(Press-News.org) Key findings:

There are no vaccines or therapies available for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection. This pathogen spreads easily and is extremely common in people worldwide.

Infection with LCMV can cause birth defects in developing fetuses, and severe illness and even death in the immuncompromised.

New findings from La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) scientists show how an engineered antibody can target LCMV and neutralize the virus. They found this antibody has the potential to both prevent infection and treat an already established infection.

With this better understanding of LCMV's weak spots, scientists can move forward with broadly protective vaccine strategies.

LA JOLLA, CA—An old virus, and a beacon for exploring the immune system.

Since the 1930s, scientists have explored a virus called LCMV (short for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus) to reveal the hidden workings of the immune system. The virus is carried by rodents, which makes it a useful tool for laboratory research in mice. By investigating how the mouse immune system fights LCMV, researchers can catch immune cells and antibodies in action.

Early LCMV studies in mice led to the first-ever glimpses of how immune cells recognize invaders and how T cells remember past infections. The 1996 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to scientists who used LCMV to reveal exactly how immune cells tell pathogens apart from the body's own cells.

"LCMV has been utilized for nearly a century now as a kind of beacon for understanding how the host immune response deals with viral infection," says Alex Moon-Walker, Ph.D., a former LJI postdoctoral researcher who now works as a researcher in the biomedical industry.

Yet in all this time, scientists haven't had a clear look at the viral machinery LCMV uses to infect host cells. Solving the structure of this piece of machinery—called LCMV's glycoprotein—is important for developing vaccines or future therapies against the virus.

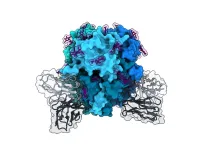

Now a new LJI study, published in Cell Chemical Biology, gives scientists the first-ever view of the pre-fusion LCMV glycoprotein trimer. This 3D structure shows precisely where the viral machinery may be vulnerable to antibody attack. What’s more, the new study is the first to show that an engineered antibody can prevent the disease caused by the virus, opening up a route to a needed medical treatment.

LCMV is also a human pathogen, spread by the mice that inhabit our homes and cities. People can get very sick from LCMV infections, especially people with compromised immune systems, such as people receiving organ transplants. The virus can also cross the placenta and infect a developing fetus, leading to serious birth defects or even fetal death.

"Even though LCMV has been characterized primarily as a mouse pathogen, the virus has unfortunately been neglected as a human pathogen as well," says LJI Instructor Kathryn Hastie, Ph.D., who also serves as Director of the LJI Antibody Discovery Center. "So there's no vaccine or therapeutic treatment for LCMV."

“The immune system is great at making antibodies, but your immune cells can't do their jobs unless they can see the right target on a pathogen. To prevent or treat LCMV infection, we need to know where the virus may be vulnerable to antibody attack,” says LJI Professor Shane Crotty, Ph.D., who co-led the study with LJI President and CEO Erica Ollmann Saphire, Ph.D., Hastie, and Moon-Walker.

Catching LCMV in action

A high-resolution look at LCMV's glycoprotein structure is an important step toward discovering where the virus is vulnerable. This structure has proven hard to capture because of its propensity to unfold. The viral structure is literally a moving target. Once the virus is inside a rodent or a human, the virus makes a beeline for a host cell. After attaching, LCMV is taken inside host cells where it is sent to compartments that are acidic. The acidic environment inside the compartments changes the shape, or conformation, of the LCMV glycoprotein, and this conformational change promotes fusion between the viral and host cell membrane, a key step in the virus’ infection cycle. Antibodies can only fight the virus if they can catch the glycoprotein in its pre-fusion stage.

"If you can prevent the glycoprotein from undergoing this conformational change, then you essentially can neutralize the pathogen and stop it from infecting cells in the first place," says Moon-Walker.

For the new study, Moon-Walker and Hastie engineered a version of the glycoprotein in its "prefusion state." Their work built on Hastie's experience with another dangerous pathogen: Lassa virus.

A window into LCMV

Lassa virus and LCMV both belong to the Arenaviridae family. Lassa also infects rodents, but it is much more likely than LCMV to cause serious symptoms, even death, in human hosts. In 2017, Hastie solved the structure of the Lassa glycoprotein in its pre-fusion stage. Her work in the Saphire Lab showed how to stabilize a tricky glycoprotein and served as a template for the new LCMV research.

