(Press-News.org) An international team of researchers, led by University of Toronto Engineering Professor Yu Zou, is using electric fields to control the motion of material defects. This work has important implications for improving the properties and manufacturing processes of typically brittle ionic and covalent crystals, including semiconductors — a crystalline material that is a central component of electronic chips used for computers and other modern devices.

In a new study published in Nature Materials, researchers from University of Toronto Engineering, Dalhousie University, Iowa State University and Peking University, present real-time observations of dislocation motion in a single-crystalline zinc sulfide that was controlled using an external electric field.

“This research opens the possibility of regulating dislocation-related properties, such as mechanical, electrical, thermal and phase-transition properties, through using an electric field, rather than conventional methods” says PhD candidate Mingqiang Li, the first author of the new paper.

In materials science, dislocation is a linear crystallographic defect within a crystal structure that contains an abrupt change in the arrangement of atoms.

It is the most important defect in crystalline materials, says Zou, since it can affect the strength, ductility, toughness, thermal and electrical conductivities of crystalline materials, such as steel used in airplanes and silicon used in chips.

In crystalline solids, good ductility and formability are generally achieved by dislocation movement. As such, metals that have highly mobile dislocations can be deformed into final products through compression, tension, rolling and forging — for example, aluminum cans are punched out to form the shape.

In contrast, ionic and covalent crystals generally suffer from poor dislocation mobility that make them too brittle to process using mechanical methods, and as a result, unsuited to a broad range of manufacturing techniques. In the case of semiconductors, they are typically too brittle to be rolled and forged.

“The primary driving force of dislocation motion has been commonly limited to mechanical stress, restricting the processing routes and engineering applications of many brittle crystalline materials,” says Zou.

“Our study provides direct evidence of dislocation dynamics controlled by a non-mechanical stimulus, which has been an open question since the 1960s. We also rule out other effects on the dislocation motion, including Joule heating, electron wind force and electron beam irradiation.”

The study used an in-situ transmission electron microscopy to observe dislocation motion in zinc sulfide, which was driven solely by an applied electric field in the absence of mechanical loading. Dislocations that carried negative or positive charges were both triggered by the electric field.

The researchers observed dislocations moving back and forth while changing the direction of the electric field. They also found that the mobilities of dislocations in an electric field also depends on their dislocation types.

Since most semiconductors are brittle due to their poor dislocation mobility, the electric-field-controlled dislocation motion in this new study may be used to enhance their mechanical reliability and formability, says Li.

“In addition, our work offers an alternative method to reduce defect density in semiconductors, insulators and aged devices that doesn’t require traditionaltedious thermal annealing, which uses temperature over time to reduce defects of a material,” he adds.

While this initial study has been focused on zinc sulfide, the team is planning to explore a wide range of materials, from covalent crystals to ionic crystals.

“As we work towards the application of this technology, our aim is to collaborate with the materials and manufacturing industries, particularly semiconductor companies, to develop a new manufacturing process to reduce defect density and improve the properties and performance of semiconductors,” says Zou.

END

University of Toronto Engineering researchers are using electric fields to control the movement of defects in crystals

New phenomenon of controlling dislocation motion has the potential to improve performance and formability of semiconductors and other brittle crystalline materials

2023-06-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Assessment of a peer support group intervention for undocumented Latinx immigrants with kidney failure

2023-06-21

About The Study: This study of 23 undocumented immigrants with kidney failure receiving emergency dialysis found that a peer support group intervention achieved feasibility and acceptability. The findings suggest that a peer support group may be a patient-centered strategy to build camaraderie and provide emotional support in kidney failure, especially for socially marginalized uninsured populations who report limited English proficiency.

Authors: Lilia Cervantes, M.D., of the University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, in Aurora, is the corresponding author.

To ...

Biodegradable gel shows promise for cartilage regeneration

2023-06-21

A gel that combines both stiffness and toughness is a step forward in the bid to create biodegradable implants for joint injuries, according to new UBC research.

Mimicking articular cartilage, found in our knee and hip joints, is challenging. This cartilage is key to smooth joint movement, and damage to it can cause pain, reduce function, and lead to arthritis. One potential solution is to implant artificial scaffolds made of proteins that help the cartilage regenerate itself as the scaffold biodegrades. How well the cartilage regenerates is linked to how well a scaffold can mimic the biological properties of cartilage, and to date, researchers have struggled ...

