(Press-News.org) Africa, where humans first evolved, today remains a place of remarkable diversity. Diving into that variation, a new analysis of 180 indigenous Africans from a dozen ethnically, culturally, geographically, and linguistically varied populations by an international scientific team offers new insights into human history and biology, and may inform precision medicine approaches of the future.

The work clarifies human migration histories, both historical and more recent, and provides genetic evidence of adaptation to local environments, manifested through traits such as skin color, heart and kidney development, immunity, and bone growth.

The findings, published in the journal Cell and led by University of Pennsylvania researchers, also have implications for understanding health conditions common in people of African ancestry. And, because African populations have been underrepresented in genomic studies, the investigation significantly expands what is known about human genetic diversity. The investigation turns up millions of new genomic variants known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—differences in one “letter” of the DNA sequence—including many that appear to play roles in health, laying the groundwork for a broader swath of people to benefit from precision medicine based on individual differences.

“There is a lack of knowledge about genomic variation in African populations, particularly in ethnically diverse populations,” says Sarah Tishkoff, a Penn Integrates Knowledge University professor at Penn and senior author on the work. “We focus on populations who practice more traditional lifestyles, live in remote areas that can be difficult to access, and some of whom have never been studied from this perspective before.”

Origins and migrations

Researchers obtained complete genome sequences for 180 individuals—15 from each of 12 indigenous populations. The study is the first to perform rigorous whole-genome sequencing of such a genetically diverse mix of African groups.

“From the perspective of an African physician-scientist, our work demonstrates the importance of long-term scientific collaborations and highlights the urgent need to include more African populations in genetic studies,” says Alfred Njamnshi, a professor at Cameroon’s University of Yaoundé I and a study coauthor. “If all humans came out of Africa, as increasing evidence suggests, it would simply be expected that more effort and resources will be put into studying human genetics in Africans, so as to better understand not only human genetics but human physiology and pathology in general, the basis for more precise human medicine.”

The 12 populations practice, or practiced until recently, traditional livelihoods: farming, livestock herding, or hunting and gathering. Together, they include representatives from each of the four different language families present in Africa: Afroasiatic, Nilo-Saharan, Niger-Congo, and Khoesan.

Placing the new genome sequences from these African populations in context with other, previously sequenced genomes from populations across the globe, the research team crafted a worldwide family tree.

“Inferring African demographic history is very challenging because the history is so complex,” Tishkoff says. “But, with our models, based on shared patterns of genomic variation, you can infer when populations shared a common ancestor, even when accounting for gene flow—populations migrating in and out and interbreeding.”

When the team allowed for gene flow in their models, they found that the southern African Khoesan-speaking group, the San, as well as Central African, rainforest-dwelling hunter-gatherers appeared at the root of the tree. “That’s a very novel result,” Tishkoff says. Previous analyses had pointed to only the San as descending from the most ancient populations.

They also found that the San and Central Africa hunter-gatherer groups split from one another, and from other known populations, more than 200,000 years ago.

Population ancestry models turned up evidence of a now-extinct “ghost” population that may have intermixed with other groups at the time. “We don’t have ancient DNA from fossils because they don’t preserve well in an African environment, but one explanation is there could have been mixing with an archaic population,” Tishkoff says.

The findings add support to linguistics-backed theories of population structure. Linguists have debated whether Khoesan-speaking groups—whose languages share click consonants but are highly distinct in their other features—were truly closely related. According to genomic results, though these groups diverged tens of thousands of years ago, there is evidence that all of them may have shared a common origin in East Africa, and shared more recent gene flow, during the last 10,000 years.

“What we propose is that there may have been an East African origin for these click-speaking groups, and maybe even the rainforest hunter-gatherers as well, though they’ve since lost their original language and adopted the language of the neighboring Bantu-speaking populations,” says Tishkoff. “The groups may have split in different directions, with the Hadza and the Sandawe (Khoesan speakers from Tanzania) staying local and the San (Khoesan speakers from Botswana) moving south.” However, analysis of modern and ancient DNA indicates that there has been gene flow between the ancestors of the Hadza and Sandawe and the ancestors of the San, which could potentially explain some similarities in their language.

Newly understood human genetic diversity

The newly sequenced genomes identified 32 million SNPs, including more than 5 million that had never before been cataloged.