Once they had a stable version of the LCMV glycoprotein, the researchers introduced it to an antibody called M28. The researchers had engineered M28 from an antibody found in the blood of a Lassa virus survivor. Because they are related, Lassa and LCMV were similar enough that M28 could target and bind to LCMV as well.

The scientists then used a high-resolution imaging technique called cryo-electron microscopy to capture the 3D structure of the LCMV glycoprotein together ("in complex") with antibody M28. The new structure reveals the details of the three-side glycoprotein "trimer" at a nearly atomic level.

The researchers could also see how M28 blocks infection by "locking" the LCMV glycoprotein into its pre-fusion state. This was a huge advance. As Hastie explains, scientists have never found a class of neutralizing antibodies against LCMV in mice or humans. Thanks to M28, the LJI team had the first look at where a neutralizing antibody in a LCMV therapy could attack. The next step was for the Crotty Lab to see if the antibody could prevent or treat the disease.

A step toward LCMV therapies

In experiments with mice, the researchers found that M28 works as a therapy against LCMV. The engineered antibody can be given before viral exposure to block infection or after exposure to treat an infection.

"This is the first time anybody has demonstrated the protective activity of a human antibody against LCMV," says Hastie. She imagines a similar therapy might someday be given to organ transplant patients before a procedure or to pregnant people after a known LCMV exposure.

Going forward, the researchers are interested in continuing the hunt for more antibodies that could neutralize LCMV. They say it's possible scientists could one day find antibodies that cross-neutralize different types of arenaviruses, opening the door to a "pan-arenavirus" vaccine against Lassa virus, LCMV, and other pathogens.

Saphire is confident the collaborative effort will succeed. “Combining forces and combining tools revealed the target, designed the therapy, and proved it would work,” she explains. “The team built from one virus’s insights to another to create something more broadly protective for human health.”

Additional authors of the study, "Structural basis for antibody-mediated neutralization of Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus," include Zeli Zhang, Dawid S. Zyla, Tierra K. Buck, Haoyang Li, Ruben Diaz Avalos, and Sharon L. Schendel.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; grants U19 AI142790, R01 AI132244, R01 AI14125, P01 AI145815, R21 AI137809, F31 AI154700) the NIH's National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; T32 training grant AI125179) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (fellowships P2EZP3_195680 and P500PB_210992)

END

We've learned a lot from lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus—now the time has come to fight it

LJI scientists share high-resolution view of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) glycoprotein together with a neutralizing antibody

2023-03-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

RSV hospitalizations spiked unusually high in late 2021, study finds

2023-03-28

The COVID-19 pandemic posed an immense challenge on the health care industry in 2020 and 2021. While hospitals were inundated with COVID-19 cases, other illnesses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) saw a decrease in hospital visits, particularly in the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021.

A Texas A&M University School of Public Health study recently published in the journal Frontiers found that while there were an unusually low number of hospitalizations in 2020, there was an unusual peak in the third quarter of 2021, when hospital admissions for RSV were approximately twice ...

Tiny yet hazardous: New study shows aerosols produced by contaminated bubble bursting are far smaller than predicted

2023-03-28

A cold sparkling water.

Waves crashing on the beach.

The crackle of a bonfire.

Steam from a kettle.

These are not only the makings of a relaxing weekend, but also sources of aerosols in our environment. Though some of these sources of aerosols aren’t much of a concern, aerosols originating from industrial sources, such as wastewater treatment plants, and even natural sources, such as sea spray and dust, have the capacity to make more of an impact on the environment and even public health.

An aerosol ...

Journal advances study of Alzheimer’s caregiving across diverse contexts

2023-03-28

A new supplemental issue to The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences features papers resulting from a gathering of experts that emphasized racial/ethnic and contextual factors in the study of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) care using a team science approach.

According to this journal issue, titled “ADRD Care in Context,” recent estimates indicate that 6.5 million people in the U.S. live with ADRD, and more than 11 million Americans care for people with these conditions, providing 16 billion hours (valued at $271 billion) of unpaid assistance annually. Further, older adults from minoritized ...

Brightest gamma-ray burst ever observed reveals new mysteries of cosmic explosions

2023-03-28

Cambridge, Mass. – On October 9, 2022, an intense pulse of gamma-ray radiation swept through our solar system, overwhelming gamma-ray detectors on numerous orbiting satellites, and sending astronomers on a chase to study the event using the most powerful telescopes in the world.

