Scientists now understand that these transformations are powered by enzymes - protein molecules comprised of chains of amino acids that act to speed up, or catalyze, the conversion of one kind of molecule (substrates) into another (products). In so doing, they enable reactions such as digestion and fermentation - and all of the chemical events that happen in every one of our cells - that, left alone, would happen extraordinarily slowly.

"A chemical reaction that would take longer than the lifetime of the universe to happen on its own can occur in seconds with the aid of enzymes," said Polly Fordyce, an assistant professor of bioengineering and of genetics at Stanford University.

While much is now known about enzymes, including their structures and the chemical groups they use to facilitate reactions, the details surrounding how their forms connect to their functions, and how they pull off their biochemical wizardry with such extraordinary speed and specificity are still not well understood.

A new technique, developed by Fordyce and her colleagues at Stanford and detailed this week in the journal Science, could help change that. Dubbed HT-MEK -- short for High-Throughput Microfluidic Enzyme Kinetics -- the technique can compress years of work into just a few weeks by enabling thousands of enzyme experiments to be performed simultaneously. "Limits in our ability to do enough experiments have prevented us from truly dissecting and understanding enzymes," said study co-leader Dan Herschlag, a professor of biochemistry at Stanford's School of Medicine.

By allowing scientists to deeply probe beyond the small "active site" of an enzyme where substrate binding occurs, HT-MEK could reveal clues about how even the most distant parts of enzymes work together to achieve their remarkable reactivity.

"It's like we're now taking a flashlight and instead of just shining it on the active site we're shining it over the entire enzyme," Fordyce said. "When we did this, we saw a lot of things we didn't expect." Enzymatic tricks

HT-MEK is designed to replace a laborious process for purifying enzymes that has traditionally involved engineering bacteria to produce a particular enzyme, growing them in large beakers, bursting open the microbes and then isolating the enzyme of interest from all the other unwanted cellular components. To piece together how an enzyme works, scientists introduce intentional mistakes into its DNA blueprint and then analyze how these mutations affect catalysis.

This process is expensive and time consuming, however, so like an audience raptly focused on the hands of a magician during a conjuring trick, researchers have mostly limited their scientific investigations to the active sites of enzymes. "We know a lot about the part of the enzyme where the chemistry occurs because people have made mutations there to see what happens. But that's taken decades," Fordyce said.

But as any connoisseur of magic tricks knows, the key to a successful illusion can lie not just in the actions of the magician's fingers, but might also involve the deft positioning of an arm or the torso, a misdirecting patter or discrete actions happening offstage, invisible to the audience. HT-MEK allows scientists to easily shift their gaze to parts of the enzyme beyond the active site and to explore how, for example, changing the shape of an enzyme's surface might affect the workings of its interior.

"We ultimately would like to do enzymatic tricks ourselves," Fordyce said. "But the first step is figuring out how it's done before we can teach ourselves to do it." Enzyme experiments on a chip

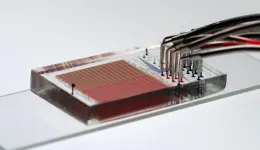

HT-MEK combines two existing technologies to rapidly speed up enzyme analysis. The first is microfluidics, which involves molding polymer chips to create microscopic channels for the precise manipulation of fluids. "Microfluidics shrinks the physical space to do these fluidic experiments in the same way that integrated circuits reduced the real estate needed for computing," Fordyce said. "In enzymology, we are still doing things in these giant liter-sized flasks. Everything is a huge volume and we can't do many things at once."

The second is cell-free protein synthesis, a technology that takes only those crucial pieces of biological machinery required for protein production and combines them into a soupy extract that can be used to create enzymes synthetically, without requiring living cells to serve as incubators.

"We've automated it so that we can use printers to deposit microscopic spots of synthetic DNA coding for the enzyme that we want onto a slide and then align nanoliter-sized chambers filled with the protein starter mix over the spots," Fordyce explained.

