(Press-News.org)

Ikoma, Japan – Cell membranes play a critical role by serving as containment units and separating the inner cellular space from the extracellular environment. Proteins with distinct functional units play a key role in facilitating protein-membrane interactions. For instance, “Bin-Amphiphysin-Rvs” (“BAR”) domain proteins are involved in regulating cell membrane curvature. This physical bending of cell membranes helps cells carry out various biologically important processes such as endocytosis and cell motility. Although BAR proteins drive membrane curvature by assembling into highly ordered oligomeric units, the underlying mechanism regulating this phenomenon remains largely unknown.

Now, a study by researchers from Japan revealed the mechanism that drives the oligomeric assembly of a BAR-domain-containing protein on membrane surfaces. The study, published in the journal Science Advances, was led by Shiro Suetsugu, Wan Nurul Izzati Wan Mohamad Noor, and Nhung Thi Hong Nguyen from Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST).

Speaking about the study, Suetsugu says, “The relatively small number of oligomeric BAR domains on narrow membrane tubules makes it difficult to analyze their assembly. We thus used fluorescence resonance energy transfer monitoring to analyze the oligomeric assembly of F-BAR-containing GAS7 protein, because oligomeric GAS7 assembles into larger than the others.”

To elucidate the mechanism involved in the assembly of GAS7 on membrane surfaces, the researchers employed a technique called fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). In this method, the researchers labeled GAS7b units with fluorescent protein tags to monitor the magnitude and timing of GAS7 assembly. The observation of fluorescence emission indicated that GAS7 assembly on lipid membrane surfaces was a rapid process and started within seconds. This process was enhanced by the presence of several proteins, including the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)/N-WASP, WISH, Nck, the activated small GTPase Cdc42, and a membrane-anchored phagocytic receptor.

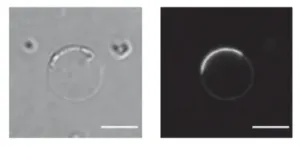

The assembly of GAS7 on the membrane was also examined by microscope, using giant membrane vesicles. The protein should bind to the membrane uniformly if it does not oligomerize but GAS7 clearly accumulated at the part of the membrane, demonstrating the oligomeric assembly by the presence of those proteins (Figure).

The team further examined the role of WASP in GAS7 assembly. WASP undergoes mutations in patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, which is associated with various immunological disorders. In this regard, the researchers saw that the regulated GAS7 assembly was abolished by the WASP mutations both in vitro as well as during phagocytosis (the cell-membrane-mediated engulfment of large particles). The latter, according to the researchers, was striking, because GAS7 is known to be involved in phagocytosis. Therefore, the analyses provided an explanation for the defective phagocytosis seen in macrophages from patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.

In conclusion, WASP, Cdc42, and the other proteins that commonly bind to the BAR domain superfamily proteins promote GAS7 assembly on lipid membranes. Moreover, BAR domain assembly on membrane surfaces serves as a “scaffold” or platform for the binding of other proteins, which further facilitates protein signaling beneath the surface. Summarizing the results, Suetsugu concludes, “Since WASP protein commonly binds to the BAR superfamily of proteins, the mechanism of assembly observed here is likely to function for other BAR proteins as well. We believe that our study provides breakthrough information for studies on cellular shape formation and protein condensate studies.”

###

Resource

Title: Small GTPase Cdc42, WASP, and scaffold proteins for higher order assembly of the F-BAR domain protein

Authors: Wan Nurul Izzati Wan Mohamad Noor, Nhung Thi Hong Nguyen, Theng Ho Cheong, Min Fey Chek, Toshio Hakoshima, Takehiko Inaba, Kyoko Hanawa-Suetsugu, Tamako Nishimura, Shiro Suetsugu

Journal: Science Advances

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adf5143

Information about the Molecular Medicine and Cell Biology Laboratory can be found at the following website: https://bsw3.naist.jp/eng/courses/courses210.html

About Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST)

Established in 1991, Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST) is a national university located in Kansai Science City, Japan. In 2018, NAIST underwent an organizational transformation to promote and continue interdisciplinary research in the fields of biological sciences, materials science, and information science. Known as one of the most prestigious research institutions in Japan, NAIST lays a strong emphasis on integrated research and collaborative co-creation with diverse stakeholders. NAIST envisions conducting cutting-edge research in frontier areas and training students to become tomorrow's leaders in science and technology.

