(Press-News.org) AUGUSTA, Ga. (April 25, 2023) – The first in-human-study of a new immunotherapy that blocks a natural enzyme tumors commandeer for their protection was well tolerated by children with relapsed brain tumors and enabled many to have unexpected months of a more normal life, researchers say.

“Our kids were by and large out of the hospital and going about their daily activities. They were in school, we had young adults who were in college living in a dorm on their own, taking their medicine on their own and coming to see us once a month,” says Theodore S. Johnson, MD/PhD, pediatric hematologist/oncologist and co-director of the Pediatric Immunotherapy Program at Children’s Hospital of Georgia and the Georgia Cancer Center.

The phase 1 trial of indoximod plus chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, started in 2015 at CHOG and Children’s Hospital of Atlanta. Researchers enrolled 81 children ages 3 to 21 from across the country with all types of brain tumors that had relapsed or never resolved, which is called progression. About midway through the trial, the researchers added children newly diagnosed with a rare, aggressive diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, or DIPG, which can’t be treated surgically and for which there is currently no treatment considered curative.

Johnson presented an analysis of the safety, tolerability and five-year outcomes of the phase 1 trial during the American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting April 22-27 in Boston.

Indoximod inhibits IDO, or indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase, an enzyme both fetuses and brain tumors use to hide from the immune system. The IDO inhibitor helps prevent the tumor from using IDO to suppress the natural response of the immune system to an invader like a tumor. Johnson notes that IDO-inhibitors do not work alone, rather, as with the trial, in combination with chemotherapy, radiation or targeted therapy, which target molecular mechanisms tumors use to grow.

Assessing the safety and optimal dose of the indoximod was the primary endpoint of this and other phase 1 trials, Johnson notes. A follow-on phase 2 trial with a focus on efficacy and funded in part by the National Cancer Institute already is underway once again at CHOG and CHOA, as well as Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

While the majority of the children in the phase 1 trial experienced some side effects like vomiting and anemia, the majority of the side effects were mild; the most serious side effects, including cardiac arrest and stroke, were directly attributable to brain tumor progression, Johnson and his colleagues report.

They approached the study with quality of life for the children top of mind. “We structured the treatment so the chemotherapy would not be highly intensive, and it’s all oral chemotherapy,” Johnson says. “It’s not the same intensity as those high-dose intravenous regimens that drive a lot of severe side effects and very low blood counts that make you need transfusions, make you susceptible to infection and put you in the hospital for infections and other things.”

Several of the young patients in the first-phase trial were already taking temozolomide, a chemotherapy drug commonly prescribed for brain tumors, and their tumors were progressing. But adding the IDO inhibitor to their regimen created a whole new treatment, Johnson says.

“It helps bring the immune system into play. A combination seems to be better because you are hitting the tumor with drugs with different mechanisms of action,” Johnson says, a common approach in today’s cancer treatment. “And, of course, the idea of the IDO inhibitor therapy is we hope to unleash a more powerful immune response.”

The researchers are still analyzing and planning to publish laboratory findings on the overall immune response from the treatment regimen. Detailed, high-throughput immune testing on the DIPG patients indicated a marked increase in the activity of immune cells called T cells, key drivers of the immune response, after staring treatment that included the IDO inhibitor-based therapy.

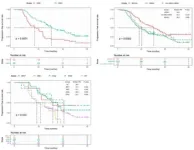

The median survival time in the trial was 13.6 months, while the median survival for children in relapse with the brain tumor types included in the study is about six months, according to the latest literature. A handful of study patients are still alive five years off the study, Johnson says, and one is still on the therapy.

The children with DIPG had a median survival of 14.4 months, Johnson says. Most children with DIPG are diagnosed before age 7 and live about 9 to 11 months after diagnosis. Because of the small number of children with DIPG enrolled, the results could not be considered statistically significant, meaning a clear correlation between the treatment and the survival time could not be made for the DIPG patients.

“Patterns of response for study participants ranged from relentlessly growing tumors with some kids not even getting the second cycle of treatment to kids who immediately had a shrinking tumor that stayed gone for a period of time,” Johnson says. He notes that just stabilizing one of these tumors is significant because a growing tumor in the brain wants to keep growing, which can wreak havoc with your neurological system, robbing fundamental functions like the ability to walk, talk and swallow. Some patients in the study recovered these basic abilities over time.

For this trial, the researchers did not draw hard lines about when treatment should stop. The children stayed on their treatment as long as it was beneficial, and as long as their symptoms permitted. Some children, for example, eventually lost the ability to swallow, which was essential to pill taking. Those late-stage type symptoms indicate the tumor is putting pressure on important parts of the brain making any treatment problematic, he says. But overall the median survival was better than would be expected for late-stage, relapsed tumors, he reiterates.