“The 32 million SNPs that were analyzed have just shed a new light on the importance of extending genetic studies in regions that have been previously marginalized around the globe,” says study co-author Thomas B. Nyambo of Kampala International University in Tanzania. “This is the way forward in the elucidation of evolutionary trends and their implication in tailored diagnostics and therapeutics.”

When the research team cross-referenced the previously identified SNPs with those in a widely used database used for clinical studies, they discovered many of the variants found in the African individuals in the study had been classified as pathogenic.

“This does not mean African populations have more ‘pathogenic’ variants,” says Shaohua Fan, a lead study author who completed a postdoc at Penn and is now at China’s Fudan University. “Rather, it emphasizes a strong need to include ethnically diverse populations in human genetic studies, especially because rarity is one criteria for determining a variant’s pathogenicity in clinical studies.”

In other words, some of these variants may have been miscategorized as associated with disease only because they were so uncommon in other populations, such as Europeans, which dominate these clinical databases.

“Comprehensively assessing genetic variants has been used as a strategy to study human disease and provides tremendous power to identify new loci associated with disease susceptibility and progression,” says Sununguko Wata Mpoloka of the University of Botswana. “Including understudied indigenous populations like those from Botswana in such studies will contribute tremendously to an understanding of precision medicine and could lead to tailormade drugs specific to such populations.”

Some of these variants may indeed play a meaningful role in health and disease. To get at these associations, the researchers not only compared mutations to existing databases and published studies, but also looked to see whether the variations occurred in the coding regions for proteins or in regions that could regulate gene expression for biologically relevant pathways and processes. They also looked for versions of a mutation, known as alleles, that occur at significantly different frequencies in different populations. These differences may arise because the alleles play a role in local adaptation to diverse environments and are positively selected, presumably because they confer some advantage to the people who carry them.

Several notable variants emerged from these analyses. In the San population of southern Africa, for example, the team found high numbers of SNPs near the PDPK1 gene, which had been shown by other scientists to play a role in pigmentation in mice. “Based on prior studies in our lab, we know that the San have relatively light skin color compared with other African populations,” says Yuanqing Feng, a postdoctoral researcher in the Tishkoff lab and a study co-author. “Thus, we hypothesized that SNPs near PDPK1 may affect pigmentation in humans.”

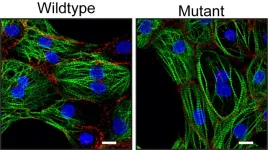

To generate mechanistic evidence for that hypothesis, the researchers tested the effect of one of these SNPs—shown to be common in the San—in skin cells grown in a petri dish. They found that inhibiting the region containing the variant altered expression levels of PDPK1 and reduced the levels of the skin pigment melanin in the lab-grown skin cells.

Other connections with health and function emerged from the study. The team’s analysis found a large number of variants near genes associated with bone growth in the Central African hunter-gatherers. These groups are known for their short stature, which is believed to be advantageous for the thick rainforest environment where they live. In pastoralist populations from East Africa, the team discovered enrichment for variants near genes that play a role in kidney development and function, possibly an adaptation to living in arid conditions. And in the Hadza hunter-gatherers in East Africa, they found a unique enrichment of variants near genes that play a role in heart development.

“My lab is now following up with some of these genes to see whether we can learn about the genetics of heart muscle development,” says Tishkoff. “If we understand how these genes are regulated, that could give us a clue as to why some people have a tendency toward cardiovascular disease. To understand abnormal function, you first have to understand normal function, and we speculate that there’s something about these individuals’ lifestyles—having to walk incredibly long distances, for example—that might make it advantageous to have certain changes in how the heart develops and functions.”

In addition, the researchers found gene variants related to blood pressure control in people with Nilo-Congo ancestry, West African groups that share ancestry with people from whom most African Americans are descended. “There’s a high incidence of hypertension and diabetes in people of African ancestry in the United States, and that’s largely due to socioeconomic factors,” Tishkoff says. “But there could be some genetic risk factors that, together with the environment in which they live, influence their risk for disease. Some of these could be adaptive in an African environment but maladaptive in a U.S. environment.”

These new datapoints may one day help inform precision medicine approaches that rely on understanding how genetics and other individual differences affect people’s disease risk, response to drugs, and more.

