(Press-News.org) If you look at enough dinosaur fossils, you'll see that their skulls sport an amazing variety of bony ornaments, ranging from the horns of Triceratops and the mohawk-like crests of hadrosaurs to the bumps and knobs covering the head of Tyrannosaurus rex.

But paleontologists are increasingly finding evidence that dinosaurs had even more elaborate head ornaments not preserved with the fossil skulls — structures made of keratin, the stuff of fingernails, that were likely used as visual signals or semaphores to others of their kind.

A newly described species of dome-headed dinosaur — a pachycephalosaur dating from around 68 million years ago — is the latest example. Pachycephalosaurs lived during the Cretaceous period, between about 130 and 66 million years ago, and tended to be small-to-medium-sized plant eaters. Ranging from 3 to 15 feet long, they walked on two legs and had a long, stiff tail for balance.

The new species is based on a partial pachycephalosaur skull, including its bowling-ball shaped dome, that was unearthed in 2011 in the Hell Creek Formation in Montana, which are layers of Upper Cretaceous rock from which paleontologists have collected dinosaur fossils for decades.

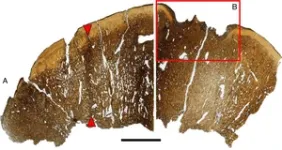

Based on CT scans and microscopic analyses of slices through the fossilized dome, paleontologists Mark Goodwin of the University of California, Berkeley, and John "Jack" Horner of Chapman University in Orange, California, concluded that the skull likely had sported bristles of keratin, reminiscent of a brush cut.

"We don't know the exact shape of what was covering the dome, but it had this vertical component that we interpret as covered with keratin," Goodwin said, noting that a bristly, flat-topped covering "biologically makes sense. Animals change or use certain features, particularly on the skull, for multiple functions — it could be for display or for social and biological interactions involving visual communication."

"I would guess that there was something pretty elaborate up there," said Horner, a lecturer and presidential fellow at Chapman, professor emeritus at Montana State University in Bozeman and emeritus curator at the Museum of the Rockies.

Peculiarly, the skull had a nasty gouge at the apex that had healed, indicating that a serious accident once befell the creature, but that it had survived long enough for new bone tissue to grow into the gash.

"We see probably the first unequivocal evidence of trauma in the head of any pachycephalosaur, where the bone was actually ejected from the dome somehow and healed partially in life," said Goodwin, emeritus assistant director and paleontologist at the UC Museum of Paleontology. "We don't know how that was caused. It could be head-butting — we don't dispute that."

Goodwin and Horner caution that this head lesion, about a half-inch deep, is not a smoking gun for the storied hypothesis that these dinosaurs butted heads as part of their social interactions — the Cretaceous equivalent of the way bighorn rams clash heads today. Instead, the injury could have been caused by anything from a falling rock to a chance encounter with a tree or another dinosaur.

"That's the first place everybody wants to go — let's crash them together. And, you know, we just don't see any evidence of it, histologically," Horner said, referring to detailed studies of the tissues underlying the dome, both in this specimen and in other pachycephalosaur skulls. "Something hit the top of this guy's head and damaged it, and it was something that was severe. But having a defense mechanism on your head is not a good idea, not for anybody. Any features, any accoutrements that we find on the heads of dinosaurs, I think, are all display — it's all about display."

Such ornamentation is common in the reptile ancestors of dinosaurs and their bird descendants; they're used both to attract mates and intimidate rivals. But Horner and Goodwin have long argued that the internal structure of pachycephalosaur skulls is not cushiony enough to allow head-butting without severe brain damage, and that head-butting is a mammal thing that is rarely seen in reptiles or birds. Specifically, pachycephalosaur skulls lack specializations, such as a pneumatic chamber above the braincase, as found in bighorn sheep, or other features present in mammals that engage in violent head-butting behavior.

"I don't see any reason to turn dinosaurs into mammals, rather than just trying to figure out what they might be doing as bird-like reptiles," Horner said.

Horner, Goodwin and David Evans of the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada published their description of the new pachycephalosaur last month in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. The team named the new species Platytholus clemensi, after the late UC Berkeley paleontologist William Clemens, who collected many fossils — in particular mammalian fossils — in the same Hell Creek Formation where the new species was found.