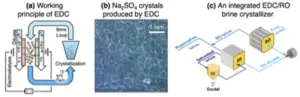

New study in Nature Water demonstrates a vastly more sustainable, cost-effective method to desalinate industrial wastewater

2023-06-21

Vanderbilt researchers are part of a team that has developed a cutting-edge method that seeks to make the removal of salt from hypersaline industrial wastewater far more energy-efficient and cost-effective.

While desalination through reverse osmosis has made tremendous strides—allowing for salt removal from seawater for less than a penny per gallon—it still falls short in eliminating saline in wastewater from industries like mining, oil and gas and power generation and in inland brackish water. The industrial brines are currently injected into deep geological formations or transferred to a evaporation ponds, and both disposal methods are facing more regulatory and ...

Researchers reveal mechanism of protection against breast and ovarian cancer

2023-06-21

In a new paper published today in Nature, researchers at the Francis Crick Institute have outlined the structure and function of a protein complex which is required to repair damaged DNA and protect against cancer.

Every time a cell replicates, mistakes can happen in the form of mutations, but specialised proteins exist to repair the damaged DNA.

People with mutations in a DNA repair protein called BRCA2 are predisposed to breast, ovarian and prostate cancers, which often develop at a young age. In the clinic, these cancers are treated with a drug that inhibits PARP, ...

Atoms realize a Laughlin state

2023-06-21

The discovery of the quantum Hall effects in the 1980's revealed the existence of novel states of matter called "Laughlin states", in honor of the American Nobel prize winner who successfully characterized them theoretically. These exotic states specifically emerge in 2D materials, at very low temperature and in the presence of an extremely strong magnetic field. In a Laughlin state, electrons form a peculiar liquid, where each electron dances around its congeners while avoiding them as much as possible. Exciting such a quantum liquid generates collective states that physicists associate to fictitious particles, whose ...

Ovarian cancer study identifies key genes for potential treatments

2023-06-21

New research is increasing our understanding about why some women with the most lethal form of ovarian cancer respond much better to treatment than others.

Researchers at Imperial College London have confirmed that the tumours of some women with high-grade serious ovarian cancer (HGSOC) contain a type of lymphoid tissue – known as tertiary lymphoid structures, or TLS – and that the presence of this tissue gives women a significantly better prognosis. They have also identified genes in HGSOC ...

Detection of an echo emitted by our Galaxy's black hole 200 years ago

2023-06-21

An international team of scientists has discovered that Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*)1, the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way, emerged from a long period of dormancy some 200 years ago. The team, led by Frédéric Marin2, a CNRS researcher at the Astronomical Strasbourg Observatory (CNRS/University of Strasbourg), has revealed the past awakening of this gigantic object, which is four million times more massive than the Sun. Their work is published in Nature on 21 June. Over a period of one year at the beginning of the 19th century, the black ...

Study hints at how cancer immunotherapy can be safer

2023-06-21

New Haven, Conn. — Cancer immunotherapy has revolutionized treatment of many forms of cancer by unleashing the immune system response against tumors. Immunotherapies that block checkpoint receptors like PD-1, proteins that limit the capacity of T cells to attack tumors, have become the choice for the treatment of numerous types of solid cancer.

However, the introduction of PD-1-blocking agents can often result in T cells attacking healthy tissues in addition to cancer cells, causing severe, sometimes life-threatening, side effects that can blunt the benefits of immunotherapy.

A new study published by researchers ...

Drug-resistant fungi are thriving in even the most remote regions of Earth

2023-06-21

New McMaster research has found that a disease-causing fungus — collected from one of the most remote regions in the world — is resistant to a common antifungal medicine used to treat infections.

The study, published today in mSphere, showed that seven per cent of Aspergillus fumigatus samples collected from the Three Parallel Rivers region in Yunnan, China were drug resistant.

Perched 6,000 metres above sea level and guarded by the staggering glaciated peaks of the Eastern Himalayas, the region is sparsely populated and undeveloped, which makes the presence of antimicrobial-resistant strains of A. fumigatus all the more striking for Jianping Xu, ...

Direct photons point to positive gluon polarization

2023-06-21

UPTON, NY— A new publication by the PHENIX Collaboration at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) provides definitive evidence that gluon “spins” are aligned in the same direction as the spin of the proton they’re in. The result, just published in Physical Review Letters, provides theorists with new input for calculating how much gluons—the gluelike particles that hold quarks together within protons and neutrons—contribute to a proton’s ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

New study clarifies how temperature shapes sex development in leopard gecko

[Press-News.org] University of Toronto Engineering researchers are using electric fields to control the movement of defects in crystalsNew phenomenon of controlling dislocation motion has the potential to improve performance and formability of semiconductors and other brittle crystalline materials