(Press-News.org) Reducing global greenhouse gas emissions is critical to avoiding a climate disaster, but current carbon removal methods are proving to be inadequate and costly. Now researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, have proposed a scalable solution that uses simple, inexpensive technologies to remove carbon from our atmosphere and safely store it for thousands of years.

As reported today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers propose growing biomass crops to capture carbon from the air, then burying the harvested vegetation in engineered dry biolandfills. This unique approach, which researchers call agro-sequestration, keeps the buried biomass dry with the aid of salt to suppress microbials and stave off decomposition, enabling stable sequestration of all the biomass carbon.

The result is carbon-negative, making this approach a potential game changer, according to Eli Yablonovitch, lead author and Professor in the Graduate School in UC Berkeley’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences.

“We’re claiming that proper engineering can solve 100% of the climate crisis, at manageable cost,” said Yablonovitch. “If implemented on a global scale, this carbon-negative sequestration method has the potential to remove current annual carbon dioxide emissions as well as prior years’ emissions from the atmosphere.”

Unlike prior efforts toward carbon neutrality, agro-sequestration seeks not net carbon neutrality, but net carbon negativity. According to the paper, for every metric ton (tonne) of dry biomass, it would be possible to sequester approximately 2 tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Agro-sequestration: A way to stably sequester carbon in buried biomass

The idea of burying biomass in order to sequester carbon has been gaining popularity, with startup organizations burying everything from plants to wood. But ensuring the stability of the buried biomass is a challenge. While these storage environments are devoid of oxygen, anaerobic microorganisms can still survive and cause the biomass to decompose into carbon dioxide and methane, rendering these sequestration approaches carbon-neutral, at best.

But there is one thing that all life forms require — moisture, rather than oxygen. This is measured by “water activity,” a quantity similar to relative humidity. If internal water activity falls below 60%, all life comes to a halt — a concept underpinning the UC Berkeley researchers’ new agro-sequestration solution.

“There are significant questions concerning long-term sequestration for many of these recently popularized nature- and agriculturally-based technologies,” said Harry Deckman, co-author of the study and a researcher in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences. “The agro-sequestration approach we’re proposing can stably sequester the carbon in dried salted biomass for thousands of years, with less cost and higher carbon efficiency than these other air capture technologies.”

Hugh Helferty, co-founder and president of Producer Accountability for Carbon Emissions (PACE), a nonprofit committed to attaining global net zero emissions by 2050, sees great promise in this solution. “Agro-sequestration has the potential to transform temporary nature-based solutions into permanent CO2 storage,” said Helferty, who is not involved with the study. “By developing their approach, Deckman and Yablonovitch have created an invaluable new option for tackling climate change.”

Achieving the right level of dryness to prevent decomposition

Living cells must be able to transfer water-solubilized nutrients and water-solubilized waste across their cell walls to survive. According to Deckman, decreasing the water activity below 60% has been shown to stop these metabolic processes.

To achieve the necessary level of dryness, Yablonovitch and Deckman took inspiration from a long-term food preservation technique dating back to Babylonian times: salt.

“Dryness, sometimes assisted by salt, effectively reduces the internal relative humidity of the sequestered biomass,” said Yablonovitch. “And that has been proven to prevent decomposition for thousands of years.”

Researchers point to a date palm named Methuselah as proof that biomass, if kept sufficiently dry, can be preserved well beyond the next millennium.

In the 1960s, Israeli archaeologist Yigal Yadin discovered date palm seeds among ancient ruins atop Masada, a mesa overlooking the Dead Sea — one of the most arid places in the world. The seeds remained in a drawer for more than 40 years, until Sarah Sallon, a doctor researching natural medicines, requested them in 2005. After having the seeds carbon-dated, she learned that they were 2,000 years old and then asked horticulturist Elaine Solowey to plant them. They germinated, and Methuselah, one of those date palms, continues to thrive today.

“This is proof that if you keep biomass dry, it will last for hundreds to thousands of years,” said Yablonovitch. “In other words, it is a natural experiment that proves you can preserve biomass for 2,000 years.”

A cost-effective, scalable approach

In addition to offering long-term stability, Yablonovitch and Deckman’s agro-sequestration approach is extremely cost effective. Together, the agriculture and biolandfill costs total US$60 per tonne of captured and sequestered carbon dioxide. (By comparison, some direct air capture and carbon dioxide gas sequestration strategies cost US$600 per tonne.)

