(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY (May 2, 2023)--A study of more than 2,200 adults who attended U.S. high schools in the early 1960s found that those who attended higher quality schools had better cognitive function 60 years later.

Previous studies have found that the number of years spent in school correlates with cognition later in life, but few studies have examined the impact of educational quality.

“Our study establishes a link between high-quality education and better late-life cognition and suggests that increased investment in schools, especially those that serve Black children, could be a powerful strategy to improve cognitive health among older adults in the United States,” says Jennifer Manly, PhD, professor of neuropsychology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and senior author of the study.

Study details

The study, led by Manly and Dominika Šeblová, PhD, a postdoctoral research scientist at Columbia, used data from Project Talent, a 1960 survey of high school students across the United States, and follow-up data collected in the Project Talent Aging Study.

The researchers examined relationships between six indicators of school quality and several measures of cognitive performance in participants nearly 60 years after they left high school.

Since high-quality schools may be especially beneficial for people from disadvantaged backgrounds, the researchers also examined whether associations differed by geography, sex/gender, and race and ethnicity (the survey only included sufficient data from Black and white respondents).

Teacher training linked to late-life cognition in students

The researchers found that attending a school with a higher number of teachers with graduate training was the most consistent predictor of better later-life cognition, especially language fluency (for example, coming up with words within a category). Attending a school with a high number of graduate-level teachers was approximately equivalent to the difference in cognition between a 70-year-old and someone who is one to three years older. Other indicators of school quality were associated with some, but not all, measures of cognitive performance.

Manly and Šeblová say many reasons may explain why attending schools with well-trained teachers may affect later-life cognition. “Instruction provided by more experienced and knowledgeable teachers might be more intellectually stimulating and provide additional neural or cognitive benefits,” Šeblová says, “and attending higher-quality schools may also influence life trajectory, leading to university education and greater earnings, which are in turn linked to better cognition in later life.”

Greater impact on Black students

Though the associations between school quality and late-life cognition were similar between white and Black students, Black participants were more likely to have attended schools of lower quality.

“Racial equity in school quality has never been achieved in the United States and school racial segregation has grown more extreme in recent decades, so this issue is still a substantial problem,” says Manly.

For example, a 2016 survey found that U.S schools attended by non-white students had twice as many inexperienced teachers as schools attended by predominantly white students.

“Racial inequalities in school quality may contribute to persistent disparities in late-life cognitive outcomes for decades to come,” Manly adds.

More information

Jennifer Manly, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Neurology, the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center, and the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain at Columbia University.

The findings were published May 2 in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring in a paper titled “High school quality is associated with cognition 58 years later.”

All authors: Dominika Šeblová (Columbia University, now at Charles University, Prague); Chloe Eng (University of California San Francisco); Justina F. Avila (Columbia); Jordan D. Dworkin (Federation of American Scientists); Kelly Peters (American Institutes for Research); Susan Lapham (American Institutes for Research); Laura B. Zahodne (University of Michigan); Benjamin Chapman (University of Rochester Medical Center); Carol A. Prescott (University of Southern California); Tara L. Gruenewald (Chapman University); Thalida Em. Arpawong (USC); Margaret Gatz (USC); Rich J. Jones (Brown University); Maria M. Glymour (UCSF); and Jennifer J. Manly (Columbia).

The researchers were funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01AG056163 and RF1AG056164), the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, PRIMUS Research Programme at Charles University, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Alzheimer’s Association.

###

Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) is a clinical, research, and educational campus located in New York City. Founded in 1928, CUIMC was one of the first academic medical centers established in the United States of America. CUIMC is home to four professional colleges and schools that provide global leadership in scientific research, health and medical education, and patient care including the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing. For more information, please visit cuimc.columbia.edu.

END

60 years later, high school quality may have a long-term impact on cognition

2023-05-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Too much water can make whiskies taste the same

2023-05-02

RICHLAND, Wash. – While adding a little water is popularly thought to “open up” the flavor of whisky, a Washington State University-led study indicates there’s a point at which it becomes too much: about 20%.

Researchers chemically analyzed how volatile compounds in a set of 25 whiskies responded to the addition of water, including bourbons, ryes, Irish whiskeys and both single malt and blended Scotches. They also had a trained sensory panel assess six of those whiskies, three Scotches and ...

Machine learning model sheds light on how brains recognize communication sounds

2023-05-02

PITTSBURGH, May 2, 2023 — In a paper published today in Communications Biology, auditory neuroscientists at the University of Pittsburgh describe a machine learning model that helps explain how the brain recognizes the meaning of communication sounds, such as animal calls or spoken words.

