(Press-News.org) A research team led by Seishiro Tada and Takanobu Tsuihiji of the University of Tokyo shows that the living warm-blooded descendants of theropod dinosaurs evolved a better nasal cooling system aided by larger nasal cavities than cold-blooded animals. The study provides clues to the evolution of nasal cooling in warm-blooded animals from their theropod dinosaur ancestors.

Endotherms, or warm-blooded animals, maintain their high body temperature through internal heat sources. Birds, humans, and other mammals are endotherms. But ectotherms, or cold-blooded animals such as reptiles, use external heat sources to keep warm. Humans seek air-conditioning or a cold drink on a hot summer day to cool off. How do other animals prevent overheating or frying their heat-sensitive brain? The answer might be in their nose.

In endotherms like birds, mammals, and you, the nose not only sniffs out scents and stenches but also aids in heat exchange thanks to the small undulating scroll-shaped structures called respiratory turbinates made of bone and cartilage tissue. They may help moisten the inhaled air, and exchange heat from the circulating blood, which can cool the brain.

A previous study showed that the size of the nasal cavity in ectotherms and endotherms correlates with body size. “But its physiological role has been controversial,” said Seishiro Tada, a graduate student at the University of Tokyo. Does a large nasal cavity help maintain the whole-body temperature through blood circulation or simply cool the large brains of endotherms? If it is to cool their brain, endotherms with larger brains might have larger nasal cavities and efficient cooling aided by turbinates. To test that, the researchers aimed to clarify the primary role of respiratory turbinates and the physiological function of the nasal cavity of non-avian dinosaurs and their living descendants.

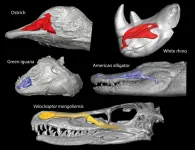

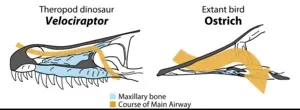

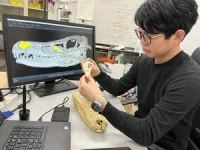

The team studied the head specimens of 51 present-day endotherms and ectotherms, and a skull of a theropod dinosaur called Velociraptor mongoliensis using computer tomography or CT scans and recreating their nasal structures. They found that compared to ectotherms, endotherms have well-developed turbinates and a relatively larger nasal cavity for their head size—and not body size as previously thought. This means that the large nasal cavity helps cool their brain. The researchers also found that the nonflying theropod dinosaur Velociraptor mongoliensis had a smaller nasal cavity and hence couldn’t regulate temperature as efficiently as its present-day descendants, birds, hinting at a relatively less developed brain that did not need an efficient cooling. Perhaps they used other ways of cooling their hot brain; it is still a mystery. The nasal cooling system may have evolved in parallel with changes in their skull structure that we now see in modern endotherms.

Tada was pleasantly surprised by “the possible scenario of the skull evolution seen in the dinosaur-bird lineage nobody had ever noticed before.” He noted, “Our findings highlight the importance of the nose in inferring the physiology of fossil forms such as dinosaurs and enable us to study the evolution of drastic skull modification from the nonflying theropod dinosaurs to modern birds from a new angle.”

Their work appears in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

###

Paper:

Seishiro Tada, Takanobu Tsuihiji, Ryoko Matsumoto, Tomoya Hanai, Yasuko Iwami, Naoki Tomita, Hideaki Sato, and Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar. Evolutionary process toward avian-like cephalic thermoregulation system in Theropoda elucidated based on nasal structures. 2023. Royal Society Open Science. DOI: 10.1098/rsos.220997

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.220997

Funding:

This research was supported by Sasakawa Scientific Research Grant 2021-5012 of the Japan Science Society, JSPS Overseas Challenge Program for Young Researchers, KAKENHI grant no. 22J11553 and 17K05698, and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture Sports, Science & Technology in Japan.

Research Contact:

Seishiro Tada

Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo

Hongo 7-3-1, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033

Email: stada@kahaku.go.jp

Press contact:

Ravindra Palavalli-Nettimi, PhD

School of Science, The University of Tokyo,

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan

ravindra.pn@mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

@Utokyo_science

Related Links:

The School of Science, UTokyo: https://www.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/

END

How to cool your brain? These warm-blooded animals use their nose

Nasal structures, called respiratory turbinates, offer a clue to the evolution of nasal cooling in warm-blooded animal descendants of theropod dinosaurs

2023-04-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

It’s all in the wrist: energy-efficient robot hand learns how not to drop the ball

2023-04-12

Researchers have designed a low-cost, energy-efficient robotic hand that can grasp a range of objects – and not drop them – using just the movement of its wrist and the feeling in its ‘skin’.

Grasping objects of different sizes, shapes and textures is a problem that is easy for a human, but challenging for a robot. Researchers from the University of Cambridge designed a soft, 3D printed robotic hand that cannot independently move its fingers but can still carry out a range of complex movements.

The robot hand was trained to ...