“Sixty dollars per tonne of captured and sequestered carbon dioxide corresponds to an added cost of $0.53 per gallon of gasoline,” said Yablonovitch. “At this price, offsetting the world’s carbon dioxide emissions would set back the world economy by 2.4%.”

The researchers have compiled a list of more than 50 high-productivity plants capable of being grown in diverse climates worldwide and with dry biomass yields in a range from 4 to more than 45 dry tonnes per hectare. All have been selected for their carbon-capturing abilities.

This solution also can scale without encroaching upon or competing with farmland used to grow food. Many of these biomass crops can be grown on marginal pasture and forest lands, or even on farmland that has remained fallow.

“To remove all the carbon that’s produced would require a lot of farmland, but it’s an amount of farmland that is actually available,” said Yablonovitch. “This would be a great boon to farmers, as there is farmland that is currently underutilized.”

Farmers harvesting these biomass crops would dry the plants, then entomb them in a dry engineered biolandfill located within the agricultural regions, tens of meters underground and safe from human activity and natural disasters.

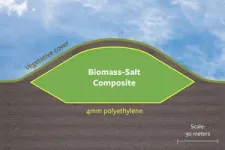

The researchers based their design of these dry tomb structures on current municipal landfill best practices, but added enhancements to ensure dryness, such as two 2-millimeter-thick nested layers of polyethylene encasing the biomass, a practice already used in modern landfills.

The landfill area would cover only a tiny portion — 0.0001% — of the agricultural area. In other words, 10,000 hectares of biomass production could be buried in a 1-hectare biolandfill. In addition, the top surface of the landfill could be restored to agricultural production afterward.

A fast path to adoption

The timeline for adoption of this carbon capture and sequestration method could be short, according to Deckman. “Agro-sequestration is technologically ready, and construction of the engineered biolandfills could begin after one growing season,” he said.

Yablonovitch and Deckman’s analysis shows that farmers could make the transition to biomass agriculture rather quickly. They estimate that it would take about one year to convert existing farmland to biomass agriculture, but longer for virgin land that lacks the infrastructure needed to support agriculture. The biomass crops would be ready for harvest and sequestration within a growing season.

Using this approach, the researchers calculated that sequestering approximately half of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions — about 20 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide per year — would require agricultural production from an area equal to one-fifth of the world’s row cropland or one-fifteenth of the land area for all croplands, pastures and forests. According to their report, this amount of land is the same or less than the total area that many of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s models for greenhouse reduction are considering for biomass production.

“Our approach to agro-sequestration offers many benefits in terms of cost, scalability and long-term stability,” said Yablonovitch. “In addition, it uses existing technologies with known costs to provide a practical path toward removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and solving the climate change problem. Nonetheless, society must continue its efforts toward de-carbonization; developing and installing solar and wind technologies; and revolutionizing energy storage.”

END

To more effectively sequester biomass and carbon, just add salt

Salting and burying biomass in dry landfills can economically capture GHGs for millennia

2023-04-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How to cool your brain? These warm-blooded animals use their nose

2023-04-12

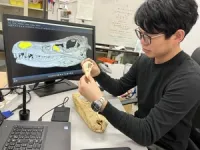

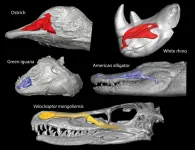

A research team led by Seishiro Tada and Takanobu Tsuihiji of the University of Tokyo shows that the living warm-blooded descendants of theropod dinosaurs evolved a better nasal cooling system aided by larger nasal cavities than cold-blooded animals. The study provides clues to the evolution of nasal cooling in warm-blooded animals from their theropod dinosaur ancestors.

Endotherms, or warm-blooded animals, maintain their high body temperature through internal heat sources. Birds, humans, and other mammals are endotherms. But ectotherms, or cold-blooded animals such as reptiles, use external heat sources to keep ...

It’s all in the wrist: energy-efficient robot hand learns how not to drop the ball

2023-04-12

Researchers have designed a low-cost, energy-efficient robotic hand that can grasp a range of objects – and not drop them – using just the movement of its wrist and the feeling in its ‘skin’.

Grasping objects of different sizes, shapes and textures is a problem that is easy for a human, but challenging for a robot. Researchers from the University of Cambridge designed a soft, 3D printed robotic hand that cannot independently move its fingers but can still carry out a range of complex movements.

