(Press-News.org) In a study tracking climate-induced changes in the distribution of animals and their effects on ecosystem functions, North Carolina State University researchers show that resident species can continue managing some important ecological processes despite the arrival of newcomers that are similar to them, but resident species’ role in ecosystem functioning changes when the newcomers are more different.

The findings could lead to predictive tools for understanding what might happen as climate change forces new species into communities, such as the movement of species from lower to higher latitudes or elevations.

“Species are expanding their ranges due to climate change, but what are the consequences to the existing structure and function of the ecosystem?” said Brad Taylor, professor of applied ecology at NC State and co-author of a paper describing the study. “Our study suggests that when resident and newcomer species are fairly similar, the consequences for ecosystem functions may not matter.”

The study examined a 30-year record of caddisfly populations in normally pristine ponds in Colorado, as well as some fundamental ecosystem functions that can be linked to an ecosystem’s health: the amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus excreted by the caddisflies and how fast dead plant material, or detritus, that enters ponds is processed by caddisflies. Resident and newcomer species can affect these processes in similar or different ways depending on who is in the community.

Shifts in nitrogen and phosphorus levels could lead to changes in the algal community, which is the food source that supports organisms higher up the food chain, such as fish or amphibians, Taylor said.

Meanwhile, caddisflies have an important role in detritus processing, as they consume decomposing wetland plant material and break it down into smaller pieces that can be consumed by other organisms. Taylor described an ecosystem with high detritus processing as one that is generally performing well.

The study reported three range expansions in caddisfly populations in the 30-year period; in the first two, caddisfly species similar in their processing of detritus and nutrients to resident caddisflies moved into the ponds. One similar newcomer species took a larger role in supplying nitrogen during the 30-year period.

Later, during the third expansion, one newcomer that was dissimilar to most resident species took over supplying phosphorus, but the overall processing of detritus and supply of nutrients in the ecosystem did not change despite these alterations in the community, Taylor said, and no evidence was found of declining caddisfly populations over time, although the dissimilar newcomer is on the verge of becoming the dominant resident.

“We have a unique temporal data set that documents the potential consequences of climate-induced introductions of species into new communities and ecosystems,” Taylor said. “A key part of predicting the potential effects of shifts in species is knowing the species-specific rates of nitrogen and phosphorus supply and the processing detritus.

“Nitrogen and phosphorus limit algae in these ponds, but how will changes in dominant species like caddisflies alter the abundance of these nutrients?” Taylor added. “What will be the change in the algal community when you get more phosphorus supply from a newcomer like the caddisfly we call nemo – short for the genus Nemotaulias – for example?”

Taylor and his collaborators intend to follow up on the long-term consequences of these expansions by examining their effects on other invertebrates and vertebrates given these changes.

“We know these range expansions are occurring and are going to continue occurring,” Taylor said. “We were able to measure three ecosystem processes in this study – there is still a lot more to explore.”

The study appears in Communications Biology. Corresponding author Jared Balik, a former Ph.D. student and postdoctoral researcher at NC State, Hamish Greig of the University of Maine-Orono and Scott Wissinger of Alleghany College are paper co-authors. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation under grants 1556914 and 1641041.

- kulikowski -

Note to editors: The paper abstract follows.

“Consequences of climate-induced range expansions on multiple ecosystem functions”

Authors: Jared A. Balik and Brad W. Taylor, NC State University; Hamish S. Greig, University of Maine, Orono; and Scott A. Wissinger, Alleghany College

Published: April 10, 2023 in Communications Biology

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-023-04673-w

Abstract: Climate-driven species range shifts and expansions are changing community composition, yet the functional consequences in natural systems are mostly unknown. By combining a 30-year survey of subalpine pond larval caddisfly assemblages with species-specific functional traits (nitrogen and phosphorus excretion, and detritus processing rates), we tested how three upslope range expansions affected species’ relative contributions to caddisfly-driven nutrient supply and detritus processing. A subdominant resident species (Ag. deflata) consistently made large relative contributions to caddisfly-driven nitrogen supply throughout all range expansions, thus “regulating” the caddisfly-driven nitrogen supply. Whereas, phosphorus supply and detritus processing were regulated by the dominant resident species (L. externus) until the third range expansion (by N. hostilis). Since the third range expansion, N. hostilis’s relative contribution to caddisfly-driven phosphorus supply increased, displacing L. externus’s role in regulating caddisfly-driven phosphorus supply. Meanwhile, detritus processing contributions became similar among the dominant resident, subdominant residents, and range expanding species. Total ecosystem process rates did not change throughout any of the range expansions. Thus, shifts in species’ relative functional roles may occur before shifts in total ecosystem process rates, and changes in species’ functional roles may stabilize processes in ecosystems undergoing change.

