(Press-News.org) Coccolithophores, a globally ubiquitous type of phytoplankton, play an essential role in the cycling of carbon between the ocean and atmosphere. New research from Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences shows that these vital microbes can survive in low-light conditions by taking up dissolved organic forms of carbon, forcing researchers to reconsider the processes that drive carbon cycling in the ocean. The findings were published this week in Science Advances.

The ability to extract carbon from the direct absorption of dissolved organic carbon is known as osmotrophy. Though scientists had previously observed osmotrophy by coccolithophores using lab-grown cultures, this is the first evidence of this phenomenon in nature.

The team, led by Senior Research Scientist William Balch, undertook their experiments in populations of coccolithophores across the northwest Atlantic Ocean. They measured the rate at which phytoplankton fed on three different organic compounds, each labeled with chemical markers to track them. The dissolved compounds were used by the coccolithophores as a carbon source for both the organic tissues that comprise their single cells as well as the inorganic mineral plates, called coccoliths, which they secrete around themselves. Uptake of the organic compounds was slow compared to the rate at which phytoplankton can take up carbon through photosynthesis. But it wasn’t negligible.

“The coccolithophores aren’t winning any ‘growth race’ by taking-up these dissolved organic materials,” Balch said. “They are just eking out an existence, but they can still grow, albeit slowly.”

Plants, like coccolithophores, typically acquire their carbon for growth from inorganic forms of carbon extracted from the atmosphere like carbon dioxide and bicarbonate through photosynthesis. When coccolithophores die, they sink, carrying all that carbon down to the ocean floor where it can be remineralized or buried, effectively sequestering it for millions of years. This process is called the biological carbon pump.

As part of a parallel process called the alkalinity pump, coccolithophores also convert bicarbonate molecules in surface water into calcium carbonate — essentially limestone — that forms their protective coccoliths. Again, when they die and sink, all that dense inorganic carbon is ballasted to the seafloor. Some of it then dissolves back into bicarbonate, thus ‘pumping’ alkalinity from the surface to depth.

But the new evidence suggests that coccolithophores aren’t just using these inorganic forms of carbon near the surface. They’re also taking up dissolved organic carbon, the largest pool of organic carbon in the sea, and fixing some of it into their coccoliths, which ultimately sink into the deep ocean. This suggests that the uptake of these free-floating organic compounds is another step in both the biological and alkalinity pumps that drive the transport of carbon from the ocean surface to depths below.

“There’s this big dissolved organic carbon source in the ocean that we always assumed wasn’t really related to the carbonate cycle in the sea,” Balch said. “Now we’re saying that some fraction of the carbon that is going to depth is really coming from that enormous pool of dissolved organic carbon.”

This is the third and final paper published as part of a three-year National Science Foundation-funded project. The overall effort was inspired by a decades-old dissertation by William Blankley, a graduate student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Balch’s alma mater. In the 1960s, Blankley was able to grow coccolithophores in the dark for 60 days feeding them glycerol, one of the organic compounds used in the present study. Unfortunately, he died before his research could be published. The fact that Blankley’s findings could be reproduced all these years later with new technology, Balch said, is credit to the quality of that early work.

The real challenge of the most recent study, though, was to undertake that research outside of a controlled lab environment. The team had to devise a method to measure these organic compounds in seawater — at ambient concentrations orders of magnitude lower than the Blankley experiments — and then track how they were being taken up by wild coccolithophores.

“When you culture phytoplankton in the lab, you can grow as much as you want. But in the ocean, you take what you get,” Balch said. “The challenge was finding a signal in all the noise to say, proof positive, that it was coccolithophores taking up these organic molecules into their coccoliths.”

Though the current project is complete, Balch said the next step is to examine whether coccolithophores are able to take up other organic compounds found in seawater at the same rate as the three tested thus far. Though the coccolithophores were using the three dissolved compounds at slow rates in these experiments, there are thousands of other organic molecules in seawater that they could potentially absorb. If they are using more of them, this finding may prove to be an even more significant step in understanding the global carbon cycle.

Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences is an independent, nonprofit research institute located in East Boothbay, Maine. From the Arctic to the Antarctic, Bigelow Laboratory scientists use innovative approaches to study the foundation of global ocean health and unlock its potential to improve the future for all life on the planet. Learn more at bigelow.org, and join the conversation on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

END

Scientists provide first field observations of coccolithophore osmotrophy

2023-05-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Not so biodegradable: new study finds bio-based plastic and plastic-blend textiles do not biodegrade in the ocean

2023-05-24

Plastic pollution is seemingly omnipresent in society, and while plastic bags, cups, and bottles may first come to mind, plastics are also increasingly used to make clothing, rugs, and other textiles.

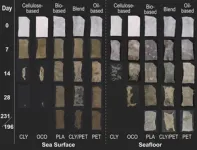

A new study from UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, published May 24 in the journal PLOS One, for the first time tracked the ability of natural, synthetic, and blended fabrics to biodegrade directly in the ocean.