'A bowling ball in the fossil record'

According to Horner and Goodwin, pachycephalosaur skulls are quite common in many dinosaur beds, though somewhat less so in the Hell Creek Formation, which dates from the late Cretaceous Period, a few million years before the asteroid or comet impact that lowered the curtain on dinosaurs and changed the trajectory of life on Earth. One primary reason for the skulls’ ubiquity is the large bony dome.

"With pachycephalosaurs, think about a bowling ball in the fossil record," Goodwin said. "Their skulls roll around, get buried, and when exposed on the surface, they're very robust, so they can withstand a lot of weathering and erosion sitting out there. More than once, people have walked over an area all summer and discovered that what they thought was just a rock, because it looks like a glacial cobble, turned out to be a really nice dome."

Though Goodwin and Horner have unearthed many other fossils from the Hell Creek Formation over the past 45 to 50 years, including bones of Triceratops, T. rex and duckbilled hadrosaurs, they have a particular interest in pachycephalosaurs — both their evolution and their development from juvenile to adult. They've sliced through many skulls to study how they change over time and to test the theory that the creatures butted heads with one another, or at least, that the males did.

Their conclusion: There's no evidence, based on bone structure, that the skull or neck could withstand a head-to-head collision. The newly described partial skull, which was not found with other parts of the skeleton, also has a bone structure inconsistent with head-butting.

Because the skull bones didn't look like specimens from any of the other two types of juvenile, sub-adult or adult pachycephalosaurs that lived in the area around the same time — Pachycephalosaurus itself, after which these dinosaurs are named, and Sphaerotholus — the paleontologists classified the animal as a new genus and species, Platytholus clemensi.

The skull did have characteristics that the paleontologists had seen in other pachycephalosaurs, including Sphaerotholus: blood vessels in the skull that ended abruptly at the surface of the dome, indicating that the blood originally fed some tissue that was sitting atop the dome. If that covering were a sheath of keratin, the blood vessels would have spread out and left indentations or grooves along the domed surface, as seen, for example, under the beaks of birds or on the skulls of Triceratops and other ceratopsians or horned dinosaurs. But the vessels were perpendicular to the surface, as if they fed a vertical structure.

"What we see are these vertical canals coming to the surface, which suggests that there might be keratin on top, but it's oriented vertically," said Horner. "I think these pachycephalosaurs had something on top of their head that we don't know about. I don't think they were just domes. I think there was some elaborate display on top of their head."

Goodwin noted that the shape of the domed heads of pachycephalosaurs changed as the animals matured, becoming more prominent and elaborate as they approached adulthood. That, too, would suggest they were used for sexual display and courting, though they may have been used to butt the flanks, as opposed to the heads, of male rivals. He suspects that dinosaurs likely distinguished gender by color, as do most modern birds, such as cassowaries, peafowls and toucans, which have bright integumental colors around the face and head for visual communication.

"It’s reasonable to suggest that the covering over the dome may also have been brightly colored or subject to color change seasonally," he said.

The paleontologists are obtaining CT scans and doing thin-section histology of other pachycephalosaur domes to determine whether other dome-headed dinosaurs may have displayed elaborate vertical headgear in addition to the known array of bumps, nodes and horns.

"The combination of cranial histology after thin-sectioning the skull and CT scanning gave us a much richer body of data and forms a basis for our hypothesis that there was a keratinous covering over the dome," Goodwin said. "We know the dome was covered with something, and we make a hypothesis, at least in this taxon, that it had a vertical structural component, unlike Triceratops, T. rex and other dinosaurs, which had hard skin or keratin closely covering the bone.”

Goodwin and Horner named the new species after Clemens because both developed close ties to him over the many summers all three explored Montana in search of Cretaceous fossils, sometimes working side by side in the field.

"Bill Clemens was a very important person in Mark's life, but he may have been more important in my life because he was the person who, back in 1978, said, 'You know, Jack, there's this woman in Bynum, Montana, who found a large dinosaur, and she needs it identified,'" Horner said. When he and colleague Bob Makela checked out the woman's rock shop, Horner said, she asked about a few smaller fossils in her shop, too, which turned out to be "the first baby dinosaur bones found in the world."

