edu.

To reach Paul Hergenrother, email hergenro@illinois.edu.

The paper "A small-molecule activator of the unfolded protein response eradicates human breast tumors in mice" is available online and from the U. of I. News Bureau.

DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf1383

Unlike the rest of the body, there is not enough real estate in the brain for stored energy. Instead, the brain relies on the hundreds of miles of blood vessels within it to supply fresh energy via the blood. Yet, how the brain expresses a need for more energy during increased activity and then directs its blood supply to specific hot spots was, until now, poorly understood.

Now, University of Maryland School of Medicine and University of Vermont researchers have shown how the brain communicates to blood vessels when in need of energy, and how these blood vessels respond by relaxing or constricting to direct blood flow to specific brain regions.

In their new paper, published on July 21 in Science Advances, ...

Every year, Santa Ana Winds drive some of the largest wildfires in Southern California during autumn and winter, and a new analysis of 71 years of data suggests that the total amount of land burned is determined more by wind speed and power line ignitions than by temperature and precipitation. The findings suggest that maintaining utility lines and carefully planning urban growth to reduce powerline ignitions may help to reduce future losses from Santa Ana-driven autumn and winter fires, which occur far less frequently than summer fires but account for the largest blazes annually. While California's summer fires are typically driven by an abundance of fuels such as dry twigs and logs, and are often ignited by lightning in remote areas, the state's autumn and winter fires are typically ...

To be useful, drones need to be quick. Because of their limited battery life they must complete whatever task they have - searching for survivors on a disaster site, inspecting a building, delivering cargo - in the shortest possible time. And they may have to do it by going through a series of waypoints like windows, rooms, or specific locations to inspect, adopting the best trajectory and the right acceleration or deceleration at each segment.

Algorithm outperforms professional pilots

The best human drone pilots are very good at doing this and have so far always outperformed autonomous systems in drone racing. Now, a research group at the University of Zurich (UZH) has created an algorithm that can find the quickest ...

Commonly accepted advice to keep a straight back and squat while lifting in order to avoid back pain has been challenged by new Curtin University research.

The research examined people who had regularly performed manual lifting through their occupation for more than five years and found those who experienced low back pain as a result were more likely to use the recommended technique of squatting and keeping a straight back, while those without back pain tended not to adhere to the recommended lifting advice.

Lead researcher PhD candidate Nic Saraceni from the Curtin School of Allied Health said the study required participants to each perform 100 lifts using two differently weighted boxes, with researchers ...

Every brain function, from standing up to deciding what to have for dinner, involves neurons interacting. Studies focused on neuronal interactions extend across domains in neuroscience, primarily using the approaches of spike count correlation or dimensionality reduction. Pioneering research from Carnegie Mellon University has identified a way to bridge these approaches, resulting in a richer understanding of neuronal activity.

Neurons use electrical and chemical signals to relay information throughout the body, and we each have billions of them. Understanding how neurons interact with each other is important, ...

Imagine opening up a book of nature photos only to see a kaleidoscope of graceful butterflies flutter out from the page.

Such fanciful storybooks might soon be possible thanks to the work of a team of designers and engineers at CU Boulder's ATLAS Institute. The group is drawing from new advancements in the field of soft robotics to develop shape-changing objects that are paper-thin, fast-moving and almost completely silent.

The researchers' early creations, which they've dubbed "Electriflow," include origami cranes that can bend their necks, flower petals ...

Alexandria, Va., USA - IADR President Pamela Den Besten presented and chaired the IADR President's Symposium "Enamel Defects as Biomarkers for Exposure to Environmental Stressors" at the virtual 99th General Session & Exhibition of the International Association for Dental Research (IADR), held in conjunction with the 50th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Dental Research (AADR) and the 45th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Association for Dental Research (CADR), on July 21-24, 2021.

Enamel pathologies may result from mutations of genes involved in amelogenesis, or from specific environmental ...

Alexandria, Va., USA - Muthuthanthrige Cooray, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan, presented the oral session "Oral and General Health Associations Using Machine Learning Prediction Algorithms" at the virtual 99th General Session & Exhibition of the International Association for Dental Research (IADR), held in conjunction with the 50th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Dental Research (AADR) and the 45th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Association for Dental Research (CADR), on July 21-24, 2021.

General health and oral health are conventionally treated as separate entities within the healthcare delivery, however most general health and oral health problems share common ...

In the race to combat climate change, capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions has been touted as a simple road to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. While the science behind carbon capture is sound, current technologies are expensive and not optimized for all settings. A cover story in Chemical & Engineering News, the weekly newsmagazine of the American Chemical Society, highlights the current state of carbon capture and work being done to improve the process.

Although efficiency improvements and renewable power sources can help, they are often expensive and will not be enough to counter the billions of tons of CO2 sent into the atmosphere each year, writes Associate ...

URBANA, Ill. - When kids sit down to eat lunch at school, fruits and vegetables may not be their first choice. But with more time at the lunch table, they are more likely to pick up those healthy foods. If we want to improve children's nutrition and health, ensuring longer school lunch breaks can help achieve those goals, according to research from the University of Illinois.

"Ten minutes of seated lunch time or less is quite common. Scheduled lunch time may be longer, but students have to wait in line to get their food. And sometimes lunch periods are shared with recess. This means the amount of time children actually have to eat their meals is much less than the scheduled time," says ...