(Press-News.org) The story of how ancient wolves came to claim a place near the campfire as humanity’s best friend is a familiar tale (even if scientists are still working out some of the specifics). In order to be domesticated, a wild animal must be tamable — capable of living in close proximity to people without exhibiting dangerous aggression or debilitating fear. Taming was the necessary first step in animal domestication, and it is widely known that some animals are easier to tame than others.

But did humans also favor certain wild plants for domestication because they were more easily “tamed”? Research from Washington University in St. Louis calls for a reappraisal of the process of plant domestication, based on almost a decade of observations and experiments. The behavior of erect knotweed, a buckwheat relative, has WashU paleoethnobotanists completely reassessing our understanding of plant domestication.

“We have no equivalent term for tameness in plants,” said Natalie Mueller, assistant professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University. “But plants are capable of responding to people. They have a developmental capacity to be tamed.”

Her work with early indigenous North American crops shows that some wild plants respond quickly to clearing, fertilizing, weeding or thinning. Plants that respond in ways that make cultivation easier or more productive could be considered more easily tamed than those that cannot.

“If plants responded rapidly in ways that were beneficial to early cultivators — for example by producing higher yields, larger seeds, seeds that were easier to sprout, or a second crop in a single growing season — this would have encouraged humans to continue investing in the co-evolutionary relationship,” she said.

This capacity to express different traits and characteristics in response to the environment is called plasticity, and not all species are equally plastic.

“Some plants respond quickly and obviously to cultivation and care,” Mueller said. “I think ancient people would have noticed that they could double their yields just by thinning out dense stands of plants. This is one of the simplest and most common gardening techniques, but it has many important effects on the development of plants.”

What would an early farmer do?

Mueller’s study, published April 7 in PLOS ONE, focuses on work with a plant called erect knotweed, a member of the buckwheat family that was domesticated by indigenous farmers in eastern North America. The domesticated sub-species is now extinct; humans don’t eat it anymore. But Mueller and others have previously uncovered caches of seeds stored in caves, charred plant remnants in ancient hearths, and even the seeds of erect knotweed in human feces, clear evidence that this species was once consumed as a staple food.

Mueller, who studies lost crops, has spent years growing erect knotweed and other crop progenitors in experimental gardens, including at Washington University’s environmental field station, Tyson Research Center. She hasn’t always been successful with growing the plants she collects in the wild. In that way, Mueller can relate to the early farmers who similarly experimented with plants to discover their potential.

Her efforts have often been stymied by seed dormancy, a common feature among wild plants.

Unlike seeds you buy at the garden store, the seeds of most wild plants will not germinate if you simply sprinkle some water on them. Their requirements for germination are diverse and shaped by their evolutionary history. For example, if a plant has evolved in a place with a winter, like the Midwest, its seeds may not germinate unless they experience a long cold period. This prevents them from germinating too soon in the wild — they are waiting for spring. Domesticated plants have lost their diverse germination requirements.

The loss of germination inhibitors has presented a paradox to theorists of domestication. Many of the selective pressures that could have favored the evolution of this trait derive from planting seeds. But why would ancient people have started planting seeds if none of them germinated?

With erect knotweed, Mueller experienced a breakthrough of sorts. Based on four seasons of observations, Mueller determined that growing wild plants in the low-density conditions typical of a cultivated garden (i.e. spaced out and weeded) triggers plants to produce seeds that germinate more easily. This makes the harvests easier to plant successfully the next time around, eliminating a key barrier to further selection.

“Our results show that erect knotweed grown in low-density agroecosystems spontaneously ‘act domesticated’ in a single growing season, before any selection has occurred,” Mueller said.

Think of it as the plant equivalent to that first wolf who, though still a wild animal, sat down with its human friend around the fire. This is a behavioral shift, rather than an evolutionary one, but it allows new evolutionary pathways to open up.

A role for plant behavior

Mueller believes there is a bias in domestication studies toward viewing this changeability, or plasticity, as noise that is getting in the way of attempts to explain evolutionary change. Instead, this paper argues that we need to understand the development and behavior of wild crop relatives in order to explain the evolutionary process of domestication.

“Because we lack the practical experience with crop progenitors that ancient people had, these effects of the environment on plant development have gone mostly unnoticed and understudied,” Mueller said.

Her findings could have applications for developing new food crops: there is no reason why we have to be limited to the plants that our ancestors domesticated thousands of years ago.

Some researchers have been calling for de novo domestication — selecting wild plants with desirable characteristics and intentionally domesticating them. It may make sense to start looking to wild plants that are easily tamed as potential crops that could be developed for the future, Mueller said.

This paper also contributes to a growing awareness that plants are responsive and communicative beings. Though this idea is cutting-edge and hotly debated in biology and ecology, it is widespread in indigenous North American philosophies and probably would have been held by the people who domesticated erect knotweed and other plants thousands of years ago.

Recent research has shown how plants warn relatives about herbivores using chemical signaling, share resources through mycorrhizal networks and even emit noises when they are injured or stressed.

“You can’t explain plant domestication if you only consider the behaviors of humans, because domestication is the result of reciprocal relationships between multiple species that are all capable of responding to each other,” Mueller said.

END

Early crop plants were more easily ‘tamed’

2023-04-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Table tennis brain teaser: Playing against robots makes our brains work harder

2023-04-10

Captain of her high school tennis team and a four-year veteran of varsity tennis in college, Amanda Studnicki had been training for this moment for years.

