(Press-News.org) NEWPORT, Ore. – As sea ice declines in the Arctic, bowhead whales are staying north of the Bering Strait more frequently, a shift that could affect the long-term health of the bowhead population and impact the Indigenous communities that rely on the whales, a new study by Oregon State University researchers shows.

Bowhead whales found in the Pacific Arctic, sometimes called Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort bowheads based on their migratory patterns, normally winter in the northern Bering Sea and migrate north in the spring through the Bering Strait to the Canadian Beaufort Sea, where they spend summer and fall. They then migrate south again through the Strait for the winter.

The migration essentially follows the sea ice south through the Bering Strait, which would close up as ice formed in the Chukchi Sea. But warming temperatures in the Arctic over the past decade have led to sea ice decline and kept the Bering Strait open increasingly into the winter months, said the study’s lead author, Angela Szesciorka, a research associate with Oregon State’s Marine Mammal Institute.

“The lack of ice means they are losing this critical habitat, and as a result, we’re seeing that these whales are not leaving the Arctic anymore for the winter,” Szesciorka said. “Without that ice, there could be changes in bowhead availability for the Indigenous people who rely on the whales. The lack of ice also opens the door for other species to move into the Arctic, resulting in competition for resources, potential predation and increased human interaction due to ship strikes or entanglement in fishing gear.”

The findings were just published in the journal Movement Ecology.

Bowhead whales are a species of baleen whale and the only one that lives year-round in Arctic and subarctic waters; the subarctic is the region just south of the Arctic. They use their large skulls to break through sea ice up to 18 inches thick, feed on zooplankton such as copepods and krill, and can reach up to 200,000 pounds and 62 feet in length. They are believed to have a lifespan of up to 200 years.

Commercial whaling in the 1800s and early 1900s decimated the population found in the Pacific Arctic, and bowheads have been listed as endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act since the 1970s. The species has rebounded to about 25,000 whales across four populations in the Arctic, including the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort group studied by the researchers.

“That group is largest of the four bowhead populations and it appears to be growing,” said co-author Kathleen Stafford, an associate professor at the Marine Mammal Institute, part of OSU’s College of Agricultural Sciences and based at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport.

Sea ice is believed to play an important role in the bowheads’ survival. Slow-moving animals may use sea ice as shelter from potential predators, and the ice-covered water might also lend itself to improved communication among the individuals, Stafford said.

But in the Arctic, sea ice has decreased about 13% per decade since 1979, and near surface air temperatures have risen four times faster than the global average in that time. Once perennial, the sea ice in the Chukchi is now considered annual – meaning the ice is no longer surviving through the melt season.

To better understand what that means for bowhead whales, Szesciorka and Stafford analyzed 11 years of recordings of bowhead whale calls and songs to track how the whales’ movements have changed as sea ice has declined.

The recordings, made between 2009 and 2021, were collected using passive acoustic monitoring devices placed in the Chukchi Sea near the entrance of the Bering Strait. The devices also captured noise from passing vessels.

“Bowheads make a number of non-singing calls, but in the fall, winter and into spring, they are singing,” Szesciorka said. “We think it’s the males who are singing, and that the songs are for courtship purposes. They sing many different songs and they don’t tend to repeat. It’s beautifully complex.”

Analysis of the whales’ calls and songs, coupled with information about sea ice and weather conditions, indicated that the bowheads’ fall migration to the Bering Sea was delayed in years when there was less sea ice and that some whales are wintering instead in the southern Chukchi Sea.

“The Strait is the only gateway between the Arctic and the Pacific – anything going between the two has to pass through there, like a turnstile,” Stafford said. “Not all of the bowheads are passing through this turnstile anymore.”

The researchers also found that spring northward migration was earlier in years when there was less sea ice. Indigenous Traditional Knowledge also suggests that less ice and more open water has shifted the timing of the spring migration by about a month. Those changing migration patterns could impact the Indigenous communities that rely on bowhead whales for nutritional, cultural and spiritual subsistence, the researchers said.

“Bowheads have been hunted for millennia by Arctic peoples, but in the fall of 2019, there were no whales in reach of Indigenous hunters in Utqiagvik, Alaska,” Stafford said. “That has the potential to decrease food security in these communities, and that is problematic.”

The lack of sea ice also means that the “turnstile” at the Bering Strait is open to potential predators such as killer whales and to commercial vessels that have not previously overlapped into bowhead whale territory in the winter.

“There are some big questions for future study: Will bowheads be at increased risk of ship strikes or fishing gear entanglement if the lack of sea ice leads to increased fishing or other ship traffic? Bowheads aren’t typically around vessels, and they may not know how to respond,” Szesciorka said.

“This change is happening very quickly, and it is unclear what the potential impacts might be as the Arctic continues to warm.”

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs.