Lead author Sarah-Jeanne Royer conducted an experiment off the Ellen Browning Scripps Memorial Pier and found that natural and wood-based cellulose fabrics degraded within a month. Synthetic textiles, including so-called compostable ...

Increasing heat likely a major factor in human migration

2023-05-24

Rising temperatures due to climate change are likely influencing human migration patterns, according to a new study by Rita Issa of University College London and colleagues, published May 24 in the open-access journal PLOS Climate.

In the last decade, heatwaves were frequent, and surface temperatures were the warmest on record. As the planet warms, many people are expected to leave their homes to escape extreme temperatures. However, the exact role of heat in human migration is not yet understood. To illuminate this relationship, Issa’s team conducted a review of research documents, ...

Public health solutions to disrupt the US firearm crisis

2023-05-24

The epidemic of firearm injury and death in the USA is preventable, and the field of public health can offer practical solutions, argue Dr. Megan L. Ranney and colleagues in an opinion article in PLOS Global Public Health. Through harm reduction and community engagement programs, public health professionals, healthcare providers and community members can reduce the impact on individuals, families and communities.

Despite the attention school and public mass shootings in the US gain, they make up a minority of US firearm injuries and deaths. Most firearm deaths are from homicide and suicide: ...

Gender trumps politics in determining people’s ability to read others’ minds

2023-05-24

Political parties regularly claim to have their finger on the pulse and be able to read the public mood. Yet a new study challenges the idea that being political makes you good at understanding others: it shows gender, not politics, is a far more important factor in determining people’s social skills.

Analysis of a sample of 4,000 people from across the UK, compiled by a team of psychologists at the University of Bath, highlights that being female and educated are the biggest determinants of whether you can understand or read others’ ...

Georgia Tech researchers develop wireless monitoring patch system to detect sleep apnea at home

2023-05-24

The prevalence of sleep disorders, like sleep apnea, is on the rise in the U.S., but current protocols to conduct clinically accepted assessments are expensive and inconvenient.

Georgia Tech researchers have created a wearable device to accurately measure obstructive sleep apnea — when the body repeatedly stops and restarts breathing for a period — as well as the quality of sleep people get when they are at rest.

Under conventional methods, people who are suspected of having some sleep issue or disorder ...

How tasty is the food?

2023-05-24

To know when it’s time for a meal – and when to stop eating again – is important to survive and to stay healthy, for humans and animals alike. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence investigated how the brain regulates feeding behavior in mice. The team found that the hormone ghrelin activates specialized nerve cells in a brain region known as the amygdala. Here, the interaction between ghrelin and the specialized neurons promotes food consumption and conveys ...

Discovery slows down muscular dystrophy

2023-05-24

A team of researchers at the University of Houston College of Pharmacy is reporting that by manipulating TAK1, a signaling protein that plays an important role in development of the immune system, they can slow down disease progression and improve muscle function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

DMD, caused by mutations in dystrophin gene, is an inheritable neuromuscular disorder that occurs in one out of 3,600 male births. DMD patients undergo severe muscle wasting, inability to walk and eventually death in their early thirties due to respiratory failure. The ...

A novel method to quantify individual limb contributions to standing postural control

2023-05-24

Research question

Can these contributions to standing postural control be quantified from CoP trajectories in neurotypical adults?

Methods

Instantaneous contributions can be negative or larger than one, and integrated contributions sum to equal one. Proof-of-concept demonstrations validated these calculated contributions by restricting CoP motion under one or both feet. We evaluated these contributions in 30 neurotypical young adults who completed two (eyes opened; eyes closed) 30-s trials of bipedal standing. We evaluated the relationships between limb contributions, self-reported limb dominance, and between-limb ...

NASA data could lead to more accurate weather forecasts

2023-05-24

A University of Texas at Arlington civil engineering researcher will use a NASA grant to help forecasters better predict extreme weather events using a variety of existing NASA data sources.

Yu Zhang, associate professor in the Department of Civil Engineering, said the $638,000 grant will use ocean circulation data, atmospheric conditions and current weather information to make longer-range forecasting more reliable. Having a more accurate forecast could help officials make better decisions about the state’s water resources—for example, knowing when to release water from reservoirs.

“Using ...

Digital engineering to reduce risks that lead to brain injuries

2023-05-24

A University of Texas at Arlington engineering researcher who studies traumatic brain injuries has received funding to use computer motion simulation that replicates the movements of a person performing activities that could lead to injury.

The project, funded by a nearly $1 million grant from the Office of Naval Research Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (DURIP), will use real-time data of phantom head and phantom body reactions to ascertain what physical injuries could come from those motions.

Ashfaq Adnan, a UT Arlington professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, is leading the project, called “System for Remote ...