END

Philadelphia, April 26, 2023 – Researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and Princeton University have discovered a novel genetic disorder associated with neurodevelopmental differences. The discovery identified the disorder in 21 families from all over the world. The findings were published today in Science Advances.

The as-yet unnamed disorder is the result of a series of rare variants in the MAP4K4 gene, which is involved in many signaling pathways, including the RAS pathway ...

Almost one in three adults aged 45 and older who had both TB and COVID-19 died during a pandemic cohort study in NYC between March 2020 and June 2022.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0001758

Article Title: Cohort study of the mortality among patients in New York City with tuberculosis and COVID-19, March 2020 to June 2022

Author Countries: USA

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work. END ...

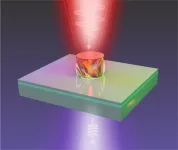

Physicists at The Australian National University (ANU) are using nanoparticles to develop new sources of light that will allow us to “peel back the curtain” into the world of extremely small objects – thousands of times smaller than a human hair – with major gains for medical and other technologies.

The findings, published in Science Advances, could have major implications for medical science by offering an affordable and effective solution to analyse tiny objects that are too small for microscopes to see, let alone the human eye. The work could also be beneficial for the semiconductor industry ...

Keeping tree diversity intact in Canada’s many forests over the long term can help increase carbon capture and mitigate climate change, according to a new University of Alberta study.

The study, published in Nature, is the first of its kind to show the sustained benefits of tree diversity on a large spatial scale, in terms of storing carbon and nitrogen in the soil. It reinforces the importance of biodiversity conservation in forests, says Xinli Chen, lead author on the paper and postdoctoral fellow in the Faculty of Agricultural, ...

Andy Weir’s bestselling 2011 book, The Martian, features botanist Mark Watney’s efforts to grow food on Mars after he becomes stranded there. While Watney’s initial efforts focus on growing potatoes, new research presented at the 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference by a team of interdisciplinary researchers from the U of A suggests future Martian botanists like Watney may have a better option: growing rice.

As outlined in the team’s abstract, Rice Can Grow and Survive in Martian ...

ITHACA, N.Y. -- New research from a multidisciplinary team helps to illuminate the mechanisms behind circadian rhythms, offering new hope for dealing with jet lag, insomnia and other sleep disorders.

Using innovative cryo-electron microscopy techniques, the researchers have identified the structure of the circadian rhythm photosensor and its target in fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), one of the major organisms used to study circadian rhythms. The research, “Cryptochrome-Timeless Structure Reveals Circadian Clock Timing ...

The Buck Institute for Research on Aging announces that Ashley Webb, PhD, will join its faculty as an associate professor on August 1, 2023. Webb’s research is focused on the molecular mechanisms underlying stem cells and brain aging. She joins the Buck from Brown University, where she is currently an associate professor in the Department of Molecular Biology, Cell Biology and Biochemistry. Webb uses a combination of mouse models, cell culture approaches and genomics technologies to investigate the epigenetic and transcriptional mechanisms that preserve healthy ...

Preserving the diversity of forests assures their productivity and potentially increases the accumulation of carbon and nitrogen in the soil, which helps to sustain soil fertility and mitigate global climate change.

That's the main takeaway from a new study that analyzed data from hundreds of plots in Canada's National Forest Inventory to investigate the relationship between tree diversity and changes in soil carbon and nitrogen in natural forests.

Numerous biodiversity-manipulation experiments have collectively suggested that ...

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) identify a novel mechanism by which cells adhere more strongly to their surrounding matrix in response to stress

Tokyo, Japan – The DNA molecules in our cells can be damaged by various extrinsic and intrinsic factors called genotoxic stressors; persistent and unchecked damage can lead to developing diseases like cancer. Fortunately, our cells don’t sit idly by and let this happen.

In a recent article published in Cell Death & Disease, a team ...

Researchers have established that biological sex plays a role in determining an individual’s risk of brain disorders. For example, boys are more likely to be diagnosed with behavioral conditions like autism or attention deficit disorder, whereas women are more likely to suffer from anxiety disorders, depression, or migraines. However, experts do not fully understand how sex contributes to brain development, particularly in the context of these diseases. They think, in part, it may have something to do with the differing sizes of certain brain regions.

University ...