END

As sea ice declines in the Arctic, bowhead whales are adjusting their migration patterns

2023-02-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UBC's Daniel Pauly and Rashid Sumaila win Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement

2023-02-22

Two courageous UBC ocean fisheries experts - marine biologist Dr. Daniel Pauly and fisheries economist Dr. Rashid Sumaila — have been awarded the 2023 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement.

The award, administered by the University of Southern California, has often been described as the ‘Nobel Prize for the Environment.’

Both are University Killam Professors at the University of British Columbia, and long-time colleagues at its Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. They said that winning this ...

MD Anderson Research Highlights for February 22, 2023

2023-02-22

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

Recent developments include a new understanding of how HPV drives cancer development, a combination therapy to overcome treatment resistance in mantle cell lymphoma, novel ...

Early Cretaceous shift in the global carbon cycle affected both land and sea

2023-02-22

Scientists continue to refine techniques for understanding present-day changes in Earth’s environmental systems, but the planet’s distant past also offers crucial information to deepen that understanding. A geological study by University of Nebraska–Lincoln scientist Matt Joeckel and colleagues provides such information.

Scientific research in recent decades has confirmed that major changes in the global carbon cycle caused significant changes in the Earth’s atmosphere and oceans 135 million years ago, during the early Cretaceous Period. A range of questions remain about the ...

Discovery of massive early galaxies defies prior understanding of the universe

2023-02-22

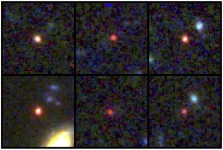

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Six massive galaxies discovered in the early universe are upending what scientists previously understood about the origins of galaxies in the universe.

“These objects are way more massive than anyone expected,” said Joel Leja, assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State, who modeled light from these galaxies. “We expected only to find tiny, young, baby galaxies at this point in time, but we’ve discovered galaxies as mature as our own in what was previously understood to be the dawn of the universe.”

Using the first dataset released from NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, ...

Mechanisms underlying autoimmunity in Down syndrome revealed

2023-02-22

New York, NY (February 22, 2023) – Scientists at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York have identified which parts of the immune system go awry and contribute to autoimmune diseases in individuals with Down syndrome. The findings published in the February 22 online issue of Nature [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05736-y].

The work adds to the research team’s findings published in the journal Immunity in October 2022, showing that people with Down syndrome have less frequent but more severe viral infections.

Studying lab specimens from volunteers with Down syndrome, the investigators identified cytokines and a B cell subtype—key ...

Patients identified as frail before surgery less likely to die one year after

2023-02-22

PITTSBURGH, Feb. 22, 2023 – New research published today in JAMA Surgery shows that when frail patients are connected to resources, including conversations with a physician about possible outcomes and help preparing their body for surgery, they are less likely to die one year after surgery.

While age can be an important indicator of a patient’s likelihood of encountering adverse outcomes or complications of surgery, it does not provide a full picture of their health. Frailty considers the patient’s overall well-being, including their physical and cognitive abilities, as well as their body’s ability to recover from surgery.

“Frailty ...

Association of pandemic with unsafe living situations, intimate partner violence among pregnant individuals

2023-02-22

About The Study: This study found an overall increase in unstable and/or unsafe living situations and intimate partner violence (IPV) between January 2019 and December 2020, with a temporary increase associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. It may be useful for emergency response plans to include IPV safeguards for future pandemics. These findings suggest the need for prenatal screening for unsafe and/or unstable living situations and IPV coupled with referral to appropriate support services and preventive ...

Incidence of aggressive end-of-life care among older adults with metastatic cancer in nursing homes and community settings

2023-02-22

About The Study: The results of this study suggest that despite increased emphasis to reduce aggressive end-of-life care in the past several decades, such care remains common among older persons with metastatic cancer and is slightly more prevalent among nursing home residents than their community-dwelling counterparts. Multilevel interventions to decrease aggressive end-of-life care should target the main factors associated with its prevalence, including hospital admissions in the last 30 days of life and in-hospital death.

Authors: Siran M. Koroukian, Ph.D., of the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, is the corresponding ...

Rising river temperatures hold important clues about climate and other human impacts

2023-02-22

An improved global understanding of river temperature could provide an important barometer for climate change and other human activities.

River temperature is the fundamental water quality measure that regulates physical, chemical and biological processes in flowing waters and, in turn, impacts ecosystems, human health, and industrial, domestic and recreational uses by people.

In a comment piece in the new journal, Nature Water, researchers led by the University of Birmingham, UK, and Indiana University, USA, have called for an increased ...

Human body proven to predict mealtimes

2023-02-22

The human body can predict the timing of regular meals, according to a new study from the University of Surrey. The research team also found that daily blood glucose rhythms may be driven not only by meal timing but by meal size.

In the first study of its kind, researchers from Surrey, led by Professor Jonathan Johnston, investigated if the human circadian system anticipates large meals. Circadian rhythms/systems are physiological changes, including metabolic, that follow a 24-hour cycle and are usually synchronised to environmental signals, such as light and dark cycles.

Previous ...