The robot hand was trained to ...

How an African bird might inspire a better water bottle

2023-04-12

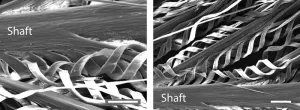

An extreme closeup of feathers from a bird with an uncanny ability to hold water while it flies could inspire the next generation of absorbent materials.

With high resolution microscopes and 3D technology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology captured an unprecedented view of feathers from the desert-dwelling sandgrouse, showcasing the singular architecture of their feathers and revealing for the first time how they can hold so much water.

“It’s super fascinating to see how nature managed to create structures so perfectly efficient to take ...

Time-restricted fasting could cause fertility problems

2023-04-12

Time-restricted fasting diets could cause fertility problems according to new research from the University of East Anglia.

A new study published today shows that time-restricted fasting affects reproduction differently in male and female zebrafish.

Importantly, some of the negative effects on eggs and sperm quality can be seen after the fish returned to their normal levels of food consumption.

The research team say that while the study was conducted in fish, their findings highlight the importance of considering not just the effect of fasting on weight and health, but also on fertility.

Prof Alexei Maklakov, from UEA’s School of Biological Sciences, said: “Time-restricted ...

Scientists uncover the amazing way sandgrouse hold water in their feathers

2023-04-12

Many birds’ feathers are remarkably efficient at shedding water — so much so that “like water off a duck’s back” is a common expression. Much more unusual are the belly feathers of the sandgrouse, especially Namaqua sandgrouse, which absorb and retain water so efficiently the male birds can fly more than 20 kilometers from a distant watering hole back to the nest and still retain enough water in their feathers for the chicks to drink and sustain themselves in the searing deserts ...

Alternative route used by specialized immune cells to colonize the embryonic brain suggests new approach to fighting fetal brain dysfunction

2023-04-12

A team from the Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan has uncovered new information about how microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain, colonize the brain during the embryonic stage of development. Although erythromyeloid progenitors (EMPs) were previously thought to divide into either microglia or macrophages, the group found that macrophages that enter the brain primordium —the brain in its earliest recognizable stage of development— can become microglia at later stages of development. These findings demonstrate the plasticity of these ...

The brain’s cannabinoid system protects against addiction following childhood maltreatment

2023-04-12

High levels of the body’s own cannabinoid substances protect against developing addiction in individuals previously exposed to childhood maltreatment, according to a new study from Linköping University in Sweden. The brains of those who had not developed an addiction following childhood maltreatment seem to process emotion-related social signals better.

Childhood maltreatment has long been suspected to increase the risk of developing a drug or alcohol addiction later in life. Researchers at Linköping University have previously shown that this risk is three times higher if you have been exposed to childhood maltreatment ...

Pregnant women show robust and variable immunity during COVID-19

2023-04-12

New research from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) has found that pregnant women display a strong immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, comparable to that of non-pregnant women.

Published in JCI Insight, the study looked at the immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in unvaccinated pregnant and non-pregnant women and found similar levels of antibodies and T and B cell responses, responsible for long-term protection.

Lead author of the paper, University of ...

Antimicrobial stewardship programs essential for preventing C. difficile in hospitals

2023-04-12

ARLINGTON, Va. (April 12, 2023) — Five medical organizations say it is essential that hospitals establish antimicrobial stewardship programs to prevent Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infections. These infections, linked to antibiotic use, cause difficult-to-treat diarrhea, longer hospital stays, and higher costs. C. difficile infections are fatal for more than 12,000 people in the United States each year.

Strategies to Prevent Clostridioides difficile Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2022 Update, gives evidence-based, ...

Mitochondria power-supply failure may cause age-related cognitive impairment

2023-04-12

LA JOLLA—(April 12, 2023) Brains are like puzzles, requiring many nested and codependent pieces to function well. The brain is divided into areas, each containing many millions of neurons connected across thousands of synapses. These synapses, which enable communication between neurons, depend on even smaller structures: message-sending boutons (swollen bulbs at the branch-like tips of neurons), message-receiving dendrites (complementary branch-like structures for receiving bouton messages), and power-generating mitochondria. To create a cohesive brain, all these pieces must be accounted for.

However, in the aging brain, these ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

Power grids to epidemics: study shows small patterns trigger systemic failures

[Press-News.org] To more effectively sequester biomass and carbon, just add saltSalting and burying biomass in dry landfills can economically capture GHGs for millennia