All she had to do now was think small. Like ping pong small.

For weeks, Studnicki, a graduate student at the University of Florida, served and rallied against dozens of players on a table tennis court. Her opponents sported a science-fiction visage, a cap of electrodes streaming off their heads into a backpack as they played against either Studnicki or a ball-serving machine. That cyborg look was vital ...

For chatbots and beyond: Improving lives with data starts with improving machine learning

2023-04-10

You’d be hard pressed to find an industry today that doesn’t use data in some capacity. Whether it's health care workers using data to report the rate of flu infections in a certain state, manufacturers using data to better understand average production times, or even a small coffee shop owner flipping through sales data to learn about the previous month’s bestselling latte, data can reveal patterns and offer insights into our everyday behavior.

All of this data plays a critical role in artificial intelligence ...

Mild COVID during pregnancy does not slow brain development in babies, study finds

2023-04-10

NEW YORK, NY (April 10, 2023)--Columbia researchers have found that babies born to moms who had mild or asymptomatic COVID during pregnancy are normal, based on results from a comprehensive assessment of brain development.

The findings expand on a smaller study that used maternal reports to assess the development of babies born in New York City during the first wave of the pandemic. That study found no differences in brain development between babies who were exposed to COVID in utero and those who were not exposed.

For the new study, the researchers developed a method of observing infants remotely, ...

Kids judge Alexa smarter than Roomba, but say both deserve kindness

2023-04-10

DURHAM, N.C. –- Most kids know it’s wrong to yell or hit someone, even if they don’t always keep their hands to themselves. But what about if that someone’s name is Alexa?

A new study from Duke developmental psychologists asked kids just that, as well as how smart and sensitive they thought the smart speaker Alexa was compared to its floor-dwelling cousin Roomba, an autonomous vacuum.

Four- to eleven-year-olds judged Alexa to have more human-like thoughts and emotions than Roomba. But despite the perceived difference in intelligence, kids felt neither the Roomba nor the Alexa deserve to be yelled at or harmed. That feeling dwindled as kids advanced ...

Hooper creating public database of slaving voyages across the Indian Ocean and Asia

2023-04-10

Jane Hooper, Associate Professor, History, received funding for the project: "Global Passages: Creating a Public Database of Slaving Voyages across the Indian Ocean and Asia."

Hooper, along with three other scholars, has received a three-year digital production grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support a major expansion of the open access SlaveVoyages website, available online at https://www.slavevoyages.org. The primary investigators will create an Indian Ocean and Asia (IOA) database of voyages that ...

A new technique opens the door to safer gene editing by reducing the mutation problem in gene therapy

2023-04-10

CRISPR-Cas9 is widely used to edit the genome by studying genes of interest and modifying disease-associated genes. However, this process is associated with side effects including unwanted mutations and toxicity. Therefore, a new technology that reduces these side effects is needed to improve its usefulness in industry and medicine. Now, researchers at Kyushu University in southern Japan and Nagoya University School of Medicine in central Japan have developed an optimized genome-editing method that vastly reduces mutations, opening the door to more effective treatment of genetic diseases with fewer unwanted mutations. Their findings were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Genome-editing ...

Medicaid ‘cliff’ adds to racial and ethnic disparities in care for near-poor seniors

2023-04-10

PITTSBURGH, April 10, 2023 – Black and Hispanic older adults whose annual income is slightly above the federal poverty level are more likely than their white peers to face cost-related barriers to accessing health care and filling medications for chronic conditions, according to new research led by a University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health scientist.

Published today in JAMA Internal Medicine, the analysis links these disparities to a Medicaid “cliff” – an abrupt end ...

Potential drug treats fatty liver disease in animal models, brings hope for first human treatment

2023-04-10

A recently developed amino acid compound successfully treats nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in non-human primates — bringing scientists one step closer to the first human treatment for the condition that is rapidly increasing around the world, a study suggests.

Researchers at Michigan Medicine developed DT-109, a glycine-based tripeptide, to treat the severe form of fatty liver disease called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. More commonly known as NASH, the disease causes scarring and inflammation in the liver and is estimated to affect up to 6.5% of the global population.

Results ...

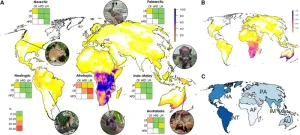

Scientists show how we can anticipate rather than react to extinction in mammals

2023-04-10

Most conservation efforts are reactive. Typically, a species must reach threatened status before action is taken to prevent extinction, such as establishing protected areas. A new study published in the journal Current Biology on April 10 shows that we can use existing conservation data to predict which currently unthreatened species could become threatened and take proactive action to prevent their decline before it is too late.

“Conservation funding is really limited,” says lead author Marcel Cardillo (@MarcelCardillo) of Australian National University. “Ideally, what we need is some way of anticipating species that may not be threatened ...

This elephant’s self-taught banana peeling offers glimpse of elephants’ broader abilities

2023-04-10

Elephants like to eat bananas, but they don’t usually peel them first in the way humans do. A new report in the journal Current Biology on April 10, however, shows that one very special Asian elephant named Pang Pha picked up banana peeling all on her own while living at the Berlin Zoo. She reserves it for yellow-brown bananas, first breaking the banana before shaking out and collecting the pulp, leaving the thick peel behind.

The female elephant most likely learned the unusual peeling behavior ...