Because each tiny chamber contains only a thousandth of a millionth of a liter of material, the scientists can engineer thousands of variants of an enzyme in a single device and study them in parallel. By tweaking the DNA instructions in each chamber, they can modify the chains of amino acid molecules that comprise the enzyme. In this way, it's possible to systematically study how different modifications to an enzyme affects its folding, catalytic ability and ability to bind small molecules and other proteins.

When the team applied their technique to a well-studied enzyme called PafA, they found that mutations well beyond the active site affected its ability to catalyze chemical reactions -- indeed, most of the amino acids, or "residues," making up the enzyme had effects.

The scientists also discovered that a surprising number of mutations caused PafA to misfold into an alternate state that was unable to perform catalysis. "Biochemists have known for decades that misfolding can occur but it's been extremely difficult to identify these cases and even more difficult to quantitatively estimate the amount of this misfolded stuff," said study co-first author Craig Markin, a research scientist with joint appointments in the Fordyce and Herschlag labs.

"This is one enzyme out of thousands and thousands," Herschlag emphasized. "We expect there to be more discoveries and more surprises." Accelerating advances

If widely adopted, HT-MEK could not only improve our basic understanding of enzyme function, but also catalyze advances in medicine and industry, the researchers say. "A lot of the industrial chemicals we use now are bad for the environment and are not sustainable. But enzymes work most effectively in the most environmentally benign substance we have -- water," said study co-first author Daniel Mokhtari, a Stanford graduate student in the Herschlag and Fordyce labs.

HT-MEK could also accelerate an approach to drug development called allosteric targeting, which aims to increase drug specificity by targeting beyond an enzyme's active site. Enzymes are popular pharmaceutical targets because of the key role they play in biological processes. But some are considered "undruggable" because they belong to families of related enzymes that share the same or very similar active sites, and targeting them can lead to side effects. The idea behind allosteric targeting is to create drugs that can bind to parts of enzymes that tend to be more differentiated, like their surfaces, but still control particular aspects of catalysis. "With PafA, we saw functional connectivity between the surface and the active site, so that gives us hope that other enzymes will have similar targets," Markin said. "If we can identify where allosteric targets are, then we'll be able to start on the harder job of actually designing drugs for them."

The sheer amount of data that HT-MEK is expected to generate will also be a boon to computational approaches and machine learning algorithms, like the Google-funded AlphaFold project, designed to deduce an enzyme's complicated 3D shape from its amino acid sequence alone. "If machine learning is to have any chance of accurately predicting enzyme function, it will need the kind of data HT-MEK can provide to train on," Mokhtari said.

Much further down the road, HT-MEK may even allow scientists to reverse-engineer enzymes and design bespoke varieties of their own. "Plastics are a great example," Fordyce said. "We would love to create enzymes that can degrade plastics into nontoxic and harmless pieces. If it were really true that the only part of an enzyme that matters is its active site, then we'd be able to do that and more already. Many people have tried and failed, and it's thought that one reason why we can't is because the rest of the enzyme is important for getting the active site in just the right shape and to wiggle in just the right way."

Herschlag hopes that adoption of HT-MEK among scientists will be swift. "If you're an enzymologist trying to learn about a new enzyme and you have the opportunity to look at 5 or 10 mutations over six months or 100 or 1,000 mutants of your enzyme over the same period, which would you choose?" he said. "This is a tool that has the potential to supplant traditional methods for an entire community."

INFORMATION:

Fordyce is a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and an executive committee member of Stanford ChEM-H. Herschlag is member of Bio-X and the Stanford Cancer Institute, and a faculty fellow of ChEM-H. Other Stanford co-authors include Fanny Sunden, Mason Appel, Eyal Akiva, Scott Longwell and Chiara Sabatti.

The research was funded by Stanford Bio-X, Stanford ChEM-H, the Stanford Medical Scientist Training Program, the National Institutes of Health, the Joint Initiative for Metrology in Biology, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.