END

Abu Dhabi, UAE: – A team of scientists led by researchers at the University of Montreal has recently discovered an Earth-sized exoplanet, a world beyond our solar system, that may be carpeted with volcanoes and potentially hospitable to life. Called LP 791-18 d, the planet could undergo volcanic outbursts as often as Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanically active body in our solar system. The team includes Mohamad Ali-Dib, a research scientist at the NYU Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) Center for Astro, Particle, and Planetary Physics.

The planet was found and studied using data ...

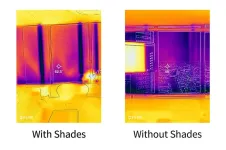

CHICAGO—May 17, 2023—Automated insulating window shades can cut energy consumption by approximately one-quarter and may recoup the cost of installation within three to five years, according to a landmark study conducted by Illinois Institute of Technology researchers at Willis Tower. The study, funded by ComEd, showcases a promising path for sustainability and energy efficiency in architectural design.

Temperature regulation typically accounts for 30–40 percent of the energy used by buildings in climates similar to Chicago. The research team, led by Assistant Professor of Architectural Engineering Mohammad ...

A large international team led by astronomers at the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets at Université de Montréal (UdeM) today announced in the journal Nature the discovery of a new temperate world around a nearby small star.

This planet, named LP 791-18 d, has a radius and a mass consistent with those of Earth. Observations of this exoplanet and another one in the same system indicate that LP 791-18 d is likely covered with volcanoes similar to Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanically active body in our Solar System.

“The discovery of this exoplanet is an extraordinary ...

A pair of internationally renowned stem cell cloning experts at the University of Houston is reporting their findings of variant cells in the lungs of patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) which likely represent key targets in any future therapy for the condition.

IPF is a progressive, irreversible and fatal lung disease in which the lungs become scarred and breathing becomes difficult. The rapid development and fatal progression of the disease occur by uncertain mechanisms, but the most pervasive school of thought is that IPF arises from recurrent, subclinical lung ...

For more than a century, biologists have wondered what the earliest animals were like when they first arose in the ancient oceans over half a billion years ago.

Searching among today's most primitive-looking animals for the earliest branch of the animal tree of life, scientists gradually narrowed the possibilities down to two groups: sponges, which spend their entire adult lives in one spot, filtering food from seawater; and comb jellies, voracious predators that oar their way through the world's oceans in search of food.

In a new study published this week in the journal Nature, researchers use a novel approach based on chromosome structure to come up with ...

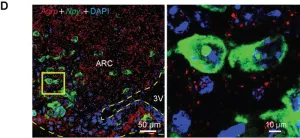

A team at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research has discovered a group of brain cells that boosts appetite when there is a prolonged surplus of energy in the body, such as excess fat accumulation in obesity.

The researchers discovered that these cells not only produced the appetite-stimulating molecule NPY, but they in fact made the brain more sensitive to the molecule, boosting appetite even more.

“These cells kickstart changes in the brain that make it more sensitive to even low levels of NPY when there is a surplus of energy in the body in the form of excess fat – driving appetite during obesity,” explains Professor Herbert Herzog, senior ...

About The Study: This study of 18.1 million beneficiaries of fee-for service Medicare found that, in contrast to in-person health services, receipt of medications for chronic conditions was relatively stable in the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic overall, across racial and ethnic groups, and for community-dwelling patients with dementia. This finding of stability may hold lessons for other outpatient services during the next pandemic.

Authors: Nancy E. Morden, M.D., M.P.H., of the Geisel ...

About The Study: This genetic association study including 39,000 participants with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer disease (AD) and 401,000 control participants without AD found novel genetic associations between high high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentrations and high systolic blood pressure with higher risk of AD. These findings may inspire new drug targeting and improved prevention implementation.

Authors: Ruth Frikke-Schmidt, M.D., D.M.Sc., Ph.D., of Copenhagen University Hospital–Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13734)

Editor’s ...

In the latest issue of the journal Nature, astronomers from Stockholm University reveal the origin of a thermonuclear supernova explosion. Strong emission lines of helium and the first detection of such a supernova in radio waves show that the exploding white dwarf star had a helium-rich companion.

Supernovae of Type Ia are important for astronomers since they are used to measure the expansion of the Universe. However, the origin of these explosions has remained an open question. While it is established that the explosion is that of a compact ...

Imagine an Earth-sized planet that’s not at all Earth-like. Half this world is locked in permanent daytime, the other half in permanent night, and it’s carpeted with active volcanoes. Astronomers have discovered that planet.

The planet, named LP 791-18d, orbits a small red dwarf star about 90 light years away. Volcanic activity makes the discovery particularly notable for astronomers because volcanism facilitates interaction between a world’s interior and its exterior.

“Why is volcanism important? It is the major source contributing to a planetary atmosphere, and with an atmosphere you could have surface liquid water — a requirement for sustaining ...