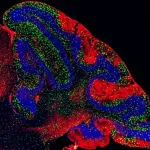

(Press-News.org) Efforts to understand cardiac disease progression and develop therapeutic tissues that can repair the human heart are just a few areas of focus for the Feinberg research group at Carnegie Mellon University. The group's latest dynamic model, created in partnership with collaborators in the Netherlands, mimics physiologic loads on engineering heart muscle tissues, yielding an unprecedented view of how genetics and mechanical forces contribute to heart muscle function.

"Our lab has been working for a long time on engineering and building human heart muscle tissue, so we can better track how disease manifests and also, create therapeutic tissues to one day repair and replace heart damage," explains Adam Feinberg, a professor of biomedical engineering and materials science and engineering. "One of the challenges is that we have to build these small pieces of heart muscle in a petri dish, and we've been doing that for many years. What we've realized is that these in-vitro systems do not accurately recreate the mechanical loading we see in the real heart due to blood pressure."

Hemodynamic loads, or the preload (stretch on heart muscle during chamber filling) and afterload (when the heart muscle contracts), are important not only for healthy heart muscle function, but can also contribute to cardiac disease progression. Preload and afterload can lead to maladaptive changes in heart muscle, as is the case of hypertension, myocardial infarction, and cardiomyopathies.

In new research published in Science Translational Medicine, the group introduces a system comprised of engineered heart muscle tissue (EHT) that is attached to an elastic strip designed to mimic physiologic preloads and afterloads. This first-of-its-kind model shows that recreating exercise-like loading drives formation of more functional heart muscle that is better organized and generates more force each time it contracts. However, using cells from patients with certain types of heart disease, these same exercise-like loads can result in heart muscle dysfunction.

"One of the really important things about this work is that it's a collaborative effort between our lab and collaborators in the Netherlands, including Cardiologist Peter van der Meer," says Feinberg. "Peter treats patients that have genetically-linked cardiovascular disease, including a type called arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) that often becomes worse with exercise. We have been able to get patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells, differentiate these into heart muscle cells, and then use these in our new EHT model to recreate ACM in a petri dish, so we can better understand it."

Jacqueline Bliley, a biomedical engineering graduate student and co-first author of the recently published paper, adds, "The collaborative nature of this work is so important, to be able to ensure reproducibility of the research and compare findings across the world."

Looking to the future, the collaborators aim to use their model and findings to study a wide range of other heart diseases with genetic mutations, develop new therapeutic treatments and test drugs to gauge their effectiveness.

"We can take lessons learned from building the EHT in a dish to create larger pieces of heart muscle that could be used therapeutically. By combining these new results with our previous work involving 3D bioprinting heart muscle ( END

Dynamic heart model mimics hemodynamic loads, advances engineered heart tissue technology

2021-07-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers find immune component to rare neurodegenerative disease

2021-07-21

UT Southwestern researchers have identified an immune protein tied to the rare neurodegenerative condition known as Niemann-Pick disease type C. The END ...

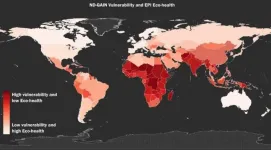

New study confirms relationship between toxic pollution, climate risks to human health

2021-07-21

For more than 30 years, scientists on the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have focused on human-induced climate change. Their fifth assessment report led to the Paris Agreement in 2015 and, shortly after, a special report on the danger of global warming exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The Nobel Prize-winning team stressed that mitigating global warming "would make it markedly easier to achieve many aspects of sustainable development, with greater potential to eradicate poverty and reduce inequalities."

In a first-of-its-kind study that combines assessments of the risks of toxic emissions (e.g., fine particulate matter), ...

Exoskeletons have a problem: They can strain the brain

2021-07-21

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Exoskeletons - wearable devices used by workers on assembly lines or in warehouses to alleviate stress on their lower backs - may compete with valuable resources in the brain while people work, canceling out the physical benefits of wearing them, a new study suggests.

The study, published recently in the journal Applied Ergonomics, found that when people wore exoskeletons while performing tasks that required them to think about their actions, their brains worked overtime and their bodies competed with the exoskeletons rather than working in harmony with them. The study indicates that exoskeletons may place enough burden on the brain that potential benefits to the body are negated.