That discovery provided the first clear evidence that some dinosaurs cared for their young and led Horner to write several books about family structure among duckbilled dinosaurs, including Digging Dinosaurs in 1988 and a sequel, Dinosaur Lives: Unearthing an Evolutionary Saga, in 1997. He also wrote several children's books, including Maia: A Dinosaur Grows Up, in 1995, about a baby duckbill of the species Horner named Maiasaura, and the 2023 sequel, Lily and Maia....a Dinosaur Adventure.

"I owe a great amount of gratitude to Bill Clemens for sending me on that little trip," said Horner.

The work was funded by a Smithsonian Institution grant to Horner and grants from the National Science Foundation (EAR-1053370) to Goodwin.

END

Did dome-headed dinosaurs sport bristly headgear?

CT scans suggest some pachycephalosaurs had elaborate structures atop their domes

2023-05-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Lupus Research Alliance and its clinical research affiliate Lupus Therapeutics launch the Lupus Landmark Study to accelerate personalized treatments in lupus

2023-05-23

NEW YORK, NY (May 23) – The Lupus Research Alliance and its clinical research affiliate Lupus Therapeutics today announced the launch of the Lupus Landmark Study, a groundbreaking observational research study to accelerate the development of personalized treatments for people living with lupus. The Lupus Landmark Study, the largest study of its kind in lupus, will prospectively recruit and longitudinally follow 3,500 adults diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The Lupus Landmark Study is a ...

The severity of sleep apnea may be underestimated in Black patients

2023-05-23

Session: C110, Advanced Signal Analysis: New Diagnostics and Physiologic Insights for SDB (sleep-disordered breathing)

Date and Time: 2:15 p.m. ET, Tuesday, May 23, 2023

Location: WEWCC, Room 144 A-C (Street Level)

ATS 2023, Washington, DC – Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) tests may underestimate the severity of OSA in Black patients, according to research published at the ATS 2023 International Conference.

Recent research with ICU patients during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that pulse oximeters—clip-like devices that are attached to a fingertip to measure blood oxygen ...

Strategic city planning can help reduce urban heat island effect

2023-05-23

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — The tendency of cities to trap heat — a phenomenon called the “urban heat island,” often referred to as the UHI effect — can lead to dangerous temperatures in the summer months, but new Penn State research suggests that certain urban factors can reduce this effect.

The study found that trees had a cooling effect on outdoor air temperature, mean radiant temperature and predicted mean vote index, a measurement designed to evaluate thermal comfort levels.

Additionally, the researchers determined that higher building-height-to-street-width ratios — when taller ...

The aging mouse prostate: kinetics of lymphocyte infiltration

2023-05-23

“This dataset presents the most comprehensive profiling of the aging adult mouse prostate immune profile to date.”

BUFFALO, NY- May 23, 2023 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 15, Issue 9, entitled, “Highly multiplexed immune profiling throughout adulthood reveals kinetics of lymphocyte infiltration in the aging mouse prostate.”

Aging is a significant risk factor for disease in several tissues, including the prostate. Defining the kinetics ...

Organizations must go beyond medical views on menopause to support women’s professional aspirations - study

2023-05-23

Organisations must enable mid-life women to thrive in the workplace by taking inspiration from societies such as China and Japan to encourage positive conversations around the impact of menopause, a new study reveals.

But as they support older women in pursuing their ambitions and accessing career opportunities, organisations must ensure they do not hinder career progression through overlooked promotions, undervalued work, and lost opportunities.

In Western countries, the menopause is traditionally viewed as a managed medical condition that creates physiological challenges which women must overcome if they are to function as effectively in the workplace ...

Insomnia drug class may not influence death and exacerbation risks among patients with COPD

2023-05-23

Session: C98, Risky Business: Predicting Consequences of OSA

Date and Time: 2:51 p.m. ET, Tuesday, May 23, 2023

Location: Marriott Marquis Washington, Independence Ballroom, Salons E-H (Level M4)

ATS 2023, Washington, DC – Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients newly prescribed non-benzodiazepine benzodiazepine receptor agonists (NBZRAs) such as zolpidem (Ambien, Intermezzo and other brands), a class of hypnotic drugs prescribed for insomnia, did not have an increased risk of exacerbations requiring hospitalizations or of death than those prescribed ...