The study also had the flexibility to switch chemotherapy drugs when needed if the tumor had become resistant, called adaptive management, and this allowed patients to continue with the immunotherapy. They had 18 patients switch to an alternative chemotherapy regimen plus indoximod and the median overall survival for that group was 34.7 months.

“Switching the chemotherapy clearly made an impact in that group but it needs to be studied in more detail,” Johnson says, with more patients with the same tumor type — a goal of the phase 2 study that is underway — to ensure they did not just happen to get patients who were particularly sensitive to the second chemotherapy regimen.

The cancer also can become resistant to immunotherapy, which is why the researchers began looking for another immunotherapy with a different path of action than indoximod. That led to a new phase 1 trial, which is pairing indoximod with a second immunotherapy drug ibrutinib plus chemotherapy. “We think it will magnify the immune effects in a synergistic way,” Johnson says.

Palliative radiation, surgery or the corticosteroid dexamethasone, which may be used to treat fluid buildup in the brain, also were permitted as needed by patients.

Overall the phase 1 trial was “absolutely” a success, Johnson says, noting that while pediatric phase 1 trials are typically hard to recruit for they were able to enroll their target of 81 kids in three years. Also, the vast majority of phase 1 trials don’t have findings sufficient to support moving to phase 2.

“The phase 1 trial met its goals of delivering the treatment safely, proving that the treatment in combination with chemotherapy and radiation is feasible and in determining the best, safe dose of indoximod for both of those combinations,” Johnson says.

David Munn, MD, Johnson’s colleague who is co-director of the Pediatric Immunotherapy Program, was part of the team that reported in 1998 in the journal Science that the placenta expresses IDO to help protect the fetus, which has DNA from both parents, from the mother’s immune response. The MCG researchers would later find that tumors induce IDO as well, likely from the immune system itself, which produces the enzyme as part of a natural check and balance.

Brain tumors are the most common tumor in children and leukemia the most common cancer, according to the American Cancer Society.

Other tumor types in the phase 1 trial included ependymoma, a tumor that begins in the cells that line the passageway for cerebrospinal fluid in the brain and spinal cord; medulloblastoma, which tends to start at the base of the brain and spread to other areas of the brain and spinal cord; and glioblastoma, a fast-growing tumor that develops in the brain cells that support neurons.

Johnson and Munn also are currently working with Dr. Rafal Pacholczyk, director of The Immune Monitoring Shared Resource Laboratory at the Georgia Cancer Center, on developing a flow cytometry test that will indicate how the immune system is responding to the immunotherapy regimens. The test could be done more quickly and ideally less expensively in the future so results could be used to monitor and/or alter the child’s treatment course in real time. The deep sequencing studies they have already done on patients in the phase 1 trial will help identify markers for the new flow cytometry tests.

Augusta University holds patents on the IDO-inhibitor drug indoximod. Lumos Pharma, Inc. (formerly NewLink Genetics Corp.), a biopharmaceutical company based in Austin, Texas and Ames, Iowa, produces the drug and partially funded the phase 1 clinical trial.

Munn and Johnson also are affiliated scientists of MCG’s Immunology Center of Georgia.

For more information about the studies, contact Taylor King, nurse navigator, at 706-721-2949 or tayking@augusta.edu.

END

Novel treatment regimen appears well tolerated, beneficial to children with relapsed brain tumors

2023-04-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Signs you could be suffering from racial trauma – and tools for healing, according to therapists

2023-04-25

In the United States, depression and anxiety are on the rise in African Americans and the evidence suggests that racism is a contributing factor, creating a ripple effect on mental health.

Janeé M. Steele Ph.D. and Charmeka S. Newton, Ph.D. are licensed mental health professionals and scholars who specialize in culturally responsive therapy. They say: “In the Black community there can be a real resistance to our own trauma – for example, if I wasn’t exposed to physical abuse, is it really that bad?

“But this kind of systemic, permeating racism that exists all ...

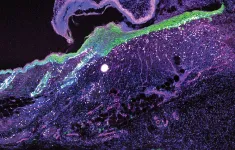

Researchers reveal an ancient mechanism for wound repair

2023-04-24

It’s a dangerous world out there. From bacteria and viruses to accidents and injuries, threats surround us all the time. And nothing protects us more steadfastly than our skin. The barrier between inside and out, the body’s largest organ is also its most seamless defense.