“There’s a huge amount of genomic variation in Africa that has not yet been well characterized,” Tishkoff adds. “We want to make sure all populations benefit from the genomics revolution, and we want to promote health equity, and therefore we need to include more diverse populations in these studies.”

Sarah Tishkoff is the David and Lyn Silfen University Professor in Genetics and Biology and a Penn Integrates Knowledge University Professor with appointments in the Perelman School of Medicine’s Department of Genetics and Department of Medicine and the School of Arts & Sciences’ Department of Biology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Shaohua Fan is a professor at China’s Fudan University and completed a postdoctoral fellowship in the Tishkoff lab at Penn.

Yuanqing Feng is a postdoctoral researcher in the Tishkoff lab at Penn.

Alfred Njamnshi is a professor of neurology and neuroscience at Cameroon’s University of Yaoundé I.

Thomas B. Nyambo is a member of the Department of Medical Biochemistry at Kampala International University in Tanzania.

Sununguko Wata Mpoloka is an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Botswana.

In addition to Tishkoff, Fan, Feng, Njamnshi, Nyambo, and Mpoloka, the study authors were: Penn Medicine’s Matthew E. B. Hansen, Marcia Beltrame, Alessia Ranciaro, Jibril Hirbo, and William Beggs; Stanford University’s Jeffrey P. Spence; University of Michigan’s Jonathan Terhorst; University of California, Berkeley’s Neil Thomas and Yun Song; Kampala International University’s Thomas Nyambo; University of Botswana’s Gaonyadiwe George Mokone; University of Yaoundé I’s Charles Folkunang; and Addis Ababa University’s Dawit Wolde Meskell and Gurja Belay.

Fan and Spence were co-first authors and Tishkoff was senior and corresponding author.

The study was supported primarily by the National Institutes of Health (grants GM134957, AR076241, and GM134922), the American Diabetes Association (Grant 1-19-VS-02), and the Penn Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-based Center (funded by NIH Grant AR069589 and the Perelman School of Medicine).

END

Genomic study of indigenous Africans paints complex picture of human origins and local adaptation

An international team of researchers led by Penn geneticists sequenced the genomes of 180 indigenous Africans. The results shed light on the origin of modern humans, African population history, and local adaptation.

2023-03-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Energy: More than two million citizens power Europe’s renewable energy transition

2023-03-02

More than two million citizens across 30 European countries have been involved in thousands of projects and initiatives as part of efforts to transition to renewable energy, according to an analysis published in Scientific Reports. With investments ranging between 6.2 and 11.3 billion Euros, these findings highlight the important role of collective action in the decarbonisation of Europe.

The energy system in Europe is undergoing a significant transition towards renewables and decarbonisation. However, the contribution ...

Performance of outpatient surgical procedures before, after onset of pandemic

2023-03-02

About The Study: The findings of this study suggest that despite calls for the expansion of outpatient surgery to mitigate the growing backlog of surgical cases in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, uptake of this practice occurred in only a small subset of operations. Further studies should explore potential barriers to the uptake of this approach, particularly for procedures that have been shown to be safe when performed in an outpatient setting.

Authors: Cornelius A. Thiels, D.O., M.B.A., of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, is the corresponding author

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1198)

Editor’s ...

Trends, variation in the use of active surveillance for management of low-risk prostate cancer

2023-03-02

About The Study: The results of this study of more than 20,000 men with low-risk prostate cancer suggest that active surveillance rates are rising nationally but are still suboptimal, and wide variation persists across practices and practitioners. Continued progress on this critical quality indicator is essential to minimize overtreatment of low-risk prostate cancer and by extension to improve the benefit-to-harm ratio of national prostate cancer early detection efforts.

Authors: Matthew R. Cooperberg, M.D., M.P.H., of the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center in San Francisco, is the corresponding ...

New mutation in the desmoplakin gene leads to ACM

2023-03-02

Researchers from the group of Eva van Rooij in collaboration with the UMC Utrecht identified a new mutation that leads to the cardiac disease arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM). They assessed the effect of this mutation on heart muscle cells and obtained new insights into the underlying mechanism that causes the disease. The results of this study, published on March 2nd in Stem Cell Reports, could contribute to the development of new treatments for ACM.