The new source, dubbed GRB 221009A for its discovery date, turned out to be the brightest gamma-ray burst (GRB) ever recorded.

In a new study that appears today in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, observations of GRB 221009A spanning from radio ...

Chinese space telescopes accurately measure brightest gamma-ray burst ever detected

2023-03-28

At 2AM of March 29, 2023 (Beijing Time), the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), together with some 40 research institutions worldwide, released their latest discoveries on the brightest Gamma-Ray Burst (dubbed as GRB 221009A) ever detected by human.

With the unique observations made by two Chinese space telescopes, namely Insight-HXMT and GECAM-C, scientists were able to accurately measure how bright and how much energy released by this burst, which is the key to understand this historical event.

For ...

ORNL-led team designs molecule to disrupt SARS-CoV-2 infection

2023-03-28

A team of scientists led by the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory designed a molecule that disrupts the infection mechanism of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and could be used to develop new treatments for COVID-19 and other viral diseases.

The molecule targets a lesser-studied enzyme in COVID-19 research, PLpro, that helps the coronavirus multiply and hampers the host body’s immune response. The molecule, called a covalent inhibitor, forms a strong chemical bond with its intended protein target and thus increases its effectiveness as an antiviral treatment.

“We’re ...

Researchers discover two subtypes of insulin-producing cells

2023-03-28

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (March 28, 2023) — A team led by Van Andel Institute and Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics scientists has identified two distinct subtypes of insulin-producing beta cells, or ß cells, each with crucial characteristics that may be leveraged to better understand and treat Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

ß cells are critical guardians of the body’s metabolic balance. They are the only cells capable of producing insulin, which regulates blood sugar levels by designating dietary sugar for immediate use ...

Extinction of steam locomotives derails assumptions about biological evolution

2023-03-28

LAWRENCE — When the Kinks’ Ray Davies penned the tune “Last of the Steam-Powered Trains,” the vanishing locomotives stood as nostalgic symbols of a simpler English life. But for a paleontologist at the University of Kansas, the replacement of steam-powered trains with diesel and electric engines, as well as cars and trucks, might be a model of how some species in the fossil record died out.

Bruce Lieberman, professor of ecology & evolutionary biology and senior curator of invertebrate paleontology at the KU Biodiversity Institute & Natural History Museum, sought to use steam-engine history to test the merits of “competitive exclusion,” ...

aOncotarget | Polyisoprenylated cysteinyl amide inhibitors deplete g-proteins in cancer cells

2023-03-28

“[...] mutations in G-proteins have been associated in the progress of several cancers [...]”

BUFFALO, NY- March 28, 2023 – A new research paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 14 on March 24, 2023, entitled, “Polyisoprenylated cysteinyl amide inhibitors deplete singly polyisoprenylated monomeric G-proteins in lung and breast cancer cell lines.”

Finding effective therapies against cancers driven by mutant and/or overexpressed hyperactive G-proteins remains an area of active research. Polyisoprenylated cysteinyl amide inhibitors (PCAIs) are agents that mimic the essential posttranslational ...

Molecular imaging offers insight into chemo-brain

2023-03-28

Reston, VA—A newly published literature review sheds light on how nuclear medicine brain imaging can help evaluate the biological changes that cause chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment (CRCI), commonly known as chemo-brain. Armed with this information, patients can understand better the changes in their cognitive status during and after treatment. This summary of findings was published ahead-of-print by The Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

CRCI describes a clinical condition characterized by memory and concentration impairment, difficulties with information processing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New study from Jeonbuk National University finds current climate pledges may miss Paris targets

Theoretical principles of band structure manipulation in strongly correlated insulators with spin and charge perturbations

A CNIC study shows that the heart can be protected during chemotherapy without reducing antitumor efficacy

Mayo Clinic study finds single dose of non-prescribed Adderall raises blood pressure and heart rate in healthy young adults

Engineered immune cells show promise against brain metastases in preclinical study

Improved EV battery technology will outmatch degradation from climate change

AI cancer tools risk “shortcut learning” rather than detecting true biology

Painless skin patch offers new way to monitor immune health

Children with poor oral health more often develop cardiovascular disease as adults

GLP-1 drugs associated with reduced need for emergency care for migraine

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

[Press-News.org] We've learned a lot from lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus—now the time has come to fight itLJI scientists share high-resolution view of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) glycoprotein together with a neutralizing antibody