The algorithm described in the study models how social animals, including marmoset monkeys and guinea pigs, use sound-processing networks in their brain to distinguish between sound categories – such as calls for mating, food or danger — and act on them.

The study is an important step toward understanding the intricacies and complexities ...

Cellular “cruise control” system safeguards RNA levels in Rett syndrome nerve cells

2023-05-02

Every cell in our body is able to turn genes (DNA) on or off, producing RNA, but when genes are ‘turned on’ to the wrong level it can result in a variety of health conditions.

Rett syndrome is a rare neurodevelopmental condition that causes a loss of motor and language skills over time in girls. The condition is caused by a genetic variation in the MECP2 gene located on the X chromosome, resulting in affected nerve cells in the brain expressing the wrong levels of more than one thousand genes. The end result is that Rett syndrome nerve cells are smaller, less interconnected and less electrically active than healthy controls.

In ...

Study finds gender pay differences begin early, with the job search

2023-05-02

A new paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, published by Oxford University Press, indicates that an important part of the pay gap between men and women has to do with how they conduct job searches, with women more likely to accept job offers early while men tend to hold out for higher pay.

Women in the United States earn 84% of what men earn, as of 2020. This disparity is well documented, and economists and the general public have known about the earnings difference for decades. The reasons for this phenomenon are a matter of considerable debate.

Initial conditions in the labor market are long-lasting. Young workers who begin ...

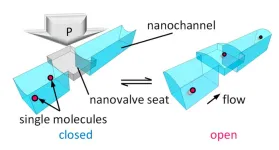

Single-molecule valve: a breakthrough in nanoscale control

2023-05-02

Scientists dream of using tiny molecules as building blocks to construct things, similar to how we build things with mechanical parts. However, molecules are incredibly small - around one hundred millionth the size of a softball - and they move randomly in liquids, making it very difficult to manipulate them in a single form. To overcome this challenge, “nanofluidic devices” that can transport molecules in extremely narrow channels, similar in size to one millionth of a straw, are attracting attention ...

The science behind the life and times of the Earth’s salt flats

2023-05-02

AMHERST, Mass. – Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the University of Alaska Anchorage are the first to characterize two different types of surface water in the hyperarid salars—or salt flats—that contain much of the world’s lithium deposits. This new characterization represents a leap forward in understanding how water moves through such basins, and will be key to minimizing the environmental impact on such sensitive, critical habitats.

“You can’t protect the salars if you don’t first understand how they work,” says Sarah McKnight, lead author of the research that appeared recently ...

HIV status is not associated with mpox treatment outcomes in persons using tecovirimat

2023-05-02

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 01 May 2023

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

----------------------------

1. ...

Juvenile salmon migration timing responds unpredictably to climate change

2023-05-02

Climate change has led to earlier spring blooms for wildflowers and ocean plankton but the impacts on salmon migration are more complicated, according to new research.

In a new study, published in the journal Nature, Ecology & Evolution, Simon Fraser University (SFU) researcher Sam Wilson led a set of diverse collaborators from across North America to compile the largest dataset in the world on juvenile salmon migration timing. The dataset includes 66 populations from Oregon to B.C. to Alaska. Each dataset was at least 20 years in length with the longest dating back to 1951. Only wild salmon, and not salmon from hatcheries, ...

State study: labor induction doesn’t always reduce caesarean birth risk or improve outcomes for term pregnancies

2023-05-02

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – In recent years, experts have debated whether most birthing individuals would benefit from labor induction once they reach a certain stage of pregnancy.

But a new statewide study in Michigan suggests that inducing labor at the 39th week of pregnancy for people having their first births with a single baby that is in a head down position, or low risk, doesn’t necessarily reduce the risk of caesarian births. In fact, for some birthing individuals, it may even have the opposite effect if hospitals don’t take a thoughtful approach to ...

OSU-Cascades researcher explores AI solution for tracking and reducing household food waste

2023-05-02

BEND, Ore. – A researcher at Oregon State University-Cascades has received funding to develop a smart compost bin that tracks household food waste.

The project led by Patrick Donnelly, assistant professor of computer science in the OSU College of Engineering, seeks to make a dent in a multi-billion-dollar annual problem in the United States: More than one-third of all food produced in the U.S. goes uneaten.

“At every other step of the agricultural supply chain, food waste is tracked, measured and quantified,” Donnelly ...