(Press-News.org) Yersinia bacteria cause a variety of human and animal diseases, the most notorious being the plague, caused by Yersinia pestis. A relative, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, causes gastrointestinal illness and is less deadly but naturally infects both mice and humans, making it a useful model for studying its interactions with the immune system.

These two pathogens, as well as a third close cousin, Y. enterocolitica, which affects swine and can cause food-borne illness if people consume infected meat, have many traits in common, particularly their knack for interfering with the immune system’s ability to respond to infection.

The plague pathogen is blood-borne and transmitted by infected fleas. Infection with the other two depends on ingestion. Yet the focus of much of the work in the field had been on interactions of Yersinia with lymphoid tissues, rather than the intestine. A new study of Y. pseudotuberculosis led by a team from Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine and published in Nature Microbiology demonstrates that, in response to infection, the host immune system forms small, walled-off lesions in the intestines called granulomas. It’s the first time these organized collections of immune cells have been found in the intestines in response to Yersinia infections.

The team went on to show that monocytes, a type of immune cell, sustain these granulomas. Without them, the granulomas deteriorated, allowing the mice to be overtaken by Yersinia.

“Our data reveal a previously unappreciated site where Yersinia can colonize and the immune system is engaged,” says Igor Brodsky, senior author on the work and a professor and chair of pathobiology at Penn Vet. “These granulomas form in order to control the bacterial infection in the intestines. And we show that if they don’t form or fail to be maintained, the bacteria are able to overcome the control of the immune system and cause greater systemic infection.”

The findings have implications for developing new therapies that leverage the host immune system, Brodsky says. A drug that harnessed the power of immune cells to not only keep Yersinia in check but to overcome its defenses, they say, could potentially eliminate the pathogen altogether.

A novel battlefield

Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica share a keen ability to evade immune detection.

“In all three Yersinia infections, a hallmark is that they colonize lymphoid tissues and are able to escape immune control and replicate, cause disease, and spread,” Brodsky says.

Earlier studies had shown that Yersinia prompted the formation of granulomas in the lymph nodes and spleen but had never observed them in the intestines until Daniel Sorobetea, a research fellow in Brodsky’s group, took a closer look at the intestines of mice infected with Y. pseudotuberculosis.

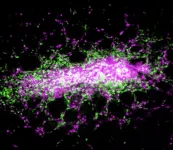

“Because it’s an orally acquired pathogen, we were interested in how the bacteria behaved in the intestines,” Brodsky says. “Daniel made this initial observation that, following Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection, there were macroscopically visible lesions all along the length of the gut that had never been described before.”

The research team, including Sorobetea and later Rina Matsuda, a doctoral student in the lab, saw that these same lesions were present when mice were infected with Y. enterocolitica, forming within five days after an infection.

A biopsy of the intestinal tissues confirmed that the lesions were a type of granuloma, known as a pyogranuloma, composed of a variety of immune cells, including monocytes and neutrophils, another type of white blood cell that is part of the body's front line in fighting bacteria and viruses.

Granulomas form in other diseases that involve chronic infection, including tuberculosis, for which Y. pseudotuberculosis is named. Somewhat paradoxically, these granulomas—while key in controlling infection by walling off the infectious agent—also sustain a population of the pathogen within those walls.

The team wanted to understand how these granulomas were both formed and maintained, working with mice lacking monocytes as well as animals treated with an antibody that depletes monocytes. In the animals lacking monocytes “these granulomas, with their distinct architecture, wouldn’t form,” Brodsky says.

Instead, a more disorganized and necrotic abscess developed, neutrophils failed to be activated, and the mice were less able to control the invading bacteria. These animals experienced higher levels of bacteria in their intestines and succumbed to their infections.

Groundwork for the future

The researchers believe the monocytes are responsible for recruiting neutrophils to the site of infection and thus launching the formation of the granuloma, helping to control the bacteria. This leading role for monocytes may exist beyond the intestines, the researchers believe.