How an African bird might inspire a better water bottle

2023-04-12

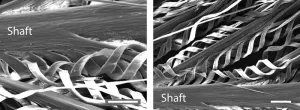

An extreme closeup of feathers from a bird with an uncanny ability to hold water while it flies could inspire the next generation of absorbent materials.

With high resolution microscopes and 3D technology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology captured an unprecedented view of feathers from the desert-dwelling sandgrouse, showcasing the singular architecture of their feathers and revealing for the first time how they can hold so much water.

“It’s super fascinating to see how nature managed to create structures so perfectly efficient to take ...

Time-restricted fasting could cause fertility problems

2023-04-12

Time-restricted fasting diets could cause fertility problems according to new research from the University of East Anglia.

A new study published today shows that time-restricted fasting affects reproduction differently in male and female zebrafish.

Importantly, some of the negative effects on eggs and sperm quality can be seen after the fish returned to their normal levels of food consumption.

The research team say that while the study was conducted in fish, their findings highlight the importance of considering not just the effect of fasting on weight and health, but also on fertility.

Prof Alexei Maklakov, from UEA’s School of Biological Sciences, said: “Time-restricted ...

Scientists uncover the amazing way sandgrouse hold water in their feathers

2023-04-12

Many birds’ feathers are remarkably efficient at shedding water — so much so that “like water off a duck’s back” is a common expression. Much more unusual are the belly feathers of the sandgrouse, especially Namaqua sandgrouse, which absorb and retain water so efficiently the male birds can fly more than 20 kilometers from a distant watering hole back to the nest and still retain enough water in their feathers for the chicks to drink and sustain themselves in the searing deserts ...

Alternative route used by specialized immune cells to colonize the embryonic brain suggests new approach to fighting fetal brain dysfunction

2023-04-12

A team from the Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan has uncovered new information about how microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain, colonize the brain during the embryonic stage of development. Although erythromyeloid progenitors (EMPs) were previously thought to divide into either microglia or macrophages, the group found that macrophages that enter the brain primordium —the brain in its earliest recognizable stage of development— can become microglia at later stages of development. These findings demonstrate the plasticity of these ...

The brain’s cannabinoid system protects against addiction following childhood maltreatment

2023-04-12

High levels of the body’s own cannabinoid substances protect against developing addiction in individuals previously exposed to childhood maltreatment, according to a new study from Linköping University in Sweden. The brains of those who had not developed an addiction following childhood maltreatment seem to process emotion-related social signals better.

Childhood maltreatment has long been suspected to increase the risk of developing a drug or alcohol addiction later in life. Researchers at Linköping University have previously shown that this risk is three times higher if you have been exposed to childhood maltreatment ...

Pregnant women show robust and variable immunity during COVID-19

2023-04-12

New research from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) has found that pregnant women display a strong immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, comparable to that of non-pregnant women.

Published in JCI Insight, the study looked at the immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in unvaccinated pregnant and non-pregnant women and found similar levels of antibodies and T and B cell responses, responsible for long-term protection.

Lead author of the paper, University of ...

Antimicrobial stewardship programs essential for preventing C. difficile in hospitals

2023-04-12

ARLINGTON, Va. (April 12, 2023) — Five medical organizations say it is essential that hospitals establish antimicrobial stewardship programs to prevent Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infections. These infections, linked to antibiotic use, cause difficult-to-treat diarrhea, longer hospital stays, and higher costs. C. difficile infections are fatal for more than 12,000 people in the United States each year.

Strategies to Prevent Clostridioides difficile Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2022 Update, gives evidence-based, ...

Mitochondria power-supply failure may cause age-related cognitive impairment

2023-04-12

LA JOLLA—(April 12, 2023) Brains are like puzzles, requiring many nested and codependent pieces to function well. The brain is divided into areas, each containing many millions of neurons connected across thousands of synapses. These synapses, which enable communication between neurons, depend on even smaller structures: message-sending boutons (swollen bulbs at the branch-like tips of neurons), message-receiving dendrites (complementary branch-like structures for receiving bouton messages), and power-generating mitochondria. To create a cohesive brain, all these pieces must be accounted for.

However, in the aging brain, these ...

Education and peer support cut binge-drinking by National Guard members in half, study shows

2023-04-12

A new study shows promise for reducing risky drinking among Army National Guard members over the long term, potentially improving their health and readiness to serve.

The number of days each month that Guard members said they had been binge-drinking dropped by up to half, according to the new findings by a University of Michigan team published in the journal Addiction.

The drop happened over the course of a year among Guard members who did multiple brief online education sessions designed for members of the military, and among those who did an initial online education session followed by supportive ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

Power grids to epidemics: study shows small patterns trigger systemic failures

[Press-News.org] How to cool your brain? These warm-blooded animals use their noseNasal structures, called respiratory turbinates, offer a clue to the evolution of nasal cooling in warm-blooded animal descendants of theropod dinosaurs