Desmosomes

Millions of heart muscle cells contract to let the heart fulfill ...

PCORI launches pioneering initiative offering up to $50 million to boost uptake of practice-changing health research findings in real-world settings

2023-03-02

WASHINGTON, DC – The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) today kicked off a multiyear initiative with an initial investment of $50 million to advance the uptake of practice-changing comparative clinical effectiveness research results into health care practice with the selection of 42 U.S. health systems to participate in its groundbreaking Health Systems Implementation Initiative (HSII). In addition, PCORI initiated the first in two stages of HSII funding, focusing on initial capacity-building efforts.

The array of participating health systems representing a wide range of care settings and populations will develop and implement ...

Robot provides unprecedented views below Antarctic ice shelf

2023-03-02

High in a narrow, seawater-filled crevasse in the base of Antarctica’s largest ice shelf, cameras on the remotely operated Icefin underwater vehicle relayed a sudden change in scenery.

Walls of smooth, cloudy meteoric ice suddenly turned green and rougher in texture, transitioning to salty marine ice.

Nearly 1,900 feet above, near where the surface of the Ross Ice Shelf meets Kamb Ice Stream, a U.S.-New Zealand research team recognized the shift as evidence of “ice pumping” – a process never before directly observed in an ice shelf crevasse, important to its stability.

“We were looking at ice that ...

New MIT Sloan research finds Americans are more receptive to counter-partisan messages than previously thought

2023-03-02

Party loyalty and partisan motivation may interfere less with Americans’ thinking than previously believed, MIT behavioral researchers Ben M. Tappin, Adam J. Berinsky, and David G. Rand report in new research published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

The study, which looked at how Democrats and Republicans react to persuasive messaging that doesn't align with their party leader’s position, challenges the view that party loyalty distorts how Americans process evidence and arguments.

“Our results are clear and unequivocal: Learning the in-party leader’s ...

Wisconsin cave holds tantalizing clues to ancient climate changes, future shifts

2023-03-02

Even in their dark isolation from the atmosphere above, caves can hold a rich archive of local climate conditions and how they've shifted over the eons. Formed over tens of thousands of years, speleothems — rock formations unique to caves better known as stalagmites and stalactites — hold secrets to the ancient environments from which they formed.

A newly published study of a stalagmite found in a cave in southern Wisconsin reveals previously undetected history of the local climate going back thousands of years. The new findings provide strong ...

Getting drugs across the blood-brain barrier using nanoparticles

2023-03-02

• The blood-brain barrier prevents most drugs from reaching brain tumors.

• A new method using nanoparticles transported drugs across this barrier in mice.

• The nanoparticles target a protein on tumor blood vessel cells called P-selectin.

• The nanoparticles improved the treatment in a model of aggressive pediatric brain cancer

Brain tumors are notoriously hard to treat. One reason is the challenge posed by the blood-brain barrier, a network of blood vessels and tissue with closely spaced cells. The barrier forms a tight seal to protect ...

Insights into the evolution of the sense of fairness

2023-03-02

Göttingen, March 2, 2023. A sense of fairness has long been considered purely human – but animals also react with frustration when they are treated unequally by a person. For instance, a well-known video shows monkeys throwing the offered cucumber at their trainer when a conspecific receives sweet grapes as a reward for the same task. Meanwhile, researchers have observed similarly frustrated reactions to unfair rewards in wolves, rats and crows. However, researchers still debate the reasons for this behavior: Does the frustration really stem from a dislike of unequal treatment, or is there another explanation? In a study with long-tailed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Why ‘being squeezed’ helps breast cancer cells to thrive

Mpox immune test validated during Rwandan outbreak

Scientists pinpoint protein shapes that track Alzheimer’s progression

Researchers achieve efficient bicarbonate-mediated integrated capture and electrolysis of carbon dioxide

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

Seeking abortion care across state lines after the Dobbs decision

Smartphone use during school hours and association with cognitive control in youths ages 11 to 18

[Press-News.org] Genomic study of indigenous Africans paints complex picture of human origins and local adaptationAn international team of researchers led by Penn geneticists sequenced the genomes of 180 indigenous Africans. The results shed light on the origin of modern humans, African population history, and local adaptation.