“We hypothesize that it’s a general role for the monocytes in other tissues as well,” Brodsky says.

But the discoveries also point to the intestines as a key site of engagement between the immune system and Yersinia.

“Previous to this study we knew of Peyer’s patches to be the primary site where the body interacts with the outside environment through the mucosal tissue of the intestines,” says Brodsky. Peyer’s patches are small areas of lymphoid tissue present in the intestines that serve to regulate the microbiome and fend off infection.

In future work, Brodsky and colleagues hope to continue to piece together the mechanism by which monocytes and neutrophils contain the bacteria, an effort they’re pursing in collaboration with Sunny Shin’s lab in the Perelman School of Medicine’s microbiology department.

A deeper understanding of the molecular pathways that regulate this immune response could one day offer inroads into host-directed immune therapies, by which a drug could tip the scales in favor of the host immune system, unleashing its might to fully eradicate the bacteria rather than simply corralling them in granulomas.

“These therapies have caused an explosion of excitement in the cancer field,” Brodsky says, “the idea of reinvigorating the immune system. Conceptually we can also think about how to coax the immune system to be reinvigorated to attack pathogens in these settings of chronic infection as well.”

Igor E. Brodsky is the Robert R. Marshak Professor and chair of the Department of Pathobiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

Rina Matsuda is a doctoral student in the Brodsky Laboratory at Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine.

Daniel Sorobetea is a research fellow in the Brodsky Laboratory at Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine.

Brodsky, Matsuda, and Sorobetea coauthored the study with Penn Vet’s Stefan T. Peterson, James P. Grayczyk, Indira Rao, Elise Krespan, Matthew Lanza, Charles-Antoine Assenmacher, Daniel P. Beiting, and Enrico Radaelli and University Hospital Regensburg’s Matthias Mack. Brodsky is senior author, and Matsuda and Sorobetea were co-first authors.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants AI128530, AI1139102A1, DK123528, AI160741-01, AI141393-2, and AI164655), Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Foundation Blanceflor Postdoctoral Scholarship, Swedish Society for Medical Research, Sweden-America Foundation J. Sigfrid Edström Award, Mark Foundation, and National Science Foundation GRFP Award.

END

The immune system does battle in the intestines to keep bacteria in check

New research from the University of Pennsylvania demonstrates that Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, a relative of the bacterial pathogen that causes plague, triggers the body’s immune system to form lesions in the intestines called granulomas.

2023-03-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Switching to hydrogen fuel could prolong the methane problem

2023-03-13

Hydrogen’s potential as a clean fuel could be limited by a chemical reaction in the lower atmosphere, according to research from Princeton University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association.

This is because hydrogen gas easily reacts in the atmosphere with the same molecule primarily responsible for breaking down methane, a potent greenhouse gas. If hydrogen emissions exceed a certain threshold, that shared reaction will likely lead to methane accumulating in the atmosphere — with decades-long climate consequences.

“Hydrogen is theoretically the fuel of the future,” said Matteo Bertagni, a postdoctoral researcher at the High ...

Normalizing tumor blood vessels may improve immunotherapy against brain cancer

2023-03-13

BOSTON – A type of immune therapy called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of multiple types of blood cancers but has shown limited efficacy against glioblastoma—the deadliest type of primary brain cancer—and other solid tumors.

New research led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer March 10, 2023, suggests that drugs that correct abnormalities in a solid tumor’s blood vessels can improve the delivery and function of CAR-T cell therapy.

With CAR-T cell therapy, immune cells are taken from a ...

Wayne State researchers develop new technology to easily detect active TB

2023-03-13

DETROIT – A team of faculty from Wayne State University has discovered new technology that will quickly and easily detect active Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) infection antibodies. Their work, “Discovery of Novel Transketolase Epitopes and the Development of IgG-Based Tuberculosis Serodiagnostics,” was published in a recent edition of Microbiology Spectrum, a journal published by the American Society for Microbiology. The team is led by Lobelia Samavati, M.D., professor in the Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics in the School of Medicine. ...