Researchers treat depression by reversing brain signals traveling the wrong way

2023-05-23

Powerful magnetic pulses applied to the scalp to stimulate the brain can bring fast relief to many severely depressed patients for whom standard treatments have failed. Yet it’s been a mystery exactly how transcranial magnetic stimulation, as the treatment is known, changes the brain to dissipate depression. Now, research led by Stanford Medicine scientists has found that the treatment works by reversing the direction of abnormal brain signals.

The findings also suggest that backward streams of neural activity between key areas of the brain could be used as a biomarker to help diagnose depression.

“The leading ...

Strategic habitat restoration can generate a win-win for forests and farmers

2023-05-23

Carefully planned restoration of agricultural coffee landscapes can increase both farmers’ profit and forest cover over a 40-year period, according to a study publishing May 23rd in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Dr. Sofía López-Cubillos at the University of Queensland in Australia, and colleagues.

Restoring patches of natural vegetation in agricultural land presents a trade-off for farmers: while the lost cropland can reduce profitability, increases in ecosystem services like pollination can improve crop yield. To investigate how conservation priorities can be balanced with economic needs, researchers developed a novel planning framework to model the ...

Oxygen restriction helps fast-aging mice live longer

2023-05-23

For the first time, researchers have shown that reduced oxygen intake, or “oxygen restriction”, is associated with longer lifespan in lab mice, highlighting its anti-aging potential. Robert Rogers of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, US, and colleagues present these findings in a study publishing May 23rd in the open access journal PLOS Biology.

Research efforts to extend healthy lifespan have identified a number of chemical compounds and other interventions that show promising effects in mammalian lab animals— ...

How the February 2023 Türkiye earthquakes ruptured and produced damaging shaking

2023-05-23

Three studies now published in the open-access journal The Seismic Record offer an initial look at the February 6, 2023 earthquakes in south-central Türkiye and northwestern Syria, including how, where, and how fast the earthquakes ruptured and how they combined as a “devastating doublet” to produce damaging ground shaking.

The two earthquakes, a magnitude 7.8 followed approximately nine hours later by a magnitude 7.6, took place at the tectonically active and complex junction between the Anatolian, Arabian, and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

New study clarifies how temperature shapes sex development in leopard gecko

Major discovery sparks chain reactions in medicine, recyclable plastics - and more

Microbial clues uncover how wild songbirds respond to stress

Researchers develop AI tools for early detection of intimate partner violence

Researchers develop AI tool to predict patients at risk of intimate partner violence

New research outlines pathway to achieve high well-being and a safe climate without economic growth

How an alga makes the most of dim light

Race against time to save Alpine ice cores recording medieval mining, fires, and volcanoes

Inside the light: How invisible electric fields drive device luminescence

A folding magnetic soft sheet robot: Enabling precise targeted drug delivery via real-time reconfigurable magnetization

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for March 2026

New tools and techniques accelerate gallium oxide as next-generation power semiconductor

Researchers discover seven different types of tension

Report calls for AI toy safety standards to protect young children

VR could reduce anxiety for people undergoing medical procedures

Scan that makes prostate cancer cells glow could cut need for biopsies

Mechanochemically modified biochar creates sustainable water repellent coating and powerful oil adsorbent

New study reveals hidden role of larger pores in biochar carbon capture

Specialist resource centres linked to stronger sense of belonging and attainment for autistic pupils – but relationships matter most

Marshall University, Intermed Labs announce new neurosurgical innovation to advance deep brain stimulation technology

Preclinical study reveals new cream may prevent or slow growth of some common skin cancers

Stanley Family Foundation renews commitment to accelerate psychiatric research at Broad Institute

What happens when patients stop taking GLP-1 drugs? New Cleveland Clinic study reveals real world insights

American Meteorological Society responds to NSF regarding the future of NCAR

Beneath Great Salt Lake playa: Scientists uncover patchwork of fresh and salty groundwater

Fall prevention clinics for older adults provide a strong return on investment

People's opinions can shape how negative experiences feel

USC study reveals differences in early Alzheimer’s brain markers across diverse populations

300 million years of hidden genetic instructions shaping plant evolution revealed

[Press-News.org] Did dome-headed dinosaurs sport bristly headgear?CT scans suggest some pachycephalosaurs had elaborate structures atop their domes