(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — In the face of a warming climate that is having a profound effect on global biodiversity and will change the distribution and abundance of many animals, a Penn State-led research team has developed a statistical model that improves estimates of habitat suitability and extinction probability for cold-blooded animals as temperatures climb.

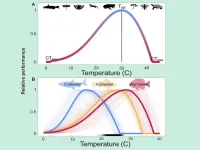

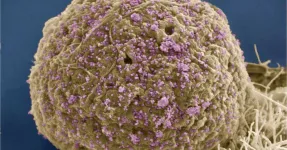

Cold-blooded animals — a diverse group including fish, reptiles, amphibians and insects — comprise most species on Earth. The body temperature of cold-blooded animals is strongly influenced by the temperature of their environment. Because their growth, reproductive success and survival is tightly coupled to environmental temperatures, climate change represents a significant threat to them.

Understanding the future effects of climate change on biodiversity is a global priority, according to research team leader Tyler Wagner, a scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey and a Penn State adjunct professor of fisheries ecology. But predicting where a species will exist and in what abundance under future temperatures is extremely challenging, he noted, because for many species this means estimating responses to temperatures that the animals have not yet experienced, and scientists have not yet observed.

To more precisely estimate the effects of climate change on cold-blooded animals, in a new study, the researchers developed a statistical method to fuse data collected in the field describing the distribution and abundance of many cold-blooded animals with laboratory-derived information about species-specific temperature performance and tolerance.

In findings published today (April 3) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Wagner and colleagues report the development of an innovative statistical modeling approach. Their newly developed model, which they call the “Physiologically Guided Abundance Model,” or PGA Model, can be applied across almost all cold-blooded animals, and is believed to have great potential to help inform the formation of climate adaptation and management strategies.

“The challenge was how to combine these two sources of information and use laboratory-derived information to help inform landscape-scale predictions under future climates not experienced by animals in their current ranges,” said Wagner, who is assistant unit leader of the Pennsylvania Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit in the College of Agricultural Sciences. “The model we created accomplishes that.”

The PGA model combines observations of species abundance and environmental conditions with laboratory-derived data on the physiological response of cold-blooded animals to temperature to predict species geographical distributions and abundance in response to a warming world. Without including species’ physiological preferences in a model, Wagner suggests, it is difficult to realistically forecast cold-blooded animals’ fate.

“When trying to predict, or extrapolate, the effects of climate change on animal distribution and abundance, scientists now often only use information that describes the relationships between abundance and distributions and temperature under current conditions,” he said. “These relationships are then used to extrapolate under future temperature conditions.”

However, this approach assumes that species-environment relationships are biologically meaningful under future temperatures and, importantly, fails to account for the tight link between environmental temperatures and cold-blooded animal physiology, Wagner explained.

“Although cold-blooded animals are understudied when it comes to understanding how their distributions and abundance will respond to climate change, these animals are relatively well-studied when it comes to laboratory-derived information about how changes in environmental temperatures affect physiology and performance,” he said. “In fact, most cold-blooded animals share a similar functional response in relative performance with increasing temperatures, which can be generalized across a diversity of taxa.”

The researchers developed their PGA model using data from three fish species that differ in their thermal preference and tolerance across more than 1,300 lakes located in the U.S. Midwest. They compared the PGA model’s results to those from a traditional model that does not incorporate species’ physiological responses. Fishes considered in the research were cisco (coldwater), yellow perch (coolwater) and bluegill (warmwater).

The researchers predicted species distributions and abundance at each lake under current conditions and for 1.8-, 3.6-, 5.4- and 7.2-degree (Fahrenheit) increases in mean July water temperatures. A 7.2-degree F increase corresponds to the predicted average regional increase in air temperature across the Midwest region for the 2071–2100 time period.

While the results of the traditional model did not predict that any of the fish species would be extirpated, or locally driven out, by climate change, the PGA model revealed that cold-adapted fish would be extirpated in 61% of their current habitat with rising temperature.

Gretchen Hansen, assistant professor at the University of Minnesota and a coauthor on the study, suggested that models that do not include physiological preferences may lead to underestimations of the risk climate change may pose to cold-adapted species.

“We showed that temperature-driven changes in distribution, local extinction, and abundance of cold-, cool- and warm-adapted species varied substantially when physiological information was incorporated into the model,” she said. “The PGA model provided more realistic predictions under future climate scenarios compared with traditional approaches and has great potential for more realistically estimating the effects of climate change on cold blooded species.”

Also contributing to the research at Penn State was Christopher Custer, doctoral degree student in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Management; as well as Erin Schliep, Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University; Joshua North, Climate and Ecosystem Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; and Holly Kundel and Jenna Ruzich, Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, University of Minnesota.

This research was funded by the U.S. Geological Survey Midwest Climate Adaptation Science Center and the National Science Foundation.

END

Innovative method predicts the effects of climate change on cold-blooded animals

Statistical model shows how warming may affect distribution, abundance of amphibians, reptiles, fish, insects

2023-04-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Gulf offshore oil and gas production has double the climate impact as inventories report

2023-04-03

Images

By directly measuring greenhouse gas emissions from an airplane flying over the Gulf of Mexico, a University of Michigan-led team found that the nation's largest offshore fossil fuel production basin has twice the climate warming impact as official estimates.