Mahoney Life Sciences Prize awarded to UMass Amherst biologist Lynn Adler

2023-03-13

AMHERST, Mass. – University of Massachusetts Amherst biologist Lynn Adler has won the Mahoney Life Sciences Prize for her research demonstrating that different kinds of wildflowers can have markedly different effects on the health and reproduction rate of bumblebees.

“My lab studies the role that flowers play in pollinator health and disease transmission,” says Adler. “Flowers are of course a food source for pollinators, but, in some cases, nectar or pollen from specific plants can be medicinal. However, flowers are also high-traffic areas, and just like with humans, high-traffic areas can be hotspots for disease transmission. We’re tracing how different populations ...

Research highlights gender bias persistence over centuries

2023-03-13

New research from Washington University in St. Louis provides evidence that modern gender norms and biases in Europe have deep historical roots dating back to the Middle Ages and beyond, suggesting that DNA is not the only thing we inherit from our ancestors.

The findings — published on March 13, 2023 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) — highlight why gender norms have remained stubbornly persistent in many parts of the world despite significant strides made by the international ...

Swan populations grow 30 times faster in nature reserves

2023-03-13

Populations of whooper swans grow 30 times faster inside nature reserves, new research shows.

Whooper swans commonly spend their winters in the UK and summers in Iceland.

In the new study, researchers examined 30 years of data on swans at 22 UK sites – three of which are nature reserves managed by the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT).

Survival rates were significantly higher at nature reserves, and population growth was so strong that many swans moved to non-protected sites.

Based on these findings, the research team – led by the universities of Exeter and Helsinki – project that nature reserves could help double the number ...

FSU researchers find decaying biomass in Arctic rivers fuels more carbon export than previously thought

2023-03-13

The cycling of carbon through the environment is an essential part of life on the planet.

Understanding the various sources and reservoirs of carbon is a major focus of Earth science research. Plants and animals use the element for cellular growth. It can be stored in rocks and minerals or in the ocean. Carbon in the form of carbon dioxide can move into the atmosphere, where it contributes to a warming planet.

A new study led by Florida State University researchers found that plants and small organisms in Arctic rivers could be responsible for more than half the particulate organic matter flowing to the Arctic Ocean. That’s a significantly ...

Statins may reduce heart disease in people with sleep apnea

2023-03-13

NEW YORK, NY (March 13, 2023)--A new study by Columbia University researchers suggests that cholesterol-lowering drugs called statins have the potential to reduce heart disease in people with obstructive sleep apnea regardless of the use of CPAP machines during the night.

CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) therapy improves sleep quality and reduces daytime fatigue in people with obstructive sleep apnea. But based on findings from several recent clinical trials, CPAP does not improve heart health as physicians originally hoped.

Alternative ...

New process could capture carbon dioxide equivalent to forest the size of Germany

2023-03-13

New research suggests that around 0.5% of global carbon emissions could be captured during the normal crushing process of rocks commonly used in construction, by crushing them in CO2 gas.

The paper ‘Mechanochemical processing of silicate rocks to trap CO2’ published in Nature Sustainability says that almost no additional energy would be required to trap the CO2. 0.5% of global emissions would be the equivalent to planting a forest of mature trees the size of Germany.

The materials and construction industry ...

City or country living? Research reveals psychological differences

2023-03-13

Living in the country, in rural areas, has long been idealized as a pristine place to raise a family. After all, open air and room to run free pose distinct advantages. But new findings from a University of Houston psychology study indicate that Americans who live in more rural areas tend to be more anxious and depressed, as well as less open-minded and more neurotic. The study also revealed those living in the country were not more satisfied with their lives nor did they have more purpose, or meaning in life, than people who lived in urban areas.

The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] The immune system does battle in the intestines to keep bacteria in checkNew research from the University of Pennsylvania demonstrates that Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, a relative of the bacterial pathogen that causes plague, triggers the body’s immune system to form lesions in the intestines called granulomas.