"It's almost like dancing with a really bad partner," said ...

New approach eradicates breast cancer in mice

2021-07-21

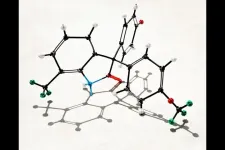

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- A new approach to treating breast cancer kills 95-100% of cancer cells in mouse models of human estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancers and their metastases in bone, brain, liver and lungs. The newly developed drug, called ErSO, quickly shrinks even large tumors to undetectable levels.

Led by scientists at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, the research team reports the findings in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"Even when a few breast cancer cells do survive, enabling tumors to regrow over several months, the tumors that regrow remain completely ...

Study finds calcium precisely directs blood flow in the brain

2021-07-21

Unlike the rest of the body, there is not enough real estate in the brain for stored energy. Instead, the brain relies on the hundreds of miles of blood vessels within it to supply fresh energy via the blood. Yet, how the brain expresses a need for more energy during increased activity and then directs its blood supply to specific hot spots was, until now, poorly understood.

Now, University of Maryland School of Medicine and University of Vermont researchers have shown how the brain communicates to blood vessels when in need of energy, and how these blood vessels respond by relaxing or constricting to direct blood flow to specific brain regions.

In their new paper, published on July 21 in Science Advances, ...

Powerline failures and wind speeds are strongest drivers of land area burned by Santa Ana wind fires

2021-07-21

Every year, Santa Ana Winds drive some of the largest wildfires in Southern California during autumn and winter, and a new analysis of 71 years of data suggests that the total amount of land burned is determined more by wind speed and power line ignitions than by temperature and precipitation. The findings suggest that maintaining utility lines and carefully planning urban growth to reduce powerline ignitions may help to reduce future losses from Santa Ana-driven autumn and winter fires, which occur far less frequently than summer fires but account for the largest blazes annually. While California's summer fires are typically driven by an abundance of fuels such as dry twigs and logs, and are often ignited by lightning in remote areas, the state's autumn and winter fires are typically ...

New algorithm flies drones faster than human racing pilots

2021-07-21

To be useful, drones need to be quick. Because of their limited battery life they must complete whatever task they have - searching for survivors on a disaster site, inspecting a building, delivering cargo - in the shortest possible time. And they may have to do it by going through a series of waypoints like windows, rooms, or specific locations to inspect, adopting the best trajectory and the right acceleration or deceleration at each segment.

Algorithm outperforms professional pilots

The best human drone pilots are very good at doing this and have so far always outperformed autonomous systems in drone racing. Now, a research group at the University of Zurich (UZH) has created an algorithm that can find the quickest ...

Study finds lifting advice doesn't stand up for everyone

2021-07-21

Commonly accepted advice to keep a straight back and squat while lifting in order to avoid back pain has been challenged by new Curtin University research.

The research examined people who had regularly performed manual lifting through their occupation for more than five years and found those who experienced low back pain as a result were more likely to use the recommended technique of squatting and keeping a straight back, while those without back pain tended not to adhere to the recommended lifting advice.

Lead researcher PhD candidate Nic Saraceni from the Curtin School of Allied Health said the study required participants to each perform 100 lifts using two differently weighted boxes, with researchers ...

Take two: Integrating neuronal perspectives for richer results

2021-07-21

Every brain function, from standing up to deciding what to have for dinner, involves neurons interacting. Studies focused on neuronal interactions extend across domains in neuroscience, primarily using the approaches of spike count correlation or dimensionality reduction. Pioneering research from Carnegie Mellon University has identified a way to bridge these approaches, resulting in a richer understanding of neuronal activity.

Neurons use electrical and chemical signals to relay information throughout the body, and we each have billions of them. Understanding how neurons interact with each other is important, ...

Origami comes to life with new shape-changing materials

2021-07-21

Imagine opening up a book of nature photos only to see a kaleidoscope of graceful butterflies flutter out from the page.

Such fanciful storybooks might soon be possible thanks to the work of a team of designers and engineers at CU Boulder's ATLAS Institute. The group is drawing from new advancements in the field of soft robotics to develop shape-changing objects that are paper-thin, fast-moving and almost completely silent.

The researchers' early creations, which they've dubbed "Electriflow," include origami cranes that can bend their necks, flower petals ...