The work could have bearing on future energy production in the gulf, as decisions about expanding oil and gas harvesting depend on calculations of the climate impact.

While a gap between reported and measured methane emissions in the basin has been noted in the past, this study is believed ...

Squash bees flourish in response to agricultural intensification

2023-04-03

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — While pollinator populations of many species have plummeted worldwide, one bee species is blowing up the map with its rapid population expansion. The key to this insect’s success? Its passion for pumpkins, zucchinis, and other squashes, and the massive increase in cultivation of these crops across North America over the last 1,000 years.

A new study led by Penn State found that the squash bee (Eucera pruinosa) has evolved in response to intensifying agriculture — namely squashes in the genus ...

Strong ultralight material could aid energy storage, carbon capture

2023-04-03

HOUSTON – (April 3, 2023) – 2D materials get their strength from their atom-thin, sheetlike structure. However, stacking multiple layers of a 2D material will sap it of the qualities that make it so useful.

Rice University materials scientist Jun Lou and collaborators at the University of Maryland showed that fine-tuning interlayer interactions in a class of 2D polymers known as covalent organic frameworks (COFs) can determine the materials’ loss or retention of desirable ...

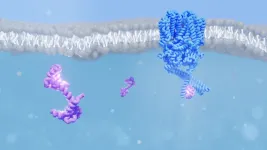

Calcium sensor helps us to see the stars

2023-04-03

Using cryo-electron microscopy and mass spectrometry, researchers from PSI have deciphered the structure of an ion channel found in the eye while it interacts with the protein calmodulin – a structure that has eluded scientists for three decades. They believe that this interaction could explain how our eyes can achieve such remarkable sensitivity to dim light. Their results are published in the journal PNAS.

As you look at the bright screen of your phone or computer, ion channels in your eyes close in response to the light. This is the final step of a biochemical ...

New research could spur broader use of 2D materials

2023-04-03

They’re considered some of the strongest materials on the planet, but tapping that strength has proved to be a challenge.

2D materials, thinner than the most delicate onionskin paper, have attracted intense interest because of their incredible mechanical properties. Those properties, however, dissipate when the materials are stacked in multiple layers, thus limiting their usefulness.

“Think of a graphite pencil,” says Teng Li, Keystone Professor at the University of Maryland’s (UMD) Department of Mechanical Engineering. “Its core is made of graphite, and graphite ...

April issues of American Psychiatric Association journals cover genetic underpinnings of common disorders, a digital intervention for depression and anxiety in youth, and more

2023-04-03

WASHINGTON, D.C., April 3, 2023 — The latest issues of three of the American Psychiatric Association’s journals, The American Journal of Psychiatry, Psychiatric Services, and The American Journal of Psychotherapy, are now available online.

The April issue of The American Journal of Psychiatry features genetic, neuroimaging, and behavioral neuroscience studies that focus on the underpinnings of mood disorders, psychotic disorders, autism, and stress-related disorders. Highlights from the issue:

Lower Availability of Mitochondrial Complex I in Anterior Cingulate Cortex in ...

Royal reception on Commonwealth Day 2023 for Sri Lankan PhD researcher

2023-04-03

A PhD researcher from the University of Huddersfield’s Global Disaster Resilience Centre (GDRC) was invited by His Majesty The King and The Queen Consort to attend a special reception at Buckingham Palace and more, in celebration of Commonwealth Day 2023.

Malith Senevirathne is a PhD student at the GDRC, within the University’s School of Applied Sciences and a Research Assistant for the CORE project (sCience and human factOr for Resilient sociEty), funded by the European Commission. As ...

Can investigators use household dust as a forensic tool?

2023-04-03

A North Carolina State University-led study found it is possible to retrieve forensically relevant information from human DNA in household dust. After sampling indoor dust from 13 households, the researchers were able to detect DNA from household residents over 90% of the time, and DNA from non-occupants 50% of the time. The work could be a way to help investigators find leads in difficult cases.

Specifically, the researchers were able to obtain single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, from the dust samples. SNPs are sites within the genome that vary between individuals – corresponding ...

Center for AIDS Research receives $15 million renewal grant from NIH

2023-04-03

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, has awarded a five-year, $15.45 million grant to the San Diego Center for AIDS Research (SD CFAR) at UC San Diego, renewing support that extends back to an original establishing grant in 1994 at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

"The grant renewal represents NIAID's continued and enduring investment in our mission to be a critical regional resource in HIV research and education, to advance the discovery and development of ...

Moderate exercise safe for people with muscle pain from statins

2023-04-03

Statin therapy does not exacerbate muscle injury, pain or fatigue in people engaging in moderate-intensity exercise, such as walking, according to a study published today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. The findings are reassuring for people who experience muscle pain or fatigue from statins but need to engage in physical activity to keep their cholesterol levels low and their hearts healthy.

Statins have long been the gold standard for lowering LDL or “bad” cholesterol ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

[Press-News.org] Innovative method predicts the effects of climate change on cold-blooded animalsStatistical model shows how warming may affect distribution, abundance of amphibians, reptiles, fish, insects