And yet the skin is not invincible. It suffers daily the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, and it tries to keep us safe by sensing and responding to these harms. A primary method is the detection of a pathogen, which kicks the immune system into action. But new research from the lab of Rockefeller’s Elaine Fuchs, published in Cell, reveals an alternative protective ...

Using superconductors to move people, cargo and energy through one combined system

2023-04-24

The promise of superconductivity for electrical power transmission and transportation has long been held back by high costs. Now researchers from the University of Houston and Germany have demonstrated a way to cut the cost and upend both the transit and energy transport sectors by using superconductors to move people, cargo and energy along existing highway infrastructure.

The combined system would not only lower the cost of operating each system but would also provide a way to store and transport liquified hydrogen, an important ...

Brian Clark selected to speak, presented discoveries at NIH workshop and in Journal of Gerontology

2023-04-24

Ohio University Professor of Physiology and Executive Director of the Ohio Musculoskeletal and Neurological Institute (OMNI) Brian Clark Ph.D. was one of 40 expert leaders in the field of aging from around the world chosen to present at a workshop hosted by the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) National Institute on Aging (NIA) on the development of function promoting therapies for age-related weakness. Clark was also asked by the NIH to publish a comprehensive review of his research over the past decade in the Journal of Gerontology.

The workshop covered ...

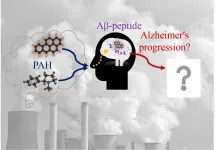

Increased risk of Alzheimer's disease due to exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

2023-04-24

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are typical organic compounds found in cigarette smoke and vehicle exhaust. In addition, PAHs are produced from incomplete combustion of organic material and cooking. The highest concentrations of PM-bound PAHs ranged from 550 ng/m3 to 39000 ng/m3, were observed in Chinese kitchens, fire stations, and ships. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons may combine with ultrafine particles (UFPs) in the air to form particle-bound PAHs. PM0.1 may adsorb large amounts of toxic organic compounds, and long-term exposure to indoor UFPs from cooking resulted in ...

This gel stops brain tumors in mice. Could it offer hope for humans?

2023-04-24

Medication delivered by a novel gel cured 100% of mice with an aggressive brain cancer, a striking result that offers new hope for patients diagnosed with glioblastoma, one of the deadliest and most common brain tumors in humans.

“Despite recent technological advancements, there is a dire need for new treatment strategies,” said Honggang Cui, a Johns Hopkins University chemical and biomolecular engineer who led the research. “We think this hydrogel will be the future and will supplement current treatments for brain cancer.”

Cui’s team combined an anticancer drug and ...

New tools capture economic benefit of restoring urban streams

2023-04-24

An interdisciplinary team of researchers has developed a suite of tools to estimate the total economic value of improving water quality in urban streams. The work can assist federal and state agencies charged with developing environmental regulations affecting urban ecosystems across the Piedmont Region of the United States, which stretches from Maryland to Alabama.

“Urban streams are ubiquitous and face a number of stressors from rapid economic development,” says Roger von Haefen, professor of agricultural and resource economics at North Carolina State University and corresponding ...

A blinking fish reveals clues as to how our ancestors evolved from water to land

2023-04-24

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — An unusual blinking fish, the mudskipper, spends much of the day out of the water and is providing clues as to how and why blinking might have evolved during the transition to life on land in our own ancestors. New research shows that these amphibious fish have evolved a blinking behavior that serves many of the same purposes of our blinking. The results suggest that blinking may be among the suite of traits that evolved to allow the transition to life on land in tetrapods — the group of animals that includes mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians — some 375 million years ago.

The study appears the week ...

New machine-learning method predicts body clock timing to improve sleep and health decisions

2023-04-24

A new machine-learning method could help us gauge the time of our internal body clock, helping us all make better health decisions, including when and how long to sleep.

The research, which has been conducted by the University of Surrey and the University of Groningen, used a machine learning programme to analyse metabolites in blood to predict the time of our internal circadian timing system.

To date the standard method to determine the timing of the circadian system is to measure the timing of our ...

Health surveys, studies exclude trans people and gender-diverse communities, impacting health care

2023-04-24

ANN ARBOR—Health surveys and clinical studies have a data collection problem: Because of the way they record sex or gender, they often exclude transgender and gender-diverse people, according to University of Michigan research.

Most studies and surveys either ask participants for their sex, a biological construct, or their gender, a social construct. In this way, they only consider either sex or gender independently or use the two concepts interchangeably, says Kate Duchowny, a research assistant professor in the Survey Research Center at the U-M Institute for Social Research.

Participants either respond with their